The seven kinds of friendships you find in literature: a taxonomy.

In a 2016 review of Dana Spiotta’s Innocents and Others, the novelist Joshua Cohen boldly declared, “There is no such thing as the Friendship Plot, because while friendship, like marriage, is at least presumably a voluntary estate, it has no official consummation.” Though Cohen made this case well before we got to feast on this nailbiter—or this one—there’s something to this point. Either by design or imaginative failure, great romance has historically trumped great friendship, as a literary subject.

I often wonder why this should be. As Cohen implies, the lonesome protagonist commonly found in contemporary fiction may serve a craft function. Without a sounding board to point out their unreasonable behaviors, a character can avoid the hijinks that the juiciest novels are made of. But when the “unconsummated” estate is present and plausible, I fall in love easier. The best friendships in fiction really do stick to your ribs.

So, what could the Friendship Plot look like? To the end of brainstorming a canon, let’s start with a taxonomy. Here are the seven kinds of friendships you’ll find in a novel.

Ruth Negga and Tessa Thompson in Rebecca Hall’s adaptation of Passing.

Ruth Negga and Tessa Thompson in Rebecca Hall’s adaptation of Passing.

The Repelling Magnets

Sometimes called the frenemy, these kinds of friends are constantly at war. But a mutual fascination keeps them in competitive orbit. They take turns judging and marveling at the other, and the quieter one may go on to write a book about the other someday. Ur-examples include Nel and Sula, and Lila and Lenu of The Neapolitan Novels.

See also: Clare and Irene, of Passing. Georgette and Ann of Sigrid Nunez’s The Last of Her Kind. Berie and Sils of Who Will Run the Frog Hospital?

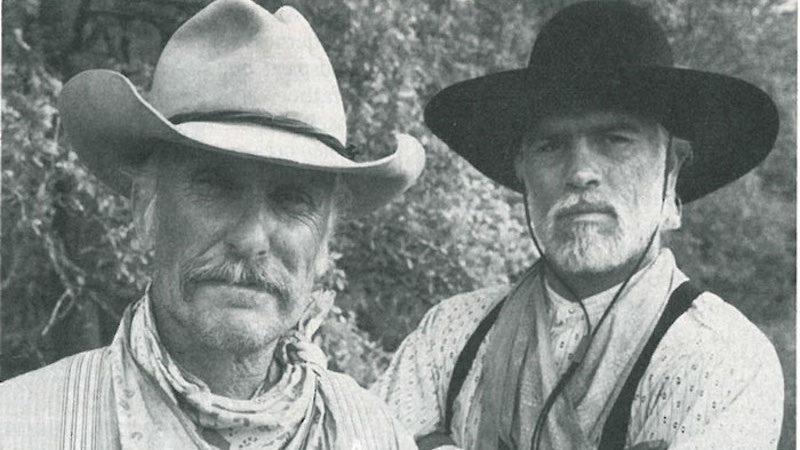

Robert Duvall and Tommy Lee Jones in Peter Bogdanovich’s spin on Lonesome Dove.

Robert Duvall and Tommy Lee Jones in Peter Bogdanovich’s spin on Lonesome Dove.

The Ride or Dies

In this pairing, equilibrium relies on the tacit acknowledgment that one person is Alpha. But unlike the frenemy, this friendship is built to withstand upheaval. When Charlotte gets that manse of her own, Lizzie swallows her pride and comes correct to Casa Collins. Likewise, Frances and Bobbi, of Conversations with Friends, can push through all kinds of tension thanks to their mutual knack for—you guessed it—chat.

See also: Gus and Call, of Larry McMurtry’s Lonesome Dove. Christina and Frieda of Two Serious Ladies. Agnes and Polly of Fellowship Point.

The theater troupe in HBO’s Station Eleven.

The theater troupe in HBO’s Station Eleven.

The Intentional Flock

This kind of friendship forms around a project or common cause. Typically that cause is artistic or political. The gang of eco-warriors at the heart of Eleanor Catton’s Birnam Wood come to mind. Or Dana Spiotta’s New Left cell in Eat the Document.

See also: the surviving and thriving theatre troupe at the heart of Emily St. John Mandel’s Station Eleven. Or the work-hard-play-hard trifecta in Gabrielle Zeavin’s Tomorrow, and Tomorrow, and Tomorrow.

Sydney Lumet’s vision of The Group, from the 1966 film.

Sydney Lumet’s vision of The Group, from the 1966 film.

The Circumstantial Flock

One of my favorite categories of book can be short-handed as “four friends in the city.” This kind of novel—or series, in Armistead Maupin’s case—follows a cohort over years of transformation. As the world turns, entanglements deepen or fall away. Not that much else has to happen, frankly. Perhaps in this category, we find the rumblings of a Friendship Plot.

We can trace the circumstantial flock from Mary McCarthy’s The Group to Meg Wolitzer’s The Interestings to Lisa Ko’s Memory Piece. A recent favorite in this category is Gary Indiana’s Do Everything in the Dark.

See also: Emma Copley Eisenberg’s Housemates, Armistead Maupin’s Tales of the City, Hanya Yanagihara’s A Little Life.Terry McMillan’s Waiting to Exhale.

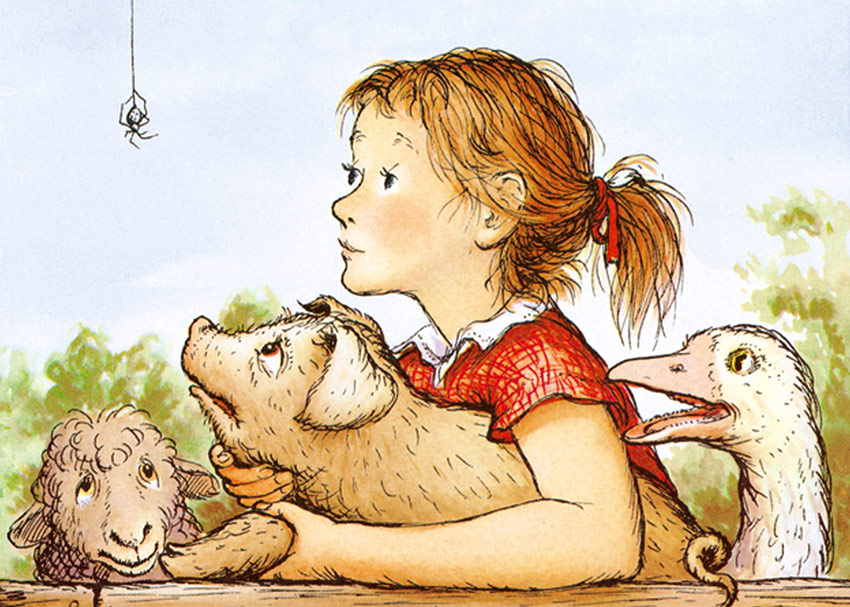

Several species of friendship in Charlotte’s Web.

Several species of friendship in Charlotte’s Web.

Interspecies Pals

Because “unlikely” deserves breaking down, and because we all know who (wo)man’s best friend really is. Sigrid Nunez is the reigning bard of this category. Her novels The Friend and The Vulnerables depict women in thrall to a Great Dane and a parrot, respectively. For a thornier depiction of the human-animal connection, consider the adopted chimp in Kaitlyn Greenidge’s We Love You, Charlie Freeman.

See also: E.B. White’s Charlotte’s Web. Not to mention the great canon of horse girl literature.

My favorite intergenerational friendship.

My favorite intergenerational friendship.

Intergenerational Pals

The friendship that collapses decades can also be great for drama. Contrasting POVs engender sharp contrast, and there’s sometimes a frisson of illicit romance when these kinds of far-flung stars cross. Consider how Tsukiko of Hiromi Kawakami’s Strange Weather in Tokyo is rocked when she stumbles across her old Sensei.

See also: There’s a wonderfully complex connection between William Beckwith and Lord Nantwich in Alan Hollinghurst’s The Swimming Pool Library. And in sillier news, Tolkien’s Lord of the Rings.

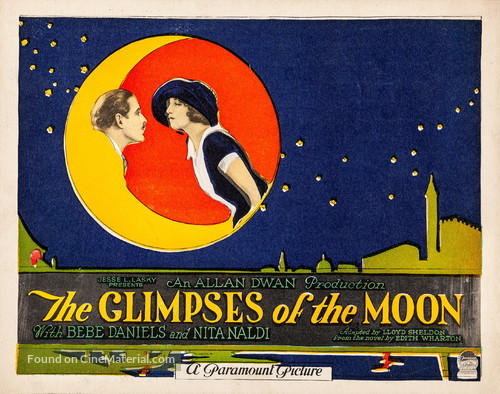

Poster from the lost 1923 film adaptation.

Poster from the lost 1923 film adaptation.

The I-Don’t-Wanna-Be-Friends-Friends

This one is a slippery category. Sometimes, the I-don’t-wanna-be-friends-friends are pressed into alliance for heist-purposes. Like the scheming social climbers in Edith Wharton’s Glimpses of the Moon.

Other times, this kind of friendship sprouts from the reverse impulse. Two people set out to be friends, but then one gets a crush. That crush then turns sour turn when it comes to light that one person is missing key parts of a soul.

See also: Fay and Nell of James Frankie Thomas’ Idlewild. Selin and Ivan, of The Idiot.

Brittany Allen

Brittany K. Allen is a writer and actor living in Brooklyn.