My mother is standing on the porch in the Adirondacks, her back to the lake.

The family place here is an old-fashioned camp, which my father’s father and a group of his friends purchased for hunting and fishing in 1923. There are several cabins, a big kitchen building, and a living-room building with this porch outside it. Below that are a boathouse and docks that give onto a lake encircled by small mountains named for minerals—Copper, Silver, Iron. The other families are long gone now; for us it’s a summer vacation place where we share and divide the time with cousins.

My father came here every summer of his life, and my mother, every summer of their marriage. It was the place where we marked the progress of our childhoods—where we swam and rowed, learned Liar’s Dice and Scrabble, climbed mountains and played prisoner’s base. Other than playing tennis on the dilapidated court, my mother didn’t like being there much—too isolated; she looked awkward on hikes, but right at home lying on this porch reading. Once in a while though, she’d initiate “a new phase”—as when she conspired with my most mechanically minded cousin to purchase a motor boat (long forbidden by Gramps, now dead). The purpose was not to replace the old guide boats and canoes, but to institute water-skiing: Really, what’s the point of the lake? She took up waterskiing with a competitor’s panache, skimming the sparkling surface, one of my brothers steering the boat in fast, wide loops until she wiped out amid cheers to begin again.

Just now, with a friend, I’m setting up writing space in the dining room. We push the long table to make room, and as I turn, I feel my mother so powerfully I say, “My God, she’s actually here.” It’s the end of August 1969, and I am walking toward her, along the boardwalk. The day is cloudy and she’s wearing long pants and a crookedly buttoned cardigan. In my memory, what was meant to be a small goodbye before I left the camp became momentous; at the time, I was simply leaving in half an hour for my new life. I think we must have talked a bit before she said it.

“I’m having some problems with my marriage.”

I’m sure she thought she was confiding; I’m sure she needed to tell someone. I know now that for her to admit such a thing to anyone was brand new—part of what she was talking about when she told the oral historian she wanted to be more honest. But as with many revolutionary acts, there were unforeseen consequences.

I am having some problems with my marriage, said the mother. The daughter was so shocked she hardly understood what the mother was saying.

I don’t remember answering, but I do remember what I would have said if I’d had any idea what she was talking about. Didn’t she know that this marriage also belonged to my father and to me and to my eight brothers and sisters? She looked so helpless there in her strange sweater, the wrong button in the wrong hole.

I have the letter I wrote her two days later, and I remember writing it, sitting on a bed in Gordon and Masha’s apartment in Cambridge—they were the couple who had taken care of me after the abortion, and now they were taking care of me again. I liked the way they lived, eating vegetables and brown rice, an apartment with no doors between rooms, calm, quiet voices. “Why don’t you write your mother a letter?” Gordon may have said.

As I read it now, remembering myself at twenty-three, I think I must have wanted her, miraculously, to understand everything and make everything all right.I wrote in turquoise felt tip on onionskin paper. What I had to say roared out of me:

September 4, 1969

Dear Mommy,

I’m sorry I was rude on the phone this morning, but I can’t help the fact that my feelings about you are extremely ambivalent at the moment. I would have thought you might have gathered that my decision not to go to Chicago to live with Arnold was not entirely a happy one—

As I read it now, remembering myself at 23, I think I must have wanted her, miraculously, to understand everything and make everything all right. What I said was that there was a lot she didn’t know about me: “I want to know you as a person,” I wrote, “but the mother-daughter thing confuses it a lot.”

The anger that you have gotten & are beginning to get again now has to do with my not having felt known & taken care of as your daughter, as a child & adolescent. I did try and make my terror of my plans clear & my general unsteadiness must have been obvious—so then you say (just a half hour before I leave), “I am having some problems with my marriage.” Now, are you being a mother or a friend? And if you are being the latter, do you have the right to be, to your daughter, about the marriage that produced her? And as the mother, wouldn’t you have been more sensitive to her state of mind or something? (It would have been different if you had said “Poppy & I are having a few problems with our marriage” for instance).

After I left her, I went straight to the Berkshires to pack up after the summer and managed to see a psychiatrist. I wanted her to imagine the worst, that I was turning into her manic-depressive, distressed mother and it was all her fault. How could she not know that everything in my life was falling apart: “Arnold, you, the end of school, the terror of beginning a new life.”

At the end of the letter, I was merciful and proud: she should know that “I am very excited, happy & on the upswing” (the phrase she often used to describe the better phases of Margarett’s psychological condition).

A week later, I got a letter from my father: “Sorry you have had such a rough time Chicago-wise etc. Things are a little bumpy here as I guess Mom indicated.” Neither revealed any details: that she actually wanted to leave the marriage, that he was—“Very angry. Hurt . . . sometimes inside my spirit & sort of in my mind, and sometimes in my chest, hurting hurting hurting.” The likelihood that he would be elected bishop of New York had precipitated a crisis. Turn down the job, he reported my mother saying, “knowing I couldn’t accept the suggestion.” Or she could stay in Washington? Nothing formal, rather living separate lives “sort of indefinitely until one of us wants to get married.” At the time, canon law of the Episcopal church forbade divorce even among laypeople and priests, except with special permission—in practice, a divorced man could not be bishop. “I think I will put it to her,” my father mused in a notebook, “would you want to leave the house if it meant leaving the children?” Of course there was always the chance he would not be elected.

Years later, I asked my sister Rosemary about that summer, and she reminded me it was the summer she and George went to Europe with my parents, as Paul and Adelia and I had in 1960. They visited a friend on the Greek island of Hydra and then went on to Athens. My mother had an almost disabling toothache, Rosie remembered. Talking once about those years, my aunt Margie remembered the toothache, and another story Jenny told her about that trip: that they were joined one night at a restaurant by a younger Episcopal priest “and some other people.” Such a coincidence that they were all in Athens at the same time! My mother did not believe it had been a coincidence, she told Margie. She felt, she said, “a frisson” between my father and the priest. Margie did not remember this detail until decades after my mother died: “I blocked it,” she said.

Writing history requires putting one thing next to another thing. When my mother told me that morning in the Adirondacks that she was having some problems with her marriage, I could not imagine what was wrong because I had no other thing to put next to what she said. At the time, what my mother felt—a sexual charge between her husband and another man—had the disorienting power of an unexpected assault. How could she not have known this? And she always believed their sexual problems had been hers! “She told me she thought he was the unhappiest man she’d ever known and that he was homosexual,” said one of the three women with whom I talked about my father’s secret.

“And so it was true,” said Margie, “and I never believed her.”

“Please go carefully if you write about it,” said the third friend. “She did love him, and you owe it to your father.” When I learned about his hidden life twenty years later, I had no judgment of my father—rather, a complicated blend of shock, sadness, and betrayal. Toward my mother, by then long dead, I felt a new mother-bear protectiveness.

My mother and I begin to stumble toward new terms of engagement—as free women.In light of the incident at the café in Athens, what my mother said to me that morning on the porch was a drastic understatement: I am having some problems with my marriage. Even though a sequence of moments had built to her conclusion, the actual realization must have seemed to come out of the blue, as if a cataclysmic storm could descend when the sky was clear and the sun was out. That she did not ever confront my father or reveal to any of her children her suspicions was certainly self-protective, but it was also an act of extraordinary generosity. My father was at the height of his heroism, about to enter the triumphant chapter of his life. I thought I had to be ambitious for him, & I was is her surviving statement on the matter. Her continuing silence was a choice—I found no mention of my father’s sexual conflicts in any of her papers. If she ever wrote about it, she must have destroyed those pages before her death. I wonder when or if we would ever have talked about it.

Eighteen months after our moment on the porch, my mother will write me about the play that is in my head “Women, Mothers and Daughters”—I want to deal with who has a right to “hurt” whom? Can daughters “hurt” mothers or is that something else, like “acting out”? My thought of yesterday: set will be a lot of mirrors (among other things) some mirrors may get broken, etc. etc. At my suggestion, she was reading The Golden Notebook by Doris Lessing, in 1970 the only novel around about contemporary women trying to hack out independent lives. Lessing used the phrase, “Free Women.” And so, my mother and I begin to stumble toward new terms of engagement—as free women.

*

As I stand at the entrance of the Chelsea Hotel with my suitcases, I can’t help noticing that all the writers commemorated there by bronze plaques are men and now dead—often of suicide—and that, like those men, I’d come here to write. In the lobby hung paintings by Arnold’s best friend Larry Rivers, and in the elevator women my age with sunken eyes and dull blond hair looked up at the ceiling and scratched their forearms. That final spring at Yale, I’d fallen in with a group of people who wanted to be “brilliant writers,” who were in graduate school solely to avoid the draft. One friend had quit the school anyway, beginning years of changing his address—“I’d move before I got any mail from the draft board and send them a change of address form; eventually they gave up on me.”

Now he was in Massachusetts writing a novel, and he thought I should write one too, so I set myself up, turning my desk to face a pair of French windows that looked out on 23d Street. A few days a week, I went uptown to an office where I was raising money for the play I was coproducing with my friend Ann—we had hired a director and were looking for a theater.

What do I remember from that fall? For the first time, I ate Häagen-Dazs ice cream, which then had only three flavors: vanilla, chocolate, and boysenberry sherbet (sorbet but not yet called that). My first night in town, Ann and I had supper at a Japanese restaurant on Eighth Street, and an actor who had made his name off-Broadway sat down with us. He had just turned down a part in a film, he was proud to tell us. Later he would become a movie star named Al Pacino. That summer, in the Berkshires, I’d met a writer named Venable, a playwright and screenwriter who had written a movie called Alice’s Restaurant, about the draft and people I sort of knew in Stockbridge. I had a crush on him, so I invited him to a party at my Berkshire rental; late in the evening, I asked to kiss him. He said no, he was living with someone. Couldn’t we just have lunch? No. I talked to Ann about him all the time, shocked at the plots she devised to help me steal him from the girlfriend he was living with in Los Angeles. Once a week I went uptown to see my new psychiatrist.

And then one night, Arnold called from Chicago. He was coming into the city, did I want to have a drink? I hesitated, but within seconds acquiesced. We had dinner, and afterward, he came back to the Chelsea with me and we took the elevator to my room—lovers again, it seemed. He would be in town for several weeks, he said. He was translating the Bertolt Brecht–Kurt Weill opera Mahagonny for the man who had produced their legendary Threepenny Opera, which had run forever off-Broadway. Having Arnold in my bed put an end to my novel; again he ranted and raved about the irrelevance of anything I might write. I didn’t have the strength to tell him I didn’t want him to move in; and anyway, maybe if we were together again, that awful brokenness I was still feeling might dissolve.

Soon all my hours were for him, listening to him on the phone with Larry Rivers or the director called Carmen—an odd name for a man, I thought—or a poet named Kenneth (Koch, I learned when we had dinner with him). I took a break from coproducing the play, which was, I wrote my mother, “very funny, a panic” by a woman just five years older than me, a comedy about three women roommates in New York. I told my psychiatrist I couldn’t be sure Arnold and I wouldn’t get married. I don’t remember if I typed up his translations of Kurt Weill’s lyrics, but I might have. I would go with him to the producer’s high-ceilinged apartment on West 10th Street, sit and wait for hours while they worked out the translation of another song (the director played the piano). Then Arnold and I would have late supper at a place called Casey’s—Casey was Japanese, and the restaurant was French and delicious; an expensive meal was $10.

Afterward maybe we would go to Bradley’s, the jazz bar a friend of Arnold’s had opened on University Place. Though I considered myself barely corporeal as I sat through those smoky evenings, most of the people I met in those days remembered me when I met them a life later in New York. Others I read about in the New York Times decades later when they died: Paul Desmond, Elvin Jones, Iris Owens, Bradley Cunningham. Some of the poets I met then or I would come to know: John Ashbery, Anne Waldman, Bill Berkson, Harry Mathews. All of them were still talking about someone named Frank—a poet named Frank O’Hara who had died in 1966.

It took only days for the romantic idyll to end, and a week for the sex to wind down, but Arnold stayed on. “I’m at the Chelsea,” I’d hear him say on the phone, at night find myself in bed alone after midnight waiting for the sound of his key in the lock. “I’ve got to work late on a song,” he’d say, calling at 2 a.m. “I’ll be home in no time, Pussy.” (He knew I hated to be called that.) My psychiatrist declared Arnold “exploitative” and advised that I ask him to move out.

I didn’t need to; he soon left abruptly for Chicago, and in November I visited him for a long weekend. Pam and Jim Morton lived there now, and I had tea with Pam while Arnold was teaching a class. It felt comforting to talk to someone I had always known, since Arnold was, as usual, barely present. The only letter I have from Pam to my mother is about that visit: “He sounds brilliant, but I can certainly get the picture of how complicated it all is, as Honor herself was the first to say. I think that the visit was really hard for her—not entirely sure why, but his preoccupation with the job + her having to pitch in + be supportive when she felt like being supported (how’s that for a marriage in-spite-of-itself situation) had something to do with it, I gather.”

Pam’s take on the situation was pitch perfect. I was using every bit of my imagination to act as if I was not unhappy. Arnold was not affectionate, he did not take me to rehearsals, and he kept saying that I didn’t “help” enough. I didn’t know quite what he meant since I had unpacked all the books and records, including my full set of the Beatles, bought bookshelves, put all the books away, and scoured the kitchen, scrubbing and arranging, while he went off to teach, only to return hours late and fall immediately asleep. Soon I was back in New York, having agreed to sublet his apartment on 13th Street. Actually, I wanted to stay at the Chelsea, but I couldn’t bear the thought of separating from Arnold so I rented his “great place” for $150 a month.

It was a bit ratty—uncomfortable battered furniture, his books, tired dishtowels, paintings: a small Jane Freilicher landscape, an Andy Warhol silk screen of the exploding atom bomb—black on brown paper—that I rolled up and stowed beneath the desk. The apartment was a floor-through. In the room you entered, there was a round table—“Moroccan,” Arnold said—and a small kitchenette off to one side. “Isn’t the terrace great!” he exclaimed the first time he called. I never used the terrace, which was the tarred roof of the Italian restaurant beneath—it got sticky when it was hot outside. I was used to terraces of flagstone shaded by espaliered apple trees, like the one at Hollow Hill.

Once I was finished crying, I began to write enraged fragments that wished to be poems and piled them on the Moroccan table.Soon, Arnold promised, he’d be back for rehearsals of Mahagonny and my certain reign at his side, girlfriend to genius. One day late that fall, I was visiting friends on the Upper West Side when another friend turned up from Chicago with the news that Arnold had married a woman named Suzanne. Could this be true? Yes. Wasn’t I living in his apartment, waiting for his return? Hadn’t he called me just last week, the same sexy endearments? It was all I could do to keep myself from weeping in front of my former teacher, his lover, and the classmate who had delivered the news. How could I have been so stupid? Those long nights “teaching,” he’d been with Suzanne!

“Do you have fantasies,” my psychiatrist asked? I said I could see myself with a gun, pointing it at Arnold from a vantage point on my bed. Is that a fantasy? The psychiatrist smiled and nodded. I also had fantasies about Arnold and his new wife, which I tried to banish. Once I was finished crying, I began to write enraged fragments that wished to be poems and piled them on the Moroccan table. Some days that fall I’d go downtown to Wooster Street and sit in on rehearsals of a dramatization of Naked Lunch that fellow drama school dropouts were putting on. It was one day that fall that I drove a bunch of us up to Vassar to see the Open Theater and heard of a movement called women’s liberation—it turned up soon after in the Village Voice—a long article about something called an abortion speakout.

My own abortion had been safe, and I hadn’t died; I couldn’t possibly belong at such an event. I was too embarrassed by my clearly retro connection to Arnold to seek out the feminists, but I did once meet a lawyer named Flo Kennedy—later she said that because I’d asked her where to find the Black Panthers, she thought I was an informer. I tried to put my heartbreak behind me as I worked on the play. My mother had sent in a $750 investment toward the $4,000 I had to raise.

For comfort, I went to New Haven to visit my friend Lily, an African American woman whose Black Panther husband was in jail; I had helped her financially after their son was born. I showed her my poems and she took me to a poetry reading at a bar where there was an open mic—there I stood and read my own poems for the first time, brittle and furious. When I finished, Lily clapped loudly and assured me that someday Arnold would regret losing me. Many years later she was proven correct; but at the time, I believed that I was a failure as a radical and a woman and that my writing was nothing Arnold would ever appreciate. “You’re not writing for him,” Lily would say. “You’re doing it for yourself.” A good idea, I thought; why couldn’t I feel it?

It took decades, but Arnold and I eventually became a version of friends, and he’d tell me repeatedly what a terrible mistake he’d made all those years ago. When his translation of Mahagonny was finally performed at the Metropolitan Opera sometime in the 1990s, I went to the opening, the old sorrow washed away when, weeping, he took a tuxedoed bow in the curtain call with the conductor. By then in his seventies, he could still make me laugh in that particular way. Months before he died, I ran into him on the street, and he insisted I sit down with him for a cup of coffee. I had only 15 minutes before an appointment, but I happened to have a galley proof of a new book of my poems, which I gave to him.

“I love you and I have always loved you,” he said, taking my hands. “I’m so sorry I hurt you so much, and I’m very happy you found your way to poetry.” It was the last time I saw him. How had this man, so old and tired, ever caused me such pain? In that moment, I felt much closer to how he had inspired my writing than to the great heartbreak that defined my first years in New York.

__________________________________

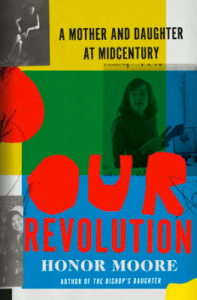

Excerpted from Our Revolution: A Mother and Daughter at Midcentury by Honor Moore. Copyright (c) 2020 by Honor Moore. Used with permission of the publisher, W. W. Norton & Company, Inc. All rights reserved.