“The Question Project.” On John Dunton and the World’s First Advice Column

Mary Beth Norton Explores the 17th-Century English Origins of a Major Cultural Phenomenon

The publication that initiated the world’s first personal advice column did not begin with that aim in mind. Rather, its founder, the printer John Dunton, envisioned a series of inexpensive single pages (broadsheets) printed on both sides, the eclectic contents of which would be supplied by questions from readers, with responses from Dunton and his associates. The successful venture—the Athenian Gazette, or Casuistical Mercury, known more succinctly as the Athenian Mercury—eventually published thousands of inquiries and replies on a wide variety of topics.

But at the instigation of its readers it also developed into a source of published advice on personal matters, the world’s first. And it became the longest-lasting periodical in seventeenth-century England, its popularity at least partly a result of its public attention to private questions.

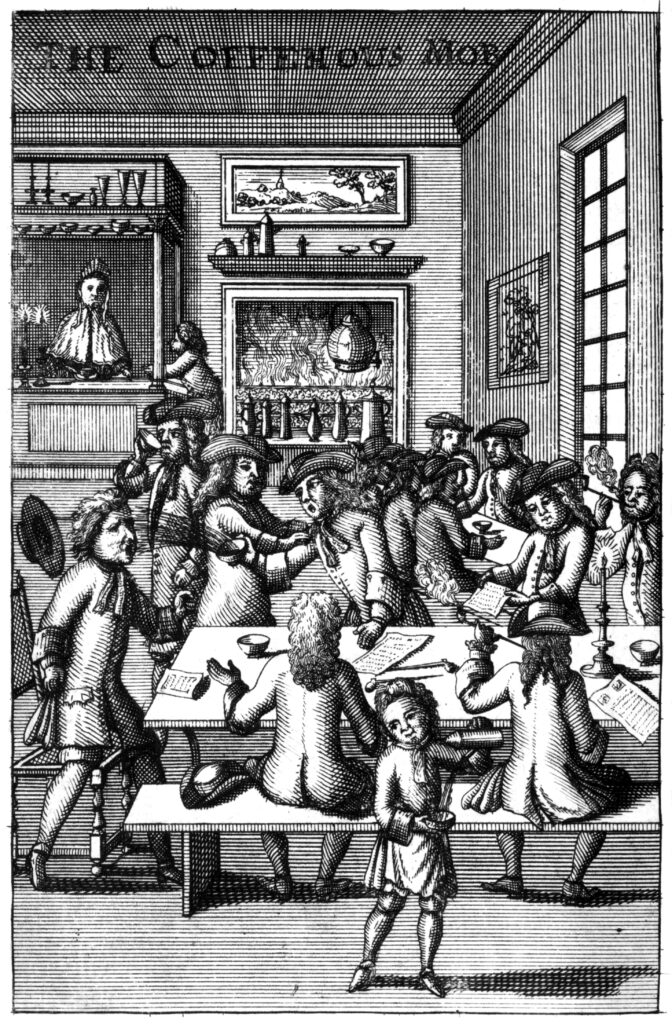

Dunton later recalled that he was walking in a London park with a friend one day in the early spring of 1691 when the idea for such a publication suddenly occurred to him. In retrospect, the premise seems simple, but in its own day it was unique. Dunton proposed a weekly broadsheet periodical aimed primarily at the male patrons of London’s many coffeehouses. Those men, known for wide-ranging discussions held over the new-fangled drink, would pose questions anonymously; the Athenian Society, supposedly a large team of experts but essentially comprising Dunton and his two brothers-in-law, Richard Sault and Samuel Wesley, would answer them.

Without intending to do so, and wholly in response to queries posed by their readers, the Athenians had initiated the first personal advice column ever published.

Dunton, then 32, was a bookseller with eclectic interests; Sault, his initial collaborator, was a part-time mathematical tutor; and the 29-year-old Wesley, whom they quickly recruited to join them, was a struggling clergyman and writer who probably welcomed the chance to earn extra income. Dunton, Sault, and Wesley drew up a formal contract for what Dunton called “the question project.”

Sault and Wesley agreed to draft answers to questions Dunton supplied, to meet each week to go over them, and on Fridays to submit sufficient copy for the next week’s issues. Dunton could then alter or reorder that copy as he wished. For their work, he promised to pay the two men together ten shillings a week after publication (the equivalent of approximately $140 in 2020 dollars). The broadsheets sold for a penny each to individual purchasers and by subscription to coffeehouses. Dunton at first concealed his involvement, identifying himself only as the Athenians’ “bookseller.” Letters were to be sent to a coffeehouse rather than to his print office, and Dunton did not publicly identify himself as the Mercury’s printer until many months had passed.

Dunton’s project met with immediate success, developing into a major cultural phenomenon that spawned several rivals and even a parody in the form of a play, “The New Athenian Comedy.” The first call for questions on 17 March 1691 elicited such a plethora of queries that his initial plan quickly expanded to appearing twice weekly, on Tuesdays and Saturdays. Each broadsheet included eight to twelve questions and answers, or fifteen to twenty in a typical week.

After twenty issues had appeared, Dunton bound the ephemeral one-page two-sided sheets into large volumes that his “Mercury women”—recruited from ubiquitous street vendors—hawked to coffeehouse owners for two shillings sixpence (about $35 in 2020 dollars), contending that customers would enjoy perusing them while chatting over hot beverages. The bound volumes contained indexes, allowing people to locate and read topics of interest in back issues, which in turn elicited more questions and helped to ensure the publication’s continuation.

Eventually, Dunton produced twenty volumes, the last of which included only ten numbers (rather than the usual twenty, plus frequent supplements), because the final period of publication included a months-long hiatus that followed the death of his wife. A few years later, beset by financial difficulties, he sold the copyright to another printer, Andrew Bell, who produced a three-volume compilation titled The Athenian Oracle. In that version, the Mercury’s contents remained available to readers even into the nineteenth century.

The questions, which Dunton anticipated as a coffeehouse habitué himself, ranged widely over many subjects. Among the inquiries were some on the Bible (Who was Cain’s wife? Did Adam and Eve eat actual apples?), science (What is a star? Why does a dolphin follow a ship until frightened away?) medicine (What causes smallpox? Can a crooked person be made straight again?), military tactics (Is it better to attack an enemy’s country, or to guard one’s own?), and law (If a man dies, does his apprentice have to serve the widow?). The three men occasionally consulted others for expert opinions, but their contract forbade additions to the team, and no one else ever formally joined their enterprise or participated more than sporadically. Dunton had created a source where coffeehouse patrons could find answers to questions that arose in their discussions or ask additional ones not previously dealt with in the Mercury.

The Coffeehouse Mob (Collections of the Huntington Library, San Marino, California)

The Coffeehouse Mob (Collections of the Huntington Library, San Marino, California)

The Athenians tried to eschew politics, since the topic was especially fraught after a dramatic change of government two years earlier. In 1689, Protestant Members of Parliament had ousted the Catholic Stuarts from the English throne, formally concluding decades of turmoil that had begun in the 1640s with civil war between Parliament and the Stuart monarchs. The Protestant Mary II and her Dutch cousin and husband, William of Orange, jointly assumed the throne in 1689, but their rule was still contested by many supporters of the Stuarts.

Even after 1695, when Parliament’s 1643 censorship law for “correcting and regulating all abuses of the press” was allowed to lapse, Dunton tried to avoid including political opinions in the Mercury, other than broadly supporting the regime of William and Mary. A several-month suspension of publication during 1692 caused by a communication that ran afoul of the censors taught Dunton an important lesson that stayed with him for the rest of the decade.

After just a few weeks, the publication’s anonymous correspondents began to broach a theme that the three men had not anticipated: inquiries about personal relationships, including courtship, marriage, and sexual behavior. The first set of such questions—thirteen in all—came from a man; the Athenians printed them and their answers in the thirteenth issue in early May 1691. Those queries were broadly and impersonally phrased: for example, should a person marry someone they “cannot” love in order to gain access to a good estate? Don’t most people marry too young? Is a woman worse off in marriage than a man?

In the same issue, the Athenians noted another unexpected development: “a lady in the country” had written to inquire “whether her sex might not send us questions as well as men.” Dunton’s initial publication plan centered on an exclusively male audience, for only men frequented coffeehouses, although some women worked in them. That letter surely surprised Dunton and his colleagues, not only because it came from “the country” instead of London, but also because it was from a woman, who must have accessed the Mercury through a male relative or acquaintance. Yet the Athenians adapted quickly, explaining that they would “answer all manner of questions sent to us by either sex.”

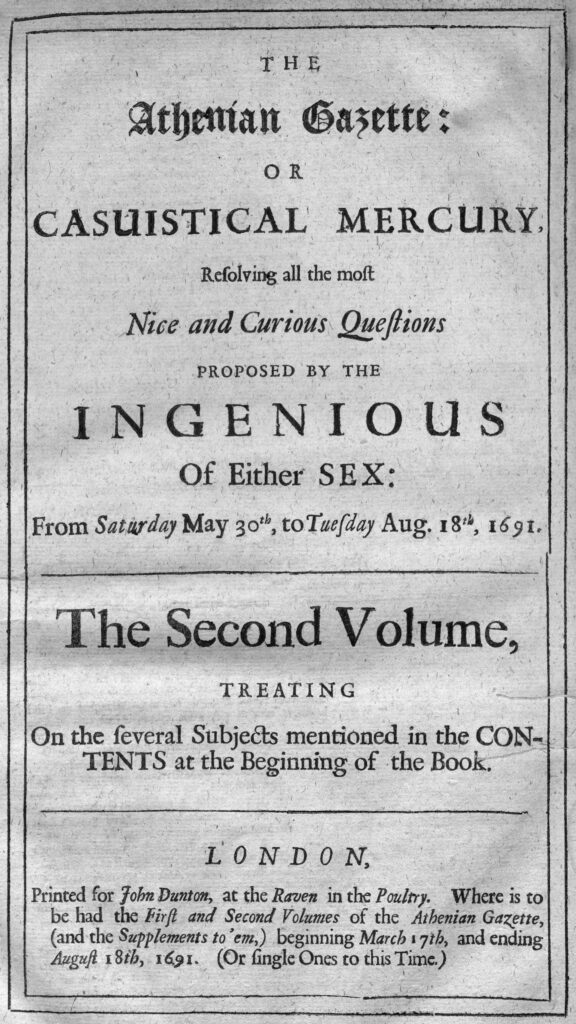

Accordingly, a few weeks later a woman submitted a similar group of impersonally phrased questions (for instance, is it proper for women to be learned? is beauty real or imaginary?), which the Athenians answered in their eighteenth issue in late May 1691. The next month, at the end of what became the first bound volume, they responded to the first explicitly personal query they received—from a man accused of fathering a child out of wedlock (included in the selections in this book, along with several other examples of the initial questions). And so, when Dunton gathered the broadsheets to create the second volume, he changed the title page to reflect openness to female as well as male querists, as he termed those submitting questions.

Title page of the second bound volume of the Athenian Mercury (Division of Rare and Manuscript Collections, Cornell University Library)

Title page of the second bound volume of the Athenian Mercury (Division of Rare and Manuscript Collections, Cornell University Library)

Without intending to do so, and wholly in response to queries posed by their readers, the Athenians had initiated the first personal advice column ever published. Anonymity was clearly the key: concealing the identity of correspondents formed a part of Dunton’s conception of “the question project” from the outset. A survey of a randomly selected volume (six, published in early 1692) by the scholar Helen Berry revealed that nearly one-third of the more than two hundred inquiries in that volume fell into the category of questions about personal relationships. Dunton often grouped such queries from both men and women into “ladies issues”; in the first five volumes, 45% of those inquiries came from men and 23% from women; 33% were not identifiable by gender.

The questions…open a remarkable window into the private lives of men and women in an era long before our own.

Although the Oxford-educated Wesley was the only formally trained cleric in the group, Dunton was the son and grandson of ministers, and the three men shared a broadly based Protestant outlook. They aligned themselves with the campaign for the Reformation of Manners, a movement led by Queen Mary II that sought to combat perceived excesses of the day, especially prostitution and clandestine marriage. Themes of religion, sexuality, and morality were entwined in the minds of both the Mercury’s readers and the Athenians themselves. Their responses to correspondents who described various types of sexual misbehavior rarely expressed sympathy for questioners’ plight but instead frequently decried the immorality involved. Yet occasionally even in such instances the advice offered was judicious and must have been welcome.

One anonymous reader, after perusing broadsheets that contained what they termed “pitiful” personal inquiries, charged the Athenians with detracting from the publication’s learned reputation by dealing with such matters. But Dunton and his colleagues insisted on the importance of the topics their correspondents raised. “Many questions not only have an influence on the happiness of particular men and the peace of families, but even the good and welfare of larger societies and the whole commonwealth, which consists of families and single persons,” the Athenians commented [3:13, 8 September 1691]. So, ignoring the pointed criticism from at least one member of their audience, the Athenians continued to offer personal advice to those who asked for it. And many continued to ask… for the next six years.

The questions, whether accurately representing the correspondents’ own experiences or not (some said they were writing on behalf of “a friend,” which the Athenians often explicitly recognized as a fiction), open a remarkable window into the private lives of men and women in an era long before our own. Even though the queries often formally referred to the problems of “gentlemen” and “ladies,” their content reveals that the authors were not for the most part drawn from the ranks of the very wealthy but instead had middling status or aspired to upward mobility.

Many, though by no means all, were young, just starting out in marriage or a trade. They confronted all the problems common to that stage of life, including conducting courtships, acquiring property, and engaging in premarital negotiations. In an era in which literacy was increasing significantly, especially in the ranks of urban tradesmen and tradeswomen, reading and writing were no longer optional but required skills for those who hoped to improve their lot in life.

__________________________________

From I Humbly Beg Your Speedy Answer: Letters on Love and Marriage from the World’s First Personal Advice Column by Mary Beth Norton. Copyright © 2025. Available from Princeton University Press.

Mary Beth Norton

Mary Beth Norton is the Mary Donlon Alger Professor Emerita of American History at Cornell University. Her books include the Pulitzer Prize–finalist Founding Mothers & Fathers: Gendered Power in the Forming of American Society; 1774: The Long Year of Revolution, winner of the George Washington Prize; In the Devil’s Snare: The Salem Witchcraft Crisis of 1692; and Liberty’s Daughters: The Revolutionary Experience of American Women.