The Northeast Nevada Regional Bookmobile

by Kelvin K. Selders

I am the librarian for the Northeastern Nevada Regional Bookmobile. You could say that I’m the driver of a 2005 Kenworth filled with books, but the job requires more than driving.

Many of the places I stop at are very remote. “Remote” in Nevada means hours away from a town big enough to have a library. When the stop is closer to a town or a school library, we offer convenience to our patrons. It is much easier to bring a class of students to a library when it is parked beside the school. We also offer books and information on request.

The most essential aspect of my work is getting the books into young hands. The younger they start, the better. Children need to be exposed to print and books in many different capacities before they enter school. Most children can load a VCR tape or DVD and push “play” on the remote before they know “a is for apple.” You will never get a diploma watching videos. You need to obtain reading skills to maximize your education.

* * * *

Ruby Valley, Nevada, 9:30 to 10:30 a.m., every other Monday: It takes me an hour and twenty minutes to drive from Elko to the school at Ruby Valley. I cross the Ruby Mountains at Secret Pass. The road has many curves as it climbs through the pass. You can see a stream flowing far below, feeding the trees and shrubs.

The first patron I see at Ruby Valley is Ben Neff. He is a thirtysomething with special needs, and usually has about five watches on one arm. He collects uniforms and name tags and is usually wearing his latest one. Ben has a problem with stuttering, but he does one thing well: he can read! I park at the Neff Ranch in the summertime. A lot of the locals are related to the Neffs, so it’s like meeting at Grandma’s house. During the school year, I park at the school.

I often see patrons waiting for me when I get there, and when the steps are locked down and the generator is started, the schoolkids come out. Have you ever seen a child running to get a book? I have, and it makes me feel my job is worth more than the money I make. Parents with small children, even babies, come out at the same time as the schoolkids. In the six years I’ve been working at this job, I have watched some of the kids grow up, and now they have their own library cards and are students at the school. While I am there, the patrons usually visit with each other and discuss books they have read. The Ruby Valley stop is more of a “family community” stop.

* * * *

Montello, Nevada, 1:00 to 2:00 p.m., every other Monday: It takes me an hour and a half to drive from Ruby Valley to just outside of Montello. I stop for lunch in a remote location—so remote that there’s no radio signal, not even AM. I try to pull into the school at Montello five minutes early. There are patrons waiting.

When I started driving the bookmobile, this stop had three kids from the school, the teacher, and the lady next door. Now I have most of the adults in town, along with the schoolkids. Of all the places the bookmobile stops, Montello needs it the most. I can understand poverty—that’s the way I grew up, although Montello is a lot smaller and poorer than where I came from. The children have a playground at the school—a swing and a slide. The adults have a small store and a bar. I heard they finally got a cell tower up, so the better-off people can have a cell phone. If they have a computer, they get online through a dial-up connection. One patron with no power or water on the property hauls water and uses candles. This patron does have a portable CD/DVD player to watch movies and listen to books on CD, but can only use it in the pickup truck.

I noticed a problem on the bookmobile when I first started working. Some of the kids would leave without a book in their hands. This was happening because they did not have a library card and neither did their parents. It takes two weeks to get your library card, unless you go into the main library at Elko.

We started stocking paperbacks, which kids can check out without a library card. We have easy-to-read books for the smaller kids. Some are even chewable board books. We also have juvenile books for the older kids and adult paperbacks. Now no one has to leave the bookmobile without a book. That should be a librarian’s primary job: to get books in people’s hands.

Kelvin K. Selders was born in 1957. He has been a paperboy, farmhand, U.S. Army mechanic, Dodge mechanic, truck stop attendant/labor and training manager, carpenter, tire man/sales and service manager, driver, and, for the last seven years, the Northeastern Nevada Regional Bookmobile Driver for the Elko-Lander-Eureka County Library System. He has an associate’s degrees in Mechanics, Networking, and Information from Great Basi College in Elko, Nevada.

Slideshow: The Public Library, photographs by Robert Dawson

- Central Library, Seattle, WA 2009 Dutch architect Rem Koolhaas and Joshua Ramus were principal designers for this library that opened in 2004.

- Library built by ex-slaves, Allensworth, CA.1995

- Redwoods, Mill Valley Public Library, Mill Valley, CA 2012

- Storrs Library, Longmeadow, MA 2011

- Library, Roscoe, SD 2012 The library was built in 1932 in the small town of Roscoe, ND by a group of civic-minded women called the Priscilla Embroidery Club. The land for the library was donated and the women hauled the rocks for the chimney and foundation while their husbands constructed the building. Approximately 1,500 books were in the library when it closed in 2002.

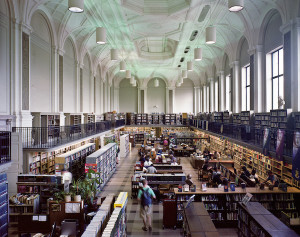

- Reading Room, Central Library, Free Library of Philadelphia, Philadelphia. PA 2011

- Northeastern Nevada Regional Bookmobile, Elko County Library, Baker, NV 2000. This bookmobile stops at 29 locations every two weeks. It serves a vast area of rural northeastern Nevada, one of the most remote regions in the 48 states.

- McCoy Memorial Library, McLeansboro, IL 2012

- Sculpture, cliffs and Springdale Branch Library, Springdale, UT 2012

- Yarborough Branch Library, Austin, TX 2011 This branch library is housed in the former Americana Theater building.

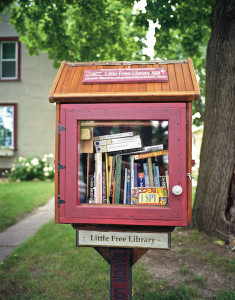

- Richard F. Boi Memorial Library, First Little Free Library, Hudson, WI 2012, Little Free Library is a community movement started by Todd Boi and later by Rick Brooks. Todd started the idea as a tribute to his mother, who was a book lover and school teacher. He mounted a wooden container designed to look like a school house on a post on his lawn. The day I photographed this first Little Free Library Todd opened the door and it began to play “To Dream the Impossible Dream.”

Practicing Seva

by Dorothy Lazard

I’ve been thinking about my grandmother a lot lately. When I was ten and living with her, she ran a board-and-care home for adults with psychological problems. As the only child in the household, I was recruited into service. I didn’t know then about schizophrenia, obsessive-compulsive disorders, or any other ailment that might land someone in a “rest home” (as they were called back then), but I would certainly learn. My job was to look after this strange band of inmates while my grandmother ran errands or went to church. It was not hard work—just work I didn’t want to do. Like cutting the crusts off of Phyllis’s sandwiches. (Crusts sent her into conniptions.) Or making sure Akiko had her phenobarbital with each meal. Or allowing chattering Gloria to tread a rut in the hallway hardwoods. At the time this all seemed a waste of a good childhood.

Little did I know that I was learning patience, compassion, and stamina in that first unwanted position. All these skills have come in handy in my job at the Oakland main library. When I arrived there more than a decade ago, I was reintroduced to the same types of characters—the biochemically imbalanced, undermedicated, traumatized, inebriated, and drug-addled—only multiplied exponentially.

“How you say this name,” a man at the desk asked me, squinting at the encyclopedia in his hand, his face a couple of inches away from the page.

“Kwame Nkrumah,” I said.

“Kwame Barumba.”

“No. Kwame Nkrumah.”

The man looked at the entry again. “He was the first president of Ghana.”

“Yes. That’s right.”

“How you say his name again? Kwame Mtumba.”

“No. Kwame Nkrumah.”

“Lumumba?”

“No. That’s someone else.” I pointed to each syllable of the name. “N-kru-mah. Kwame Nkrumah.”

“Nkrumah.”

“Yes!”

“Kwame Larumba.”

I shrugged a little as he walked away from the desk. I usually let him go on like that because his inability to hold Nkrumah’s name in his head is a minor issue. I know that

toward the end of the month, when some demon has him by the collar, when his money—and, perhaps, his medication—has run low, he will come in, spewing a litany of curses at some phantom tormentor. And one of us behind the desk will calmly say, “Sir, please watch your language,” as if he is in control of his language or his mind or his life.

Other encounters are more sinister. Patrons threaten the library staff and each other with physical violence. They argue for physical space at the reading tables, extra time on public Internet terminals, and staff attention. When the doors open we welcome all manner of demands, crises, and strange behaviors.

Providing service to the homeless and untreated ill in California has been a steadily growing public-service challenge. Back in 1969 the passage of the Lanterman Act forced the closure of several large psychiatric hospitals. The argument for these closures was the high cost of maintaining them. The establishment of smaller, community-based facilities couldn’t keep pace with the vast number of displaced patients. Over the next two decades, closures continued. As a result, the homeless and mentally ill population in urban areas exploded. Many patients returned to families ill-prepared to care for them. Others were arrested, becoming part of the prison system. And still others took their chances on the streets, seeking some form of independence. Many of them turned to self-medicating with drugs and drink or opted to live undiagnosed and unmedicated. Over the last thirty years, as a result, the public library has absorbed them.

As the last truly democratic space in America, where there are no entry fees, judgments, or barriers, public libraries offer a tour of our society’s ills and ill. We library workers are, in practical terms, surrogates for shuttered schools, parks, hospitals, and homes. And we know we are hopelessly unqualified to treat what ails many of the people who pass through our doors. We are practicing a form of seva, the Sikh notion of selfless service. There is deterioration all around us, yet we carry on, providing service to the underserved, a patient ear to the unheard. We are acting as the last outposts of community space.

This is not a rosy picture, but neither is the situation. It’s actually cause for alarm and action. Yet the public alarm seems to be on “pause.” It’s easy to find people who have abandoned their libraries altogether because of the number of homeless and mentally unstable individuals one finds there.

As a taxpayer-supported institution, the library doesn’t have much choice but to let everyone in. The homeless and mentally troubled have as much right to be here as any Montclair nanny or Melrose hood-rat. Very hard decisions will have to be made if—and this is a very big if—ever there arises a movement to boot them out of the libraries. Sure, we have protocol for how to remove people from the library who cause disturbances: if they foul the floors, threaten us or other patrons. But we don’t have the skills or resources to cure them. We can provide them with routine; a warm, relatively safe place; and a wealth of materials that, I hope, steadies their minds. By latching onto something—sports statistics, movie trivia, war histories, art books—they can anchor themselves to this shifting craft we call reality. At least for a while.

They ask us about UFOs. They boast of killing Lincoln. They shuffle rows of shelved books. They want to argue Bible passages and find out how much Indian blood they have. They tell us to hold all their calls and to reschedule their appointments. And we dutifully ride the wave of incomprehension, waiting for a moment of clarity to arrive so we can deliver the information they requested. Yes, I know—to believe that our efforts are not in vain is a form of magical thinking. But it’s an occupational hazard. Librarians are trained to be polite, patient, and helpful, no matter who stands across from the reference desk. The most important thing is that we look them in the eye and take them seriously. Our work demands that we become dreamers, holding onto hope that our society can be better, that we sevadars affirm for our patrons that they are still part of this society, no matter how marginalized they have become in it. I was raised on the notion that the public library is a civilizing institution. And if our work calms someone’s demons or teaches someone else how to treat the mentally ill with respect, then I am proud to be a part of the process.

Dorothy Lazard manages the Oakland History Room, a special reference collection of the Oakland Public Library. Before coming to Oakland Public, she worked for many years at the University of California at Berkeley, where she ran two small campus libraries. She holds a master’s degree in Library and Information Studies from UC Berkeley and an MFA in Creative Nonfiction from Goucher College in Baltimore. Her writing has appeared in a number of anthologies and magazines, and in the librarians’ blog The Desk Set.

From THE PUBLIC LIBRARY: A PHOTOGRAPHIC ESSAY. Used with permissions of the publisher, Princeton Architectural Press. Copyright © 2014 by Robert Dawson.