The Self-Portrait Jorge Luis Borges Drew After Going Blind

For One Thing, You've Probably Been Looking at it Upside Down

Jorge Luis Borges always knew he was going to go blind. It was in his family: his father, his paternal grandmother, and his great-grandfather had gone blind before him and had died, he wrote in his 1977 lecture on the subject, “blind, laughing, and brave, as I also hope to die.” His case, he wrote, was not “especially dramatic.

What is dramatic are those who suddenly lose their sight. In my case, that slow nightfall, that slow loss of sight, began when I began to see. It has continued since 1899 [the year of his birth] without dramatic moments, a slow nightfall that has lasted more than three quarters of a century. In 1955, the pathetic moment came when I knew I had lost my sight, my reader’s and writer’s sight.

Borges called his own blindness “modest, because it is total blindness in one eye, but only partial in the other.” He could still see blue, green, and yellow, but not red or black. Yes, black. Shakespeare was wrong, Borges explained, when he wrote “Looking on darkness which the blind do see.”

One of the colors that the blind—or at least this blind man—do not see is black; another is red. Le rouge et le noir are the colors denied us. I, who was accustomed to sleeping in total darkness, was bothered for a long time at having to sleep in this world of mist, in the greenish or bluish mist, vaguely luminous, which is the world of the blind. I wanted to lie down in darkness. The world of the blind is not the night that people imagine.

This lecture on blindness also includes one of Borges’s most oft-quoted quips: “I had always imagined Paradise as a kind of library.” Usually, this is quoted without surrounding context: he is writing about the irony of being appointed director of the National Library of Argentina, in 1955, at the very end of his eyesight, and therefore basically unable to read, though he was still writing. “There I was,” he writes, “the center, in a way, of nine hundred thousand books in various languages, but I found I could barely make out the title pages and the spines.”

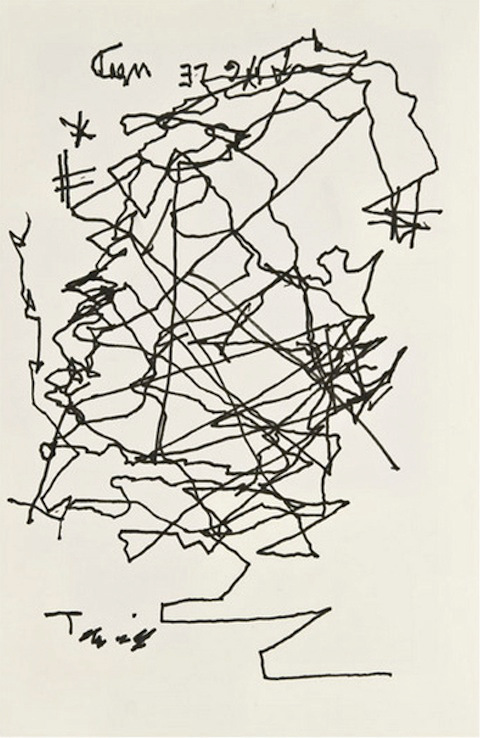

It was 20 years after this appointment, and after his final descent into near-blindness, that Borges drew this self-portrait for Burt Britton in the basement of the Strand in New York City. In the 1970s, Britton collected over 500 self-portraits of literary luminaries, first insisting they were only for his “private mania,” but later collecting them into a book, Self-Portrait: Book People Picture Themselves. According to Britton, Borges drew this self-portrait “using one finger to guide the pen he was holding with his other hand.”

“His translator brought him in,” Britton told The New York Times. “The portrait is perfect, but what I most remember was escorting him upstairs to the main floor, where it became clear he was listening to the room, the stacks, the books, and him telling me, ‘You have as many books as we have in our national library.'”

You usually see Borges’s self-portrait this way:

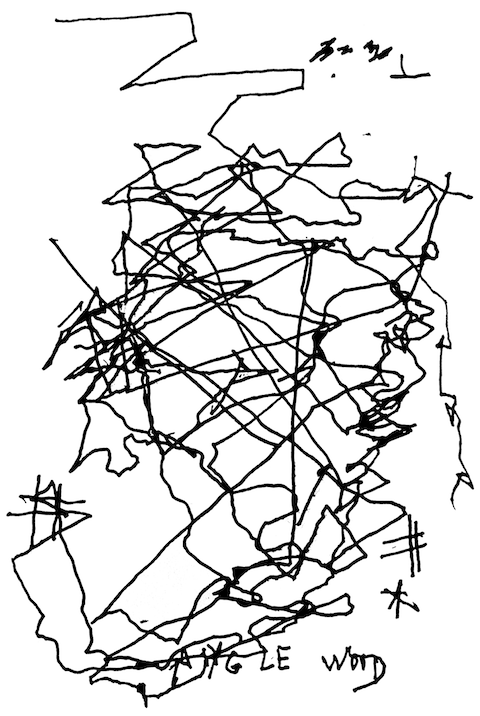

But in 1976, it was published in The Paris Review as part of an excerpt of Britton’s book, and presented like this:

I’d put my money on this one, considering the source. Though I have to say that it looks like he turned the sheet at least once while drawing, so both might be equally correct. But what has he written there at the bottom? It looks like TANGLE WOOD but I see that it is not. (Any other guesses out there?)

Borges, it should be said, was not exactly sorry to be blind. “A writer, or any man, must believe that whatever happens to him is an instrument, everything has been given for an end,” he wrote.

This is even stronger in the case of the artist. Everything that happens, including humiliations, embarrassments, misfortunes, all has been given like clay, like material for one’s art. One must accept it. . . If a blind man thinks this way, he is saved. Blindness is a gift. I have exhausted you with the gifts it has given me. It gave me Anglo-Saxon, it gave me some Scandinavian, it gave me a knowledge of a medieval literature I didn’t know, it gave me the writing of various books, good or bad, but which justified the moment in which they were written. Moreover, blindness has made me feel surrounded by the kindness of others. People always feel good will toward the blind.

I’ll leave you with one final thing, a poem Borges wrote about his own blindness, titled (I imagine) after Milton’s sonnet on the same subject:

On His Blindness

In the fullness of the years, like it or not,

a luminous mist surrounds me, unvarying,

that breaks things down into a single thing,

colorless, formless. Almost into a thought.

The elemental, vast night and the day

teeming with people have become that fog

of constant, tentative light that does not flag,

and lies in wait at dawn. I longed to see

just once a human face. Unknown to me

the closed encyclopedia, the sweet play

in volumes I can do no more than hold,

the tiny soaring birds, the moons of gold.

Others have the world, for better or worse;

I have this half-dark, and the toil of verse.

Emily Temple

Emily Temple is the managing editor at Lit Hub. Her first novel, The Lightness, was published by William Morrow/HarperCollins in June 2020. You can buy it here.