The reservoir is why Ridley took this apartment eleven years ago. A view of water—so hard to come by in New York City. Perched high over Central Park without having to suffer the river winds and public transportation inaccessibility of East End or West End, Ridley could gaze out his big living room window twenty floors above the asphalt at the rolling trees and the oval of water, and if he squinted, so Fifth Avenue opposite him got squeezed out of his visual frame, he could be hovering like a local god over a big pond somewhere in New England. He could be Thoreau or Emerson brooding on escape and self-reliance in his cabin in the sky. Living that peculiar American fantasy of forsaking the world while influencing it, like designing a house one had no intention of ever moving into.

Ridley loved the water view so much that he was curating a series of time-lapse photos on his phone called “Res: 365.” He was proud of the triple play on words of “Res”—Latin for “thing,” but also a passable abbreviation for reservoir and resolution. Because these photos were both a thing about the reservoir and a resolution of sorts. They were him reaching out to the world, trying to say something with his eyes. They could be his legacy.

He’d had a successful enough under-the-radar career on Wall Street, and when he gold-plated parachuted out in 2009, he was still very young for retirement. There had been blustering talk of partly blaming his firm, among others, and by extension possibly him, for the American greed and financial malfeasance that had brought the world crashing down. Accountability was all the rage for a couple years, but that fever, that witch hunt for the subprime illuminati cabal of bad guys, had passed with the amnesia a return to normalcy and a humming economy bestows upon a society—with just a wave of Adam Smith’s invisible hand, he thought. Besides, he wasn’t a big fish. Nor would he be a fall guy. Neither hero nor zero, he enjoyed the safety of the middle. He’d done well enough, but he’d never been all in with risk. He was content to stay in his low-mid-six-figures lane year after year; it added up, and he had raised a family comfortably on it. Twenty-five nine-to-five years of the subway to and from his lower Manhattan office and summers on Fire Island were nothing to be ashamed of, but he suspected a straight money job never quite fit his soul.

But now, when people would watch his time-lapse films, they would learn of his depth. He was something of an artist. They would get to share what he was looking at, his angle and his timing, what he deemed worth framing and saving. Like the way younger people do on Facebook, he imagined—thou shalt know me by my posts.

There was a little groove in his windowsill when it was open that you could slip an iPhone into horizontally, use as a makeshift stand. For every day of this past year, before he went to bed, without fail, Ridley would set up the phone facing the reservoir. In the morning, he would retrieve the device and watch in time-lapse wonder (one frame every thirty seconds) at the play of light and dark, the unchanging change, the blips of ambulance headlights like fireflies, and the puny fireworks of red/green streetlights, the silent stillness of the sped-up sleeping city (an entire night flashed by in a few minutes), and then the sunrise over the East Side.

The city was injured, on its knees. Because . . . pandemic, like he heard kids say. He really had to squint if he didn’t want to see the big tents go up over on the east side of the park to catch the contagion’s runoff from the hospitals—like those mobile hospitals during wartime. He’d heard a rumor that the ad hoc structures were morgues, tents refrigerating corpses till they could figure out where to put them for good. His mother used to say, “The morgue is filled with optimists.”

Like Matthew Brady, Ridley considered himself a war photographer.

He wasn’t essential, and he didn’t need to work. He could order in for an eternity before feeling a pinch, supporting the struggling local restaurants with outrageous tips like a secret benefactor. The virus was everywhere and nowhere. But it couldn’t float up to his window. The virus couldn’t fly that far on its own, yet. There were rumors of mutations, a smarter virus educated by its interactions with humans, even a weaponized strain, but Ridley didn’t believe in that Internets shit. He didn’t believe in conspiracies. He had seen firsthand in his job that, while human greed was an organizing and destructive principle, it was not a conspiracy.

He believed in nature and science and history. And though death was in the air, he would remain brave and calm. Mankind had seen this type of suffering before; it was a mere cycle. The virus was bad, sure, but not unprecedented or special, nor would we be, he pondered, putting it all in perspective, when we survived it. History was pockmarked with such so-called unprecedented precedents. Well-read for a Wall Street veteran and self-styled collector of urban arcana, he knew that Central Park itself, before it was a park and a soft-focus locus for numberless romantic movie scenes, was an unmarked graveyard for enslaved people and indigents, a kind of potter’s field dumping ground for the disenfranchised. There must be unsettled ghosts from that, he imagined, and energy you could capture with a phone. Restless spirits of Black men and women who had not been properly memorialized or compensated. Though he was a rational man, he half hoped his lens might catch that, like historically revisionist ectoplasm in the spooky mist of the reservoir.

Although ailing, the city was unified these days in a brotherhood of victimhood, like it hadn’t been since 9/11, galvanized against a common foe in ways that transcended distinctions and identities. He liked this downtrodden esprit de corps. He didn’t partake of it directly, didn’t go out much at all, though he did stand proudly at his window at seven p.m. every evening to clap and cheer and bang pans for those on the front lines. Some days, that spirit of communion would bring a small sob out of him, for it was so moving to be grateful and to be a part of something in these isolated times. An old man just across the street uptown would stand on his deck and blow a small horn or bugle. Though Ridley could produce a piercing taxi-whistle through two pinkies beneath his lower lip, he envied that cool bugle—a “slughorn” he wanted to call it for some reason. So the two men, in their aerie lairs, competed over who could make more noise for those on the streets, the essential workers, who could engage in a flashier show of gratitude.

He was over 250 days into this 365-day series of photos that he hoped to sell to a museum or gallery or just share with the world on a website or YouTube channel. He thought these pictures meant something. Like art means something. He wasn’t an artist, but did that mean he couldn’t make art? He wondered if he needed to know more about what he was doing—like did he need to know what he was saying or was it enough to know that he was saying something? Yeah, it was enough. The virus had made him want to say something; the virus was speaking through him like a ventriloquist.

If someone asked? It was about perseverance and reclamation, New York strength and universal brotherhood, and the ever-trending hope and resilience—big-ticket high-concept shit people loved to hear themselves bloviate about. It was about bearing simple witness. It was revelation through repetition and boredom, and recovering the vital truth of hoary clichés—chop wood, carry water / stop and smell the flowers / if you’ve seen one sunrise, you ain’t seen nothing yet. It was about looking at something for so long that you finally saw through it—like those trick holographic photos of Jesus the shepherd with eyes that followed you, the sheep, when you moved—only no trick and no Jesus. Aha, you thought you were the watcher, but all along you were the watched. It was about you. It transcended humbly. It was 10,000 hours manifest. It was zeitgeisty. Maybe he’d rename it something allusive, meaningless, and unassailable like “Temporal Pointillism,” or kicky, vaguely derivative, and just-pretentious-enough like “Seurat’s Pocket Watch.” But he’d keep most of that to himself, close to the vest—art was knowing when to clam up and what to leave out. He would drop some sphinxlike hints in dribs and drabs and let others fill in the blanks, and then he would take credit for their projections. They would bring their own meaning and value and blow him up like a big balloon. That’s the fun part of the art game.

He woke up this morning with a familiar thorn in his side, missing his daughter, Coral. He hadn’t seen her in person for ages. She was afraid of killing him. They were afraid of killing each other. He had been the first to say, months and months ago, that he didn’t want to see his grandkids while the virus was rampant, that they couldn’t be trusted to wash their hands consistently or not to absentmindedly pick their noses, etc. He said something like he didn’t want his fucking grandkids to kill him. Maybe he’d phrased it badly like that, or maybe, and this was more likely, the fact that he found his grandchildren somewhat exhausting and taxing and ultimately boring came through as subtext, and his daughter had parsed it, and she was mortally offended. It wasn’t just her kids; he’d wanted to say to her, it was all kids. He hadn’t been ready, might never be ready, to be one of those spectral, skinny-armed, gray New Balance–clad, grandpa Sisyphuses bent over pushing not a boulder, but a stroller, like a walker, through the park a second time around. He liked kids, he did, but he’d never been entirely comfortable with them, never knew how to talk to them, couldn’t participate in their tiny passions and jokes, and, of course, his daughter knew this best of all. He was better when they got to be about fifteen, that’s when the love he knew he had inside him started to flow more freely; he just needed some time to get used to them. Family wasn’t his thing, necessarily. His own brother had taught his numberless nieces and nephews to call him Uncle Awol. His brother was a funny fuck.

He remembered so well Coral’s fourteenth birthday, must’ve been November 3, 2001, almost twenty years ago now, wow, and how they’d had a heated discussion about Afghanistan, he couldn’t recall who thought what, both their mouths full of birthday carrot cake; but he could remember thinking, Man, she’s fun, she’s a whole other person now, we can talk, we can discourse. She doesn’t need me so much anymore, she’s independent and free; I’m free. And he’d fallen in love with his child all over again, as if from afar—on her own terms though, even better than that unconditional Hallmark stuff.

But oh how Coral was pissed now that Ridley didn’t want to fawn over her kids’ finger paintings. She didn’t want her kids to experience the same lack of Ridley she’d had. She didn’t say anything like that, but he knew. And because she didn’t say it, he couldn’t say—that’s what their father is for. He couldn’t make up for his lost time with her with them now, could he? There was this ancient . . . diffidence in his daughter he couldn’t quite breach. She seemed to him a collector of minor slights. She harbored things. So now she punished him every chance she could by saying she’d love to see him, his grandkids would love to see him, but they didn’t want to kill him.

He was lonesome now though, lonesome for his daughter. He often felt lonely in life, and then when in company he longed to be alone. He could never figure this out about himself. His desire to be elsewhere. It had surely driven away his wife, hadn’t it? He remembered with hot humiliation an incident where, while introducing his wife of ten years or so at some long-ago stupid party, he’d forgotten her name. He didn’t mean anything by it. He just blanked. There was a black hole in his mind’s eye momentarily where her name usually was, where her name should be. And it wasn’t coming to him. Not fast enough anyway. He had tried to rebound by making it a joke, by making a show of trying to remember, snapping his fingers, one of those mean inside jokes that husbands and wives play on each other to affirm the depth and breadth of their history and secret lives in public (the old ball and chain—what’s her name ho ho ho). And the poor guy at the party had finally chortled uneasily, and Ridley’s wife had laughed to get along as well, but as Ridley swallowed his scotch and shame and looked into her eyes, her eyes weren’t laughing, she was in searing pain, and he was mortified and confused at the dark workings of his own interior; and he knew back then, in that blinding instant, that his marriage was over.

__________________________________

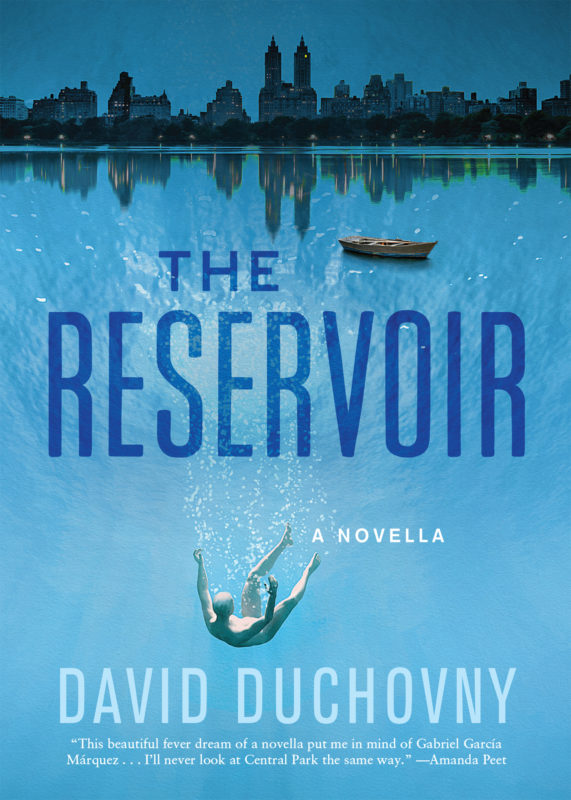

Excerpted from The Reservoir by David Duchovny, copyright 2022 by David Duchovny, used with permission of the author and Akashic Books (akashicbooks.com).