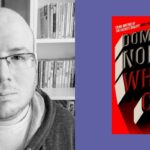

The Right Kind of Doll: Sarah Moss on the Prides and Pressures of Girlhood

“You knew... that taste was indistinguishable from morality and yours wasn’t good enough.”

Other people had Barbie and Sindy dolls. You couldn’t tell the difference, they were both blonde and blue-eyed and exquisitely thin, and they both came with beguiling wardrobes of sparkly sheer synthetic fabrics, ballgowns and evening dresses, tiny high-heeled shoes for their tiny high-heeled feet. They had hairbrushes, which had to be bigger than the shoes so you could brush their hair with your clumsy human fingers, and tiaras and sparkly hair-clips like ballet dancers. (You were sometimes taken to see the ballet, because it was art, especially with the orchestra playing nineteenth-century music, even though there were also pink silk shoes and sequined tutus and the dancers’ legs were bare right up to the top and they often wore strapless tops and danced en pointe, which ought to have been even worse than high heels if the objection was to women crippling themselves for beauty.)

You went to other people’s houses to play with their Barbies and Sindies and with their dressing-up boxes which included their mothers’ old handbags, patent leather and, let us hope, fake crocodile and snakeskin, with metal snaps you could twist and stiff silky linings that smelt of perfume and powder. You used to try on their mothers’ old high-heeled shoes, a net curtain on your head being a veil though not usually bridal, just feminine, just pale and sheer and lacy, and old party dresses from dancing days.

The Jumbly Girl preferred backpacks, hands free for the pram or the shopping, never touched make-up, wouldn’t have been seen dead behind a lace curtain and the thing is you’re the same now, aren’t you, you travel the world, show up at posh literary festivals, with a tatty hand-luggage-only backpack, won’t use a wheelie suitcase because it slows you down, because how’s that supposed to work when you need to sprint to make a tight connection at an airport or a station, or when you decide to spend a day hiking between hotels? You sometimes buy high heels but you never wear them, because who wants to be caught by shoes in which she can’t run away, and you sometimes buy makeup but you don’t wear it, not even on stage or for photos, and as for the lace curtains—so you can’t say she was wrong, not unless you’re wrong too.

You had a party for your sixth birthday.

Right, so don’t try any more sob stories, if this is meant to be some kind of misery memoir it’s not going well.

Before you started school, not long after the Angel Boy was born, you had moved down from Scotland to a large Victorian house in Manchester, the sort of house casually acquired by the Owl and the Jumbly Girl’s generation that would be far beyond the dreams of their children and urgently resented by their grandchildren. They’d been characteristically ambitious, bought a doer-upper with the idea of doing it themselves, so for years the house remained unfinished, missing floorboards, offering exciting access to the subfloor where there were wires and pipes you weren’t supposed to touch but who could help just brushing as you crawled past?

You sometimes buy high heels but you never wear them, because who wants to be caught by shoes in which she can’t run away.The little girls who came to your party hadn’t seen a subfloor, didn’t know their houses’ bones and veins, though you all lived and went to school and the library and the shops in Victorian buildings; in some ways growing up in Manchester was growing up in the nineteenth century, amid the Thatcher-ruins of empire. The Jumbly Girl made healthy versions of party food—not that you wouldn’t do the same, thirty years later, not that you wouldn’t want to slap other people’s children who picked apart your home-made low-sugar wholemeal apple muffins—but you hardly noticed because of the presents, because every little girl had brought you a gift wrapped in brand-new shiny paper.

And their mothers didn’t understand that most dolls were nasty plastic tools of oppression bought by daft tarts who didn’t know any better, didn’t bother to seek out the dark-haired dolls with soft childish bodies, much less the brown dolls who still came with shiny straight nylon hair, which meant that this year you unwrapped a thing you’d coveted and never thought to own: a pale-pink head and shoulders, cut off above the boobs like a marble bust, with long blonde hair and a dial between the shoulders that you could twist to make the hair longer or shorter, and she came, this decapitation, with a set of hairbrushes and clips and ties and also a set of make-up, blue and green eyeshadow, a whole palette of lipsticks and blushers, brushes smaller than those in your watercolor set.

You’d never even have bothered wanting such a thing, it would have been like wanting a swimming pool or an ice rink, a pointless thought, but here it was, yours to groom and play with. Only in the morning it was gone, and when you asked she said, yes, we took it away, it was stupid, it was plastic and ugly and we won’t have such a thing in the house.

The house, as it was finished, was painted in dull shades of brown and green. There was old furniture, fragile, not to be jumped on, some of it carved with what appeared to you to be grinning skulls. There were floor-length curtains at the original leaky sash windows, also in strong dull colors, patterns you would later recognize as William Morris, patterns you would later covet in brighter colors for your own smaller cold Victorian houses. There were hand-thrown mugs and bowls thickly glazed in shades of oatmeal, beige, sage. You thought it needed more pinkness and sheen, more lush nylon carpet like in other people’s houses, maybe some china kittens and fairy pictures instead of the paintings of severe landscapes in severe weather.

You could see that your present didn’t fit and you still wanted it back, in the bedroom the Owl had papered with the pink butterfly pattern you’d chosen, under the ceiling he’d painted pink for you, because it’s true that he did, always, understand the need for a room of one’s own, always understood that a person might feel safest alone, behind a door that closed with a slippery handle, in a cloud of smoke above a flight of creaky stairs. You wanted to paint the plastic face and arrange and rearrange the golden hair, and you knew it was you, really, who was stupid and ugly, you knew that wanting stupid and ugly things was the outward sign of your stupidity and ugliness, that taste was indistinguishable from morality and yours wasn’t good enough.

Lulu’s family did not have taste.

They’re nice enough people but when you’re older you’ll understand.

Lulu did tap-dancing, not ballet. Her mum was a nurse and her dad worked in a biscuit factory and brought home an astonishing cornucopia of misshapen pink wafers and chocolate fingers and custard creams, refined flour and sugar and vegetable fat and artificial colors and preservatives casually supplied as if they wouldn’t make you fat and rot your teeth and corrupt your soul, not that souls were really a thing there and then, not that anyone spoke of morals because all that had been displaced. It was fat that was bad, physical weakness was moral weakness, ill-health was either malingering or neurosis, goodness subsumed into correct taste and the control of the body.

Strange, you think now, for feminism and anti-racism to coexist with essentially fascist thinking about the body, especially as the Jumbly Girl began to work in disability rights. (Was it part of her rebellion, this tacit defense of the deviant body?) You understood that Lulu’s family weren’t as good as your family because they kept their small house so warm you didn’t need a jumper, called their dinner “tea” and ate it—processed muck from a box—on their laps in front of the gas fire and the television, another box producing processed muck.

__________________________________

From My Good Bright Wolf: A Memoir by Sarah Moss. Copyright © 2024. Available from Farrar, Straus and Giroux, an division of Macmillan, Inc.