The Rest is History: Andrew Ridker on Writing About the Recent Past

“In a world that changes as rapidly as ours, all fiction is historical fiction.”

For years I refused to read historical fiction. It seemed to me that there was something artificial—dishonest, even—in summoning a time and place that hadn’t been experienced firsthand. I couldn’t see past the affected dialogue, the funny hats, and my suspicion that the author was making it all up, like science fiction in reverse. To me, the purpose of literature, if in fact it had a purpose, involved making sense of the world as it is—not as it was.

If I wanted to read about Russia in the nineteenth century, I could pick up Anna Karenina. Surely Chaucer could tell me more about the Middle Ages than an MFA. Consequently, when it came to contemporary fiction, I gravitated toward books that engaged in some way with the zeitgeist, broadly defined—stories that could tell me something about The Way We Live Now.

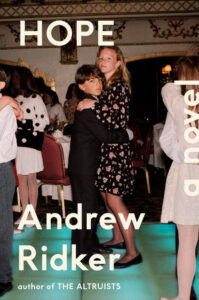

My first novel, The Altruists, was one such book. Written during and largely set in the Obama era, it was dense with up-to-the-minute details and tackled what I felt to be contemporary concerns. But as I started work on what would become my second novel, Hope, I realized I wasn’t done with that period of time, or rather that it wasn’t done with me. I was still writing about the 2010s, only now I was doing so from the 2020s.

This was more difficult than I’d imagined. There had been so many crises and upheavals since Obama—Trump, #MeToo, Parkland, Comey, Kavanagh, and COVID, to name a few—that his presidency, however recent, seemed inaccessibly remote. It wasn’t that I’d blanked out the Obama era; I was in high school when he was elected, and graduated college toward the end of his tenure. In other words, those were some of my formative years.

But in the summer of 2020, isolating in my childhood home while my phone shook with apocalyptic push notifications, I had a hard time remembering how those years felt. The optimism I associated with Obama’s early years was in short supply as COVID tore through hospitals and protestors took to the streets demanding racial justice. Sitting at the desk where I’d once done my homework, the surface scratched by a long-since-deceased family dog, I realized that if I was going to access the Obama era, I would have to treat it for what it was: history.

I read books about his presidency: The Bridge by David Remnick, We Were Eight Years in Power by Ta-Nehisi Coates, A Promised Land by the former president himself—and pored over news articles from the Times archives. It helped to remember, for example, that the city of Detroit filed for bankruptcy in 2013, or that Obergefell v. Hodges legalized same-sex marriage at the federal level less than two years after that.

But data points like these could only take me so far. Making playlists of the chart-topping music of the time—upbeat party anthems by the likes of Bruno Mars and Katy Perry—turned out to be a more effective means of conjuring the feeling, if not the substance, of the era. Art and entertainment have a way of doing that, and perhaps especially in this case; Obama was the quintessential pop culture president. Before I knew it, I found myself compiling what trend forecasters call a “cultural matrix”—a vibes-based reference guide to the 2010s.

At one end of my matrix was Parks and Recreation, the political mockumentary series that first aired four months into Obama’s presidency. Parks and Rec presented an idealized look at local government, in which liberal Democrats and Libertarians do not butt heads so much as exchange playful shoves. As Alan Sepinwall wrote in Rolling Stone, “Few series in recent memory have been as clearly tied to a moment—and, specifically, a presidential administration—as Parks and Rec. The show’s belief in the power of government to make people’s lives better…made it the standard-bearer for the hopefulness of the Obama era.” The show’s tone was in tune with its ideology: chipper, warm, and utterly uncynical. Politics, in the world of Parks and Rec, was less a power struggle than a pizza party.

At the other end was Lin-Manuel Miranda’s Hamilton, which opened on Broadway in August 2015, six years after Miranda performed an early version of the show’s opening number at Obama’s White House. (Ron Chernow, whose biography of Hamilton served as the primary source material for the musical, told the Times that the show has “‘Obama’s America’ written all over it.”) A hip-hop musical in which the Founding Fathers are played people of color, the play won a Pulitzer, earned Miranda a MacArthur “Genius” Grant, and grossed hundreds of millions of dollars.

But a backlash has been gaining steam in recent years. Miranda has been accused of glorifying slave owners and deploying color-conscious casting to tell an all-too-familiar story about American exceptionalism. As historian Lyra D. Monteiro wrote in The Public Historian, the play “can be seen as insidiously invested in trumpeting the deeds of wealthy white men, at the expense of everyone else.” Put another way, while Hamilton sounds like hip-hop, the song remains the same.

Taken together, these cultural artifacts and others on my matrix—Upworthy, Macklemore, Lean In—paint a picture of an optimistic if self-satisfied country; a country that sees itself as capable of making steady, incremental progress without dismantling, or even reforming, its institutions. In other words, a liberal country—and a complacent one. Any time I lost sight of that while writing Hope—a not infrequent phenomenon during Trump’s illiberal term—I consulted my cultural matrix and refamiliarized myself with the recent past.

Does that make Hope historical fiction? Not according to Sarah Johnson of the Historical Novel Society, whose definition requires that a novel be set more than fifty years in the past to qualify. But fifty is an arbitrary number, as Johnson readily acknowledges. “Whose past are we talking about,” she asks, “the reader’s past or the author’s past?”

Johnson’s other condition is that a work of historical fiction must be “one in which the author is writing from research rather than personal experience.” Setting aside the slippery notion of personal experience—the imagination plays a central role in the writing of even the most autobiographical fiction—I would have struggled to write Hope without the aid of research. Books, news articles, the cultural matrix: all of these were indispensable as I dreamed my way out of quarantine.

A novel succeeds not because it summons the past but because it speaks to us in the present, whenever that happens to be.But if a work of historical fiction is merely one that “has as its setting a period of history” and “attempts to convey the spirit, manners, and social conditions of a past age,” as the Encyclopedia Britannica would have it, I think there’s a case to be made that Hope qualifies. While the social conditions of the Obama era largely resemble those we know today, especially when compared with those of, say, the Industrial Age, I’d argue that the spirit of the times—the zeitgeist—was markedly different a decade ago. This is a fairly new phenomenon. Thanks to the internet, nostalgia loops are speeding up. The fashions of five years ago are already ripe for rediscovery. In a world that changes as rapidly as ours, all fiction is historical fiction.

Approaching Hope from that perspective gave me a newfound appreciation for novels more in keeping with Johnson’s definition of the genre. It was during the pandemic that I finally read Hilary Mantel’s Wolf Hall, a book beloved by pretty much everyone I knew and one that I’d nonetheless resisted. Seven hundred pages about a sixteenth-century statesman? And that was only the first volume of a trilogy!

But Wolf Hall, as its many admirers know, is a masterpiece of psychological acuity. While the novel, strictly speaking, takes place in England between 1500 and 1535, it would be fair to say that the novel’s true setting, much of the time, is the mind of Thomas Cromwell, Mantel’s protagonist. The immediacy of her narration—close third person, present tense—obliterates the distance between character and reader.

The style is modern, even if the subject matter isn’t. Which is not to impugn the depth and quality of her research: as a reviewer in the Guardian noted, “Mantel works up a 16th-century world in which only a joker would call for cherries in April or lettuce in December, and where hearing an unlicensed preacher is an illicit thrill on a par with risking syphilis.” But what I loved most about Wolf Hall was not its historicity. On the contrary: it was the novel’s timelessness, the insights into human nature that were true of Cromwell’s time and remain true in ours.

Since finishing Hope, I’ve made room on my shelf for more works of historical fiction, from the fine-grained realism of Willa Cather’s Death Comes for the Archbishop to allegorical alternate histories like Colson Whitehead’s The Underground Railroad. But the experience changed me as a writer, too. For one thing, I discovered, or rather rediscovered, my love of research, the thrill of finding in some dusty book or roll of microfiche a detail that ties everything together. What’s more, it gave me license to explore times and places I would have previously considered off-limits. After all, if my own past could be conceived of as historical, why shouldn’t I find myself at home in history?

These revelations led me to my next book, a work of (you guessed it) historical fiction. As it turns out, writing about 1913 isn’t all that different from writing about 2013—or 2023, for that matter. Research is important, details are important, but ultimately, a novel succeeds not because it summons the past but because it speaks to us in the present, whenever that happens to be.

__________________________________

Hope by Andrew Ridker is available from Viking, an imprint of the Penguin Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House, LLC.