The Pugnacious Outlaw Women Behind My Protagonist

From Hellcat Maggie to the Great Sandwina, Eight Women Who Defied Their Era

Alma Rosales, the main character of my novel The Best Bad Things, is a muscle-bound, butch, pugnacious private detective who loves to start trouble. She prefers trousers to skirts. Her favorite pastimes are brawling and sex. She would be at home in a present-day crime drama—yet her story takes place in 1887. This was the height of the Victorian era, when the popularized expression of womanhood was very different than Alma’s take on it. But she’s not as out of place as she might seem. Her character is rooted in historical precedent: there have always been female athletes and outlaws and rule-breakers. Bareknuckle boxers and strongwomen shocked people with their physical abilities. Women (and men) risked arrest to wear the clothes that suited them best. Still other women broke the mold of “female delicacy”—along with the law—by engaging in violent crimes. Here are a few of the formidable folks who helped me shape Alma’s character.

Elizabeth Wilkinson Stokes, bareknuckle prizefighter

Stokes was a boxer in 1720s England. Female fighters were not so uncommon; in the ring or in semi-organized street fights, women fought for money, clothes, or other prizes. They often fought stripped to the waist, and the smaller, scrappier contests involved biting and scratching. Stokes was notable for her string of victories. Also notable is that she used the “half-crown rule” in her fights, which stipulated that the boxers had to hold a half-crown in each of their fists, and the first woman to drop a coin lost. This rule prevented the fighters from resorting to the scratching and eye-gouging that was common in rougher bouts, and kept the focus on the fighters’ punches, skill, and stamina.

Documentation of Stokes’s biggest fights has survived in the form of her challenges and responses—calls to fight issued by boxers via printed notices in the papers. Often taunting in tone, these challenges capture Stokes’ swagger and salty wit; she concludes one response (to challenger Ann Field, an ass-driver) with: “as the famous Stowe Newington ass-woman dares me to fight her for the 10 pounds, I do assure her that I will not fail meeting her for the said sum, and doubt not that the blows which I shall present her with will be more difficult for her to digest than any she ever gave her asses.”

Laverie Vallee, aka Charmion, gymnast and trapeze artist

Vallee rose to fame as a performer in the 1890s. Her best-known routine was a combination of burlesque and acrobatics: she would start off the performance in full Victorian dress and then, while perched on the trapeze, strip down to a bodysuit. This routine was called the “Trapeze Disrobing Act,” and was the subject of one of the earliest short films (shot by her admirer Thomas Edison); this footage is still available to watch. In addition to her gymnastic skills, Vallee was remarkable for her athletic physique. Promotional photos show her in performance attire, displaying back and biceps muscles that are impressive even by today’s bodybuilding standards.

Jeanne/Jean Bonnet, pickpocket and man about town

Bonnet lived in San Francisco in the 1870s. Their pronouns are not known; some modern accounts identify Bonnet as a trans man, while others identify them as a lesbian. Bonnet had frequent run-ins with the police, not just because of instances of petty theft, but also because they frequently wore men’s clothing. (At the time, cross-dressing was an arrest-worthy offense.) Bonnet often visited brothels as a customer, and some histories allege that they recruited former sex workers to leave these bordellos and join their growing gang of female thieves. Bonnet was murdered while with their lover, and was subject to censure even after their death. The San Francisco Chronicle published this in the wake of the murder: “Her career and fate furnish an illustration of the difficulties under which women labor when they undertake to disregard the conventional rules which are popularly regarded as constituting the law for their sex.”

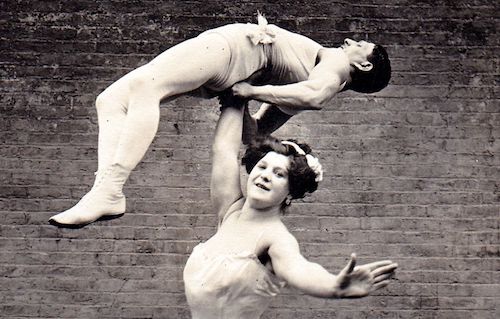

Katie Brumbach, aka The Great Sandwina, and Josephine Blatt, aka Minerva, weightlifters and vaudeville strongwomen (pictured here is Brumbach, lifting her husband)

In the 1890s and early 1900s, the heyday for strongwomen, Brumbach and Blatt were two of the most famous performers for both American and European audiences. Brumbach came from a circus family and quickly progressed from wrestling feats to those of strength. In one notable contest, she bested popular strongman Eugene Sandow by lifting 300 pounds overhead with one hand (a feat Sandow could not match). Her performances often featured her bending iron bars, juggling cannonballs, and lifting her husband overhead. Blatt has a murkier family history, but she appeared on the strongwoman scene in the 1890s and immediately started issuing challenges to rivals (and winning). For a time she was in the Guinness Book of World Records for the most weight ever lifted by a woman. To fuel her strength, Blatt told the San Antonio Daily Light in 1892, her diet was a protein bonanza: “For breakfast I generally have beef, cooked rare; oatmeal, French-fry potatoes, sliced tomatoes with onions and two cups of coffee. At dinner I have French soup, plenty of vegetables, squabs and game . . . When supper comes, I . . . have soup, porterhouse steak, three fried eggs, two different kinds of salads and tea.”

Hell Cat Maggie, Sadie the Goat (pictured), and Gallus Mag, New York criminals.

Following the Civil War, New York City saw an increase in population and in crime. In addition to the mostly male gangs that ran the Bowery (the Plug Uglies, Bowery Boys, Whyos, and more), there were some fearsome women with reputations for mayhem. Hell Cat Maggie is reputed to have sharpened her teeth to points and donned brass fingernails shaped like claws. According to Herbert Asbury’s Gangs of New York, a 1928 compendium of New York’s criminal history, Sadie the Goat got her name as follows: upon sighting a wealthy looking target, she would head-butt him in the stomach, and while the victim was stunned Sadie’s companions would beat and rob him. Sadie was also a river pirate whose gang wreaked havoc along the Hudson. Gallus Mag worked at the Hole-in-the-Wall saloon. She was six feet tall and incredibly strong. According to Asbury’s account, if a man caused trouble in the bar, Gallus Mag had a habit of biting him by the ear and thus hauling him to the door; if he resisted she would chomp his ear off. The Hole-in-the-Wall displayed a collection of ears kept in a pickling jar as the result of Gallus Mag’s efforts.

These historical figures run the gamut from awe-inspiring to dreadful, but together they present a wide scope of alternatives to the stereotype of the dainty Victorian lady. (Of course, wealth was a major requirement of this stereotype; working-class women were cleaning, cooking, and laboring at a time when such tasks required much physical strength.) I drew upon their athleticism, love of combat, and criminal daring to build Alma’s character. In reference to Bonnet’s story in particular, I wanted to use The Best Bad Things as an opportunity to upend the “tragic downfall” narrative often placed on queer folks, and reframe a queer outlaw as hero and survivor. With Alma, I wanted to create a singular powerhouse of a character—queer, tough, proud, and hard to pin down as she plays both sides of a criminal investigation. As Alma herself might phrase it, she’s a protagonist who’ll show you a good time like you’ve never seen.

Katrina Carrasco

Katrina Carrasco holds an MFA in fiction from Portland State University, where she received the Tom and Phyllis Burnam Graduate Fiction Scholarship and the Tom Doulis Graduate Fiction Writing Award. Her work has appeared in Witness magazine, Post Road Magazine, Quaint Magazine, and other journals. She is the author of the novel The Best Bad Things.