The Seductive Allure of the Real: Remembering the Humble Origins of Saveur

Dorothy Kalins on Perfecting Food Photography—and Rejecting Overblown Editorial Productions

Food photography, when I was a young editor, was a full-scale Hollywood production. Photographers used an eight-by-ten-inch beast called a view camera. This hulk, this Terminator—and determinator—of a camera was fixed on heavy wooden legs, and in order to even see the image on the camera’s ground glass, you had to duck under a voluminous black cloth. And unlike with a single-lens reflex camera, that image was upside down! So, say you were shooting a Thanksgiving turkey (which all home magazines were condemned to do). The setups were so cumbersome that the turkey had to be almost nailed to a table. You could move props around it, but once you decided on the shot and the super-hot lights were fixed on their metal stands, the camera itself did not move.

With a fixed camera, you had to figure out where the watercress should go and put it in the shot and then scurry back under the black cloth and turn your head upside down to see if you’d got it in the right place. Try making an enticing photograph under those circumstances. (Eventually, a Polaroid film holder was developed that could be attached to the 8×10’s ground glass so we could take test pictures and see the image the right way.) I learned from Carol Helms, design editor of Met Home, how to navigate such a photo shoot. It was miraculous to watch her get the watercress right, every time. (Well, give her any five unrelated objects and she’d work her magic and make them look as if they were born that way.)

Those old photo setups required a blinding blast of light on the set that further distanced the image from the real thing. None of this fit our editorial vision of making our pages look cookable. It took many unnecessary years for separators to accept film from smaller format cameras. (Believe me, I know how nutty this sounds today, when we’re used to holding up a small rectangle to our eye and digitally recording our every bite.) You’d leave a photo shoot with frustration; when you eventually saw the printed page, the last emotion you’d feel was the burning desire to cook the food.

Met Home was owned by the big Midwestern publisher Meredith. Before the success of our magazine earned its move to New York, we had to produce photo shoots in the basement of the corporate headquarters in Des Moines, Iowa, rummaging among the blue-flowered CorningWare and piles of polyester napkins in the vast prop rooms of Better Homes & Gardens, testing our recipes with olive oil I’d have to carry from New York (small wonder they called Iowa then the “land of two Velveetas”—with pimentos and without), borrowing our bowls and plates and platters from antiques shops in West Des Moines, relying on the goodwill and unfailing eye of Jim Hirsheimer, editor and antiques dealer (and eventual husband of you-know-who).

The food we showed on our pages would come a whole lot closer to the food readers could cook in their own kitchens.

By the time we launched Saveur, we would not even think about photographing our food in a studio. We moved into a sunny loft in SoHo with great old factory windows and abundant available light. (Light so awesome that if we were lucky, we’d look up and see the sunset caught in Rachel Whiteread’s glass water tower on a rooftop a few blocks away.) We would cook in our newly installed IKEA kitchen and carry the dish to a big worktable in our common space to shoot it. No fake barn-board backgrounds, no fantasy sets, no extraneous props. No watercress. No food stylists! Or prop stylists! Our food would look the way we editors wanted it to look. Just-cooked. Doable. Authentic. Delicious.

All of this played directly into the way Christopher wanted to shoot food. She was the right girl in the right place. She learned photography the way she learned cooking, by looking and doing, perfecting her skills (“Keep pushing the buttons!”), and trusting her artist’s instinct for what was right. It was the value of visual storytelling—truth-telling. The food we showed on our pages would come a whole lot closer to the food readers could cook in their own kitchens; it had the advantage of being real. Christopher’s photographs—bathed in natural light, emotionally immediate, beautifully composed—moved readers; she helped to reduce the frustration and fear of failure inherent in all kitchen endeavors and established a style that continues to be seductive to this day.

I have a memory of Christopher sitting on the floor in some hotel room somewhere in the world, surrounded, like the statue in the center of a fountain, by a daunting array of equipment: cameras and backs of cameras and pieces of cameras and all manner of lenses and filters and techy matte-black tripods and piles of film rolls (yes, there was film!) and cans of shot film. And she was just chatting away as she calmly organized those disparate parts, serenely making sense of it all. How remarkable, I thought. She has taught herself to know exactly what to do with every one of those little black pieces. (“Like with like,” I can still hear her singing in the process of organizing whatever chaos she confronted.)

With Christopher shooting many of our stories and Colman writing them, instead of working as editors with a photographer to produce the pieces and a writer to report them, we increased our editorial fleetness. Unlike the magazines we competed with—with their enormous prop and travel budgets and a cast of dozens—we had neither the money nor the inclination for such overblown productions. We could travel lighter, argue more, discover the real story as we went along.

Undaunted and unflappable, Christopher rode on the back of a scooter in Hanoi to photograph the celebration of Tet. She made a couple of sentimental journeys to Australia, once with Colman, which involved covering so many wineries I feared they’d never return. And one night, she called me from Valencia to report that all the snails they’d bought for the paella shoot had escaped from their baskets and were crawling up the walls of her hotel room.

__________________________________

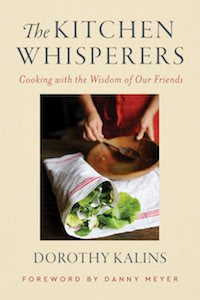

Excerpted from the book THE KITCHEN WHISPERERS: Cooking with the Wisdom of Our Friends by Dorothy Kalins. Copyright © 2021 by Dorothy Kalins Ink, LLC. From William Morrow, an imprint of HarperCollins Publishers. Reprinted by permission.

Dorothy Kalins

Dorothy Kalins is an award-winning magazine editor, the founding editor-in-chief of Metropolitan Home and of Saveur magazine, and the former executive editor of Newsweek. She has collaborated on the production of many award-winning cookbooks, including David Tanis’s A Platter of Figs, Michael Anthony’s The Gramercy Tavern Cookbook and V is for Vegetables, and Michael Solomonov and Steven Cook’s bestselling Zahav and Israeli Soul.