Yesterday evening, I discovered a secret passageway under my bed.

It rumbled like a digestive system running on a forty-two minute, twenty-four second cycle. At its smallest, it contracted to less than two centimeters in diameter, and at its widest, it expanded to between ninety and one hundred centimeters. The soft brown fur covering its interior made it feel dry and squishy like an enormous, velvet-covered hot water bottle.

Pushing my bed to one side, I threw various things in: a broken teacup, pebbles, leftover buttons. Everything bounced quietly down and disappeared. I even lowered a flashlight

on a string to try and see where the hole might lead, but this too proved useless because I couldn’t see past the curves of its fur-lined walls.

I didn’t ask Mother about the passageway. I was curious whether she realized I had noticed it, but still I didn’t ask. I understood the rules: anything Mother did not directly tell me was something I was supposed to figure out for myself.

Turning off my bedroom light, I crawled under my bed and spent an hour staring into the tunnel, which glittered dully under my flashlight. I found myself desperately suppressing a desire to jump in.

I was writing in this diary when Saskia came to visit.

As I hid and locked it away in my safe with the key I keep around my neck, she took dolls out one by one from her pink wagon, along with a Cinderella picture book. The illustrations were splendid, beautiful even, but like all

drawings by people from the planet Mélusine, they contained anatomical errors. Even relatively accurate depictions of human body parts looked slightly awkward when drawn by Mélusinians. This particular illustrator must have wondered why Cinderella’s big toes were attached to the front of her feet and not the back. Perhaps Mélusinians thought the heels on her glass slippers were prosthetic devices designed to compensate for this anatomical flaw.

“I went to the ro-le-kang-ting,” Saskia boasted as she put a new green dress on her favorite doll, Mamarolly. She meant “rolakactring.” This name, seemingly designed to torture the clumsy tongues of children, refers to the playgrounds where Mothers gather together.

I called them playgrounds just now because that’s all we see from our perspective. The only things visible to us in the rolakactring are games and snacks. It would, however, probably be overly naive to assume that the only thing our

Mothers do in them is watch from a distance through the fog as we play.

While I wondered about the true nature of the rolakactring, Mamarolly set off on her own journey. Saskia’s doll games always involve travel: Mamarolly put on a new dress, packed her bags, and headed out to meet all sorts of animals before returning home. Saskia acted out the part of Mamarolly in her nasal voice while I played make-believe with the other dolls spread out around us. Knowing what I now know, I found it difficult to enter into the spirit of the “Mamarolly game.” The game became hard work and required skillful improvisation.

Mamarolly had just returned to her pink house with a new doll friend when a bell rang somewhere above our heads. Saskia’s Mother appeared. Not through a door, but rather out of thin air, like an origami flower that magically blossoms in water. Saskia’s toys moved neatly back into the pink wagon like a film running in reverse. Giggling, Saskia threw herself at her Mother. I stood up to say goodbye, and Saskia and her Mother went home.

As soon as Saskia closed the door, I sat back down on the sofa and began to count. One, two, three, four, five. As I moved my lips into position to pronounce “six,” my

Mother materialized. She, too, appeared out of thin air like a blooming origami water lily or an exploding firework. I felt her gentle, dry warmth embracing me as I told her about my latest adventures with Mamarolly.

To me, math is an inductive science. In a normal world, kids build pyramids of logic based on the principles of addition and subtraction. I, however, am forced to reconstruct general theories of mathematics from clues scattered throughout the books in our library, all of which were written thousands of years ago by my ancestors. None of this is easy. Most of the books I possess are fiction; I don’t have even a single textbook on basic arithmetic.

Nonetheless, I have managed to become fairly competent.

I can do calculus, I understand the concept of double-entry bookkeeping, and I am stumbling my way through trigonometry one theorem at a time. I also know how to apply this painstakingly accumulated knowledge to the real world. Once, when I went with Mother to a huge rolakactring on Mélusine, I was able to calculate the planet’s rotation using just my wristwatch and a protractor. Yes, the whole exercise was rendered pointless by the huge clock hanging in the sky behind me, but that didn’t diminish my sense of accomplishment.

I have also accumulated other rules and bits of knowledge that I only partially understand. After reading Abbott’s Flatland, I tried using the concept of the fourth dimension to explain the existence of the Mothers. Of course, I realized soon enough that time-space was much more complex than anything ever depicted by Abbott, but this would be obvious to anyone who’s ever taken a few interstellar trips with their Mother.

I will probably never grasp the true nature of the Mothers.

Just as I am unlikely to ever understand that tunnel to the unknown that appeared under my bed on the second floor.

I often wonder if life would have been easier had I been sold to a lower life form such as the ones on the planet Endril. Those giants with soft gray fur and strong protective instincts could not have provided me with the kind of house and library that I now live in, but at least I would have understood their rough and simple world.

Yet, it was not someone from Endril who noticed me there as I sat in my cage wearing a dirty diaper and waiting to be adopted. Instead, I was chosen by a green-gray flower with a body that constantly swayed like cloth in water. The instant one of her sight organs fixed on my face, the shop proprietor ran over to her. Pressing my ear to the wall, I listened as they haggled in Milky Way Language 42.

“I’d prefer an animal with fur,” the customer said in an unusually clear and vibration-free voice.

“Species without fur are much easier to play with. You can dress them up in different kinds of clothing and sculpt the fur on their heads into different looks.”

“But doesn’t their skin damage easily?”

“If you take good care of it, it should last a lifetime. If you’re still concerned, we also sell cell rejuvenation equipment.”

“I’ve heard that Terrans are violent. Didn’t they drive themselves to extinction? And don’t they sprout patches of fur and begin to stink when they mature? I’ve also heard that their beauty is ephemeral, that their faces distort and grow ugly over time. What then?”

The shopkeeper’s antennae shook as he smiled.

“Ma’am, please. I assure you. I would never sell an unimproved Terran. My models never grow beyond seven years old. After they reach seven, they cease aging entirely. Moreover, their inclination toward violence has been adjusted, so that they won’t even kill insects. They can’t kill. That instinct has been blocked on a genetic level.”

Later, I learned that Terra is the third planet from a yellow star called Sol that’s tucked away in a corner of the second quadrant of the Milky Way. My species had lived there until it went extinct four thousand years ago. Now the planet is a colony of the Salic Alliance. Seven years Standard Time equals just under six Terran years. I learned half of this from the books in the library Mother had prepared for me, and picked up the other half from neighborhood kids. That is the sum total of my access to knowledge. A library filled with Terran novels and pet children who knew no more about the world than I do.

Are we really pets, though? Our Mothers are not Endrilians. I do not believe that they keep us to satisfy maternal instincts. No matter how seemingly full of love their care for us is, no matter if it actually is loving, I know I cannot fully comprehend them. I do not even know how Mothers’ physical bodies exist on this world, so how could I possibly understand their feelings?

Even pet dogs know more than I do. They at least understand that they belong to a human and are loved. I, however, do not have the slightest idea what my role here in this artificial world is supposed to be.

Yesterday, I got into a fight with Saskia. I don’t even remember why, but even if I did, I still wouldn’t have really understood. Probably one of my dolls misbehaved toward Mamarolly, or perhaps I said something blasphemous about the Mothers and rolakactring.

Before I realized what I had done, Saskia threw a pencil case at me in a fit of anger. This over-stimulated her violence control nerves, so she began to cry and scratch herself all over with her fingernails. Scared, I rushed to get the banana-flavored medicine from the cupboard and spooned it out to her. Once she had finally calmed down, she wiped her tears, collected her dolls, and went home. The Rin Tin Tin movie we had been watching continued to play noisily on the screen hanging from the wall.

I waited for Mother to scold me. She never has, but every time I make a childish mistake, I still anticipate some kind of punishment. It’s funny in a way, because what would be the point? It’s not as if we are ever going to grow into better adults. I am and always will be six years old. My physiological age does not reflect the time I have spent alive.

Saskia does not seem to realize this fact. To her, we are the same age. The adults will always be “Mothers,” and we will always be “children.” The thirty-four years I have actually lived mean nothing to her.

As soon as it became clear that Mother would not be scolding me this time either, I began to prepare my escape. I packed my picnic bag with ten jars of jam and ten cans of food, filled the space between them with clothing and underwear, and hid the bag under my bed. While Mother prepared dinner,

I improvised two ropes out of hand towels. I tried not to think about the real nature of the tunnel or whether Mother suspected anything. Instead, I focused on the details of my plan.

That night, after Mother left my room, shutting the door behind her, I pushed my bed aside and shone my flashlight into the tunnel. It was expanding and contracting as always, its soft velvet surface writhing. While I was waiting for one of its contraction cycles to finish, I tied one end of my towel-rope to my bed and the other end to my bag of supplies. When the entrance began expanding again, I tossed my bag into the tunnel, secured a second rope to my waist, and slowly climbed down in.

The first five meters were fairly steep, but nothing I couldn’t handle. After another five meters, the slope flattened out enough to crawl along without needing to hold onto the rope. Once I reached the end of my rope, I untied my bag, swung it onto my back, and continued downward.

I crawled along in this manner for about another hundred meters. No, maybe it was less than that. It’s my body—I tend to overestimate distance and weight. I blame this on books. I’m so used to reading stories with adult protagonists that it’s difficult for me to remember how much smaller I am than them despite being thirty-four-years old.

The tunnel curved gently at first, but twisted more and more the farther I went into it. I often couldn’t tell whether I was crawling along the floor or the wall or the ceiling. It felt as though each bend in the tunnel caused gravity to pull in a slightly different direction.

The end of the tunnel flared out like the bell of a trumpet.

It seemed to be opening upward, but I could not actually be sure. Murky fog obscured my view, but what I could see beyond the exit looked less like sky and more like green ground about ten meters distant.

As I continued gazing out through the fog, I realized that some kind of dense green netting blocked the tunnel exit. The thick green strands were the size of my index finger and reminded me of a story I had once read called “Jack and the Beanstalk.” The tendrils looked like the limbs of some unknown lifeform. I reached out to touch them and discovered the netting was just as furry, resistant, and soft as the walls of the tunnel. The moment I touched the netting, I felt my body grow lighter. It was as if I had entered a weightless zone where the gravity inside the tunnel negated the gravity outside. Grabbing ahold of the netting, I pulled myself forward until my head stuck out of the tunnel. A light gravitational force tugged at my head.

Unfamiliar green life forms filled the space outside. Some were shaped like starfish and moved quickly; others were spherical and stationary like hot air balloons. From what I could tell, they seemed to co-exist in relative harmony.

I felt vertigo looking down at all this, but it wasn’t because of acrophobia. My vision and sense of balance was thrown off by the absurdity of a world that did not obey the laws of perspective. What I had initially thought were green objects, were actually holes in the light green space.

I stared out from the tunnel for about ten minutes, hesitating. The netting appeared solid, and the green life forms did not look particularly threatening. If I could make good use of the weightless zone, I should be able to orient myself enough to get down there. But was the ground I was aiming for actually ground? And even if it was, what was I planning to do once I got there? And then what?

I turned around and started crawling back home.

Mother said nothing about what I did yesterday, even though I pushed my bed to one side to expose the hole and spread my bag and hand-towel ropes on the floor for her to see. By the time I returned to my room after breakfast, she had cleaned it all up and put everything back in its place, her entire body swaying with laughter as always.

Saskia came over to our house again while I was in the midst of stacking blocks. She clutched a small box, clumsily tied with a ribbon, and as soon as she entered the room, she held it out to me shyly. I untied the ribbon and looked inside. The box contained a hand-knit, or at least seemingly hand-knit, doll sweater.

The apology gift must have been Saskia’s own idea. The Mothers never force moral choices on us. We need only to observe the rules of etiquette already implanted in us, which in any case did not include sacrifices such as this. Was the child maturing mentally? Perhaps. But that wasn’t going to change anything.

Like a good elder, I accepted Saskia’s present and hugged her to show I had no hard feelings about her temper tantrum the day before. Saskia began to cry as soon as my arms encircled her. Surprised, I stepped back to take a good look at her. I could read fear, anger, and above all loneliness on her face. For just a moment, she looked far older than six. I suddenly grew curious about her age. Although I’ve always assumed she was only six, I can’t think of any reason why she couldn’t be older. She behaves like a six-year-old, true, but so do I.

“Shall we play Mamarolly?” I asked timidly.

Saskia nodded and began dressing Mamarolly with her clumsy hands, while I laid out my dolls on the carpet and prepared for a new adventure. An adventure about a fantastical world in which Clairvoyant Bear and Crazy Rabbit could travel anywhere they wanted through a magic carpet tunnel.

__________________________________

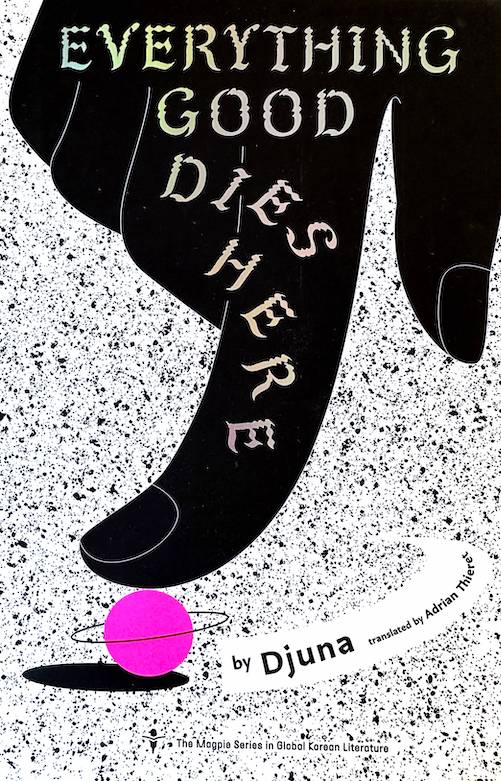

From Everything Good Dies Here by Djuna. Used with permission of the publisher, Kaya Press. Copyright © 2024 by Djuna. Translation copyright © 2024 by Adrian Thieret.