The Problem With Writing About Florida

"This Isn't Your Place to Write About. It's Barely Mine."

INVASIVE SPECIES

One summer it rained so furiously in Orlando that the roads formed lakes cars couldn’t drive and frogs fucked themselves hoards of children. The retention pond behind my family’s church housed billions of tadpoles, and when those bodies grew legs to migrate landward, frogs found their way inside the church building. They stowed away inside purses and got into discarded sport coats. Frogs crept under the pews and into the nursery, slipping into diaper bags. Slapped flat between the pages of the bible, they lay smashed to death by the hefty weight of scripture.

Boys from our Sunday School class played a terrible game that summer. They asked us: who could open their mouths wider, boys or girls? When a girl opened her mouth to show that she could, a boy tossed a tiny frog inside. Some of those frogs got spit out and others landed between molars, bit down hard after a scream. It was funny for boys to see what they could get girls to swallow. That game went on for months. But then the church called out an exterminator. They sprayed the retention pond with a poison that killed off everything, including the fish and the birds. Church smelled rotten well into September, like meat gone off in an abandoned fridge. Mothers, fathers, deacons: everyone wished to go back to the plague of frogs so we could forget about the dead things out back.

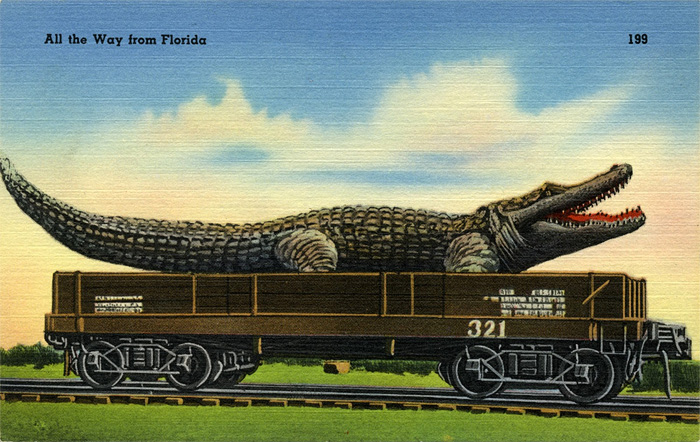

Things die here. Things die and the fecund mess makes way for new, teeming life. All that rot means something new is breeding. Not necessarily something better. Just something different. Something strange and close, adhered to your flesh.

Florida is no place for those who want to view it from a safe distance. This state is invasive, creeping, needy. Hardy and scrabbling, our peninsula’s sour with poison and rot and choking vines. You fight for the right to live in its greenery, and once you’ve finally carved out a space, you stay tangled in the wreck. Once you’ve left, there’s no coming back. The best you can do is hack out a different life somewhere else.

This place isn’t yours to write about. It’s barely mine.

WE DON’T ALWAYS KNOW WHAT WE ARE, BUT SOMETIMES WE DO

Florida isn’t like other states, but you’ve heard that before. Some of what we are is just terrible. We’ve got a lot of crime and racist, shitty cops. People here voted overwhelmingly for Trump. I’m trying to build something new in this essay, but the honest truth is that some of the bad stereotypes are accurate.

THERE LIES ORLANDO

Central Florida has the special significance of being just far enough away from either end of the state that we’re neither Northern nor Southern, but an amalgam of everything. You can drive an hour and reach beaches at either coast. You can get to Disney World in the same amount of time. This is great for tourism and terrible for a sense of place: It means that people call you tacky because your home serves the purpose of entertaining strangers for money.

The history of Orlando includes a fuzzy and unverified account of its naming. Called “Orlando’s Grave,” it’s rumored that the ending was simply dropped for concision’s sake. A place named after a grave is an interesting way to think about where you’re born. Growing up, one of my favorite hymns was Up From the Grave He Arose. It’s a battle cry for Christ’s triumphant victory over death, but it made me think of zombies.

I’ve thought of this undead place in many ways: an abscessed tooth I refuse to pull because I’m terrified of the way my body might choose to atrophy; potato vines crawling inside an air-conditioning unit until the whole thing shuts down and floods the carpet in my shitty duplex; a family of feral blue-eyed cats living inside an abandoned car parked behind a 7-Eleven; the beautiful, contorted face of a rabid animal.

How do I write about the unseen parts? Muck dragged up from the roots of my experiences. Springy Spanish moss hangs from trees like ancient party streamers, close-set palmetto bushes breed 100 slick-backed roaches, the prick of sandspurs digs into my bare feet as I run across a yard. It is pain and pleasure. It’s a taste like mold in the back of the throat. It’s the snow cone shop where the owner throws hunks of ice at the kids while they wait for frozen dollar treats, even in December. Even in January. Even standing in the torrential rain of daily August thunderstorms.

Orlando is wet, sticky, violent. It’s the place where you learn the contours of your body through sweaty shorts and tank tops. It’s a damp, cold bathing suit pulled down around your ankles while you pee in a friend’s bathroom at a pool party.

Here’s what I know: If I don’t love Florida, I don’t love myself.

I have a lot of trouble loving myself.

I watch a storm roll in, palm fronds slapping against each other like excited hands. I’m writing this as the clouds clear and the sun cooks all the wet off the pavement. I am writing this as the weather turns, again and again. Maybe that’s the reason it’s so hard to write about Florida. It never knows what it wants to be. I know this isn’t the kind of place you can write an essay about. Yet here I am.

WHERE SHOPPING IS A PLEASURE

It takes 15 minutes for the people at Publix to build my pub sub, which is 12 minutes longer than any other establishment takes to make a sandwich. But I’d stand in line longer than that if I had to.

THE SMILING BISON

“Strip” is a word often used to describe Florida. We have strip clubs and the long, endless stretches of strip malls that line the roads outside Disney. Sometimes the word is used in conjunction with our coastlines, sadly stripped of their natural resources.

I grew up in a small rental house directly across the street from a topless bar. We faced its backside, and that topless bar faced a larger six-lane highway. Across the highway from that topless bar sat a demolished sewage treatment plant. Summer days of rain and sun brought out air redolent with human waste. You couldn’t leave the house without getting big whiffs of it. It sat abandoned for most of my childhood because nobody wanted to buy property that reeked of shit.

The topless bar didn’t open until dark. My brother and I weren’t supposed to look outside at the people, but once my parents stopped paying attention, I went right for the window. Loud music crossed the street in waves, bass vibrating deep inside my chest. It was a completely different world than the one we lived in. Everyone at the topless bar was having a good time.

Curled up behind the curtain, I watched women bum cigarettes off men sitting behind the wheels of parked trucks. The women wore outfits that only covered their bottom halves: spangly short-shorts and black leather skirts with fishnet stockings. Bathrobes, sometimes. But a lot of the time they wore nothing but skimpy bras up top, crossing their arms over their breasts. Men leaned out their trucks, wanting to get closer, while the women laughed and moved away, cigarette smoke curling overhead as they exhaled.

That parking lot was full of fire ants and broken glass, but often the women yanked off their high-heeled boots to massage their feet. They walked back inside in their stockings, tiptoeing to avoid gravel and tire-flattened bottle caps. I found them graceful and lovely, picking their way across the divide, arms outstretched like tightrope walkers. I couldn’t decide whether I wanted to be like those women or like the men who got to watch them walk away, breasts shivering in the moonlight.

There’s a restaurant there now called The Smiling Bison. When friends invite me there, I always decline. I think what it would be like to look out of that place and see my old house, windows curtained like shuttered eyes. I imagine seeing my former self, and I don’t know what I’d say to that girl, what to tell her about who I’d become or why I’m still in Florida or how I feel about any of it.

Younger me saw those beautiful topless women and stuck her tongue to the mesh to try and taste their difference. Our jalousies held screens to keep out bugs, but they also trapped them inside with us. Dead moths pinned to dusty windowsills, my tongue licking the rusty metal close beside them. Relentlessly pressing my mouth to the world outside, trying to get anything to open up.

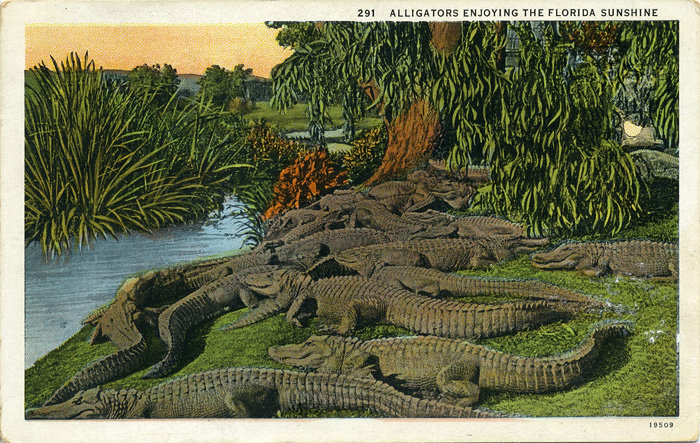

CREATURE FROM THE BLACK LAGOON WAS FILMED HERE

This has always been a place that scares people. I like that about Florida. It means I can act any way I want and know I’ll always be welcome.

WATERING THE LAWN

A hard freeze hit Orlando in 1992. No one here knew what to do with such cold weather. There were no heavy jackets or boots waiting in closets, no gloves or hats or scarves. The school my brother and I attended kept a basket of coats from Goodwill by the front door, handing them out daily to shivering kids who’d worn shorts and t-shirts in 30-degree weather. Our yards were full of plants as conditioned to the heat as we were. Everyone wrapped their trees and bushes in towels and sweatshirts, covering them with bed sheets and praying for warmer weather so their flowers wouldn’t die.

Our neighbors forgot to turn off the timers on their sprinklers. In the early morning hours, water spritzed wildly into the freezing air and ice-slicked everything. When we drove to school, bundled in our cheap, ill-fitting coats, heat blasting, we passed yards covered in dripping diamonds. Every ugly rental house on our street suddenly resembled a winter wonderland. It only lasted a few hours before the sun melted it, but it’s still one of the most beautiful things I’ve ever seen.

ERNEST SAVES CHRISTMAS

In this holiday classic, iconic weirdo Ernest P. Worrell rescues Santa with the help of his Florida friends. As a reward, Santa uses his magic to make it snow in Orlando for a single night. Ernest stands amidst the falling flakes, mouth agape at the spectacle of frozen water. Florida, home of the pink plastic lawn flamingo, suddenly dusted in a classy veneer of purest white.

Finally, a season. Finally Christmas.

It snowed here once when I was young. Microscopic flakes only viewable through the headlights of cars. I stuck out my tongue to catch them, like they did in the Peanuts Christmas special, but the heat of my mouth thawed the ice before I could catch one. I’ve only seen real snow twice in my life and both times it felt surreal, like watching stuffing flung out of a ripped sofa cushion. We don’t have seasons in Florida. We have hot and less hot. A thing kids like to do here is take paper out of shredders and toss it on the floor. If you lie down and spread your arms and legs, you can make a Florida Snow Angel.

Maybe that’s not tacky enough.

I can make it sound worse to keep you comfortable. For instance, if I tell you that the movie Ernest Saves Christmas was filmed here, does it make my affection for Orlando more palatable? Does it make it easier for you to hear that this place is embedded in me, that I wouldn’t scrape it out if I could, if you get to imagine walking punchline Ernest P. Worrell superimposed over my tenderness?

Do you need Florida Man so you’re able to listen to a Florida woman talk about home?

NOBODY ACTUALLY LIKES JIMMY BUFFET’S MARGARITAVILLE BUT TO BE PERFECTLY HONEST THE DRINKS ARE PRETTY OKAY

Listen, I’m never gonna turn down happy hour.

BACKYARD ATROCITIES

My brother and I ate otter pops on the back deck because our mother didn’t ever want us in the house. It’s hot enough any afternoon in Florida that playing outside often feels like punishment. Once the sky tipped to dusky violet, we could go inside for dinner. For kids with nothing to do, summer days are longer than any other kind.

There were kids that lived in the apartments next door and in the houses around the retention pond out back. We weren’t supposed to talk to them, but one day when we were out on our rickety old dock, a group approached us. They were at least two years older than me, and I’m older than my brother by a year. These boys swore and chewed dip. Their t-shirts pouched from where cans sit pocketed at the front of their chests.

Do you wanna see something, asked the oldest. He was holding a pearl-handled knife in one hand and a squirming lizard in the other. Do you wanna see?

There was no leaving the dock without jumping into the water, which was full of beer cans, used condoms, bread wrappers, discarded fishing line, wads of toilet paper. My brother and I watched the boy drag his knife across the lizard’s belly, spilling its innards while it writhed in agony. Later, we went inside and didn’t talk about what we saw.

I think of Florida like I think of my brother. I’ve seen them both at their ugliest and still love them, despite it all.

MOSQUITO COUNTY

I refuse to kill the spiders in my house. I’ve got big ones, large as my hand and fuzzy like rats. When people ask why I let them live, I say it’s because they kill all the other bugs, but really it’s because they’re the only ones with enough sense to avoid people. I appreciate that.

THE SEAM

In Orlando, sinkholes dot the earth, cavities caused by water erosion and the mistreatment of the bedrock. These depressions ingest parks, churches, movie theaters, cars. Once, a local man was swallowed as he lay sleeping. A chasm opened below the house like a yawning mouth, sucking down his bedroom set, his mattress, his life. Rescue workers couldn’t recover the body. They were afraid the mouth might open wider, take in chunks of road, more houses, other sleeping men.

The ground under central Florida is supersaturated and unstable, moldy as an old kitchen sponge. Still we drive our cars along its pitted roads and build homes that collapse in on themselves like dying stars. An Orlando elementary school was the site of a 50-foot wide sinkhole. Construction workers dumped gravel in the wound and built an auditorium on top of it. Students received t-shirts that proclaimed “I Survived the School Sinkhole.” No one worried it would open again and eat the children, though Florida sinkholes recur with cyclical regularity.

Sinkholes become lakes become drained fields become housing developments become sinkholes become reservoirs become playgrounds become a four-story corporate complex complete with parking garage. Driving by rebuilt businesses and model homes, we turn our faces from the wreckage. It’s easier to forget the bodies buried beneath the bedrock. We don’t want to remember.

My grandma tells me that she’s lived in Florida her whole life and can’t recall the restaurant that used to sit two blocks over from her home. I went there once with my grandfather and begged for apple pie. When he bought it for me, I looked at the thick chunks of pale fruit and remembered reading a story about a pastry made out of baby flesh. He was embarrassed I couldn’t finish, but he still walked me home and held my hand.

What is Florida history? Often it feels like the surgical removal of memory. Cutting, slicing out the parts that make us feel bad. We pave over the old and put on the new. We are a city of constant reconstruction. We are a city filled with rotted holes. We are a place looking for stability and finding quicksand.

I am digging out the problem with Florida. The Florida problem. My problem is with the way you talk about Florida, but it’s also in my reaction. Every time you say something bad about this place, you’re talking about me. My heart. My body.

If Florida is a joke, then aren’t I the punchline?

TOURIST SEASON

There are certain types of essays I don’t like and they all have to do with Florida. They’re written by people traveling through the state or by Floridians who now consider themselves former. Both of them are trying to get to the root of whatever mystical, strange force is at work in the state. I’m ready to hate whatever the author is going to say before I get to the end of the first paragraph.

At a bar in another city, I pound my way through five beers as I listen to a woman I’d just met call my home an ugly, unnecessary pit. At the end of her diatribe, she brings up a recent tragedy I refuse to talk about. Eyes watering, she reaches across the table to touch my arm. My queerness and the fact I’m from Orlando makes people think they can touch me now. They do it because it makes them feel better. She leans close and whispers: “This tragedy hits too close to home, doesn’t it?”

I respond to this the way I respond to everything people have to say about it: I keep my mouth shut and finish my beer.

Our grief is not yours to rubberneck at, I think. Pain is reserved for the people who have to live with it.

There’s a gif people like to use whenever they find a particularly vicious Florida headline: Bugs Bunny uses a saw to cut off the peninsula from the rest of the United States. Florida floats away into the Atlantic, adrift and lonesome. It’s easy for people to distance themselves from Floridians, to wish us gone for good. But those same people want to touch our arms, want to see our grief, are ready to share our misery.

This state is a place that engenders feelings of superiority in those who write about it. Travel writers get to drive through and leave. Former-Floridians write about us like they can’t let go, though of course they already have. Maybe that’s where my discomfort comes from. How were they able to disengage? What parts did they have to leave behind in order to get away?

Everything in Florida is a murderer. Everything comes with a warning label. That means the people probably do, too. I think that every time I meet a woman. I think that every time I leave one.

There’s something indigestible about us. You can’t write about the things that won’t let you live.

HOW MANY GAY CLUBS ARE IN ORLANDO?

Not enough. One less now.

ONE MORE FOR THE ROAD

My mother nearly killed the engine in our car once because she put the cheapest kind of gas in the tank and it refused to run on anything less than premium. We sat stalled by the side of the road, a mile away from a demolished sewage treatment facility. It was summer, hot enough that sweat beaded down my neck, staining my shirt. I rolled down the window so I could hear anything besides her yelling. The smell outside was thick, oppressive with sulfur and fumes from other cars. A damp smell like cut grass and mucked leaves.

As I sat, I wondered what it would be like to move away and live in a state where there were seasons and mountains and no palm trees. I looked at my mother, head bent over the steering wheel, crying while my baby sister howled along from her car seat. My mother had lived in Florida her whole life. Her mother was born in Florida, too.

She pounded her fist against the dashboard. Helpless to change anything about herself, her situation, how her home defined our family.

That will never be me, I thought at the time, but of course it is. Of course it is.

THE CITY BEAUTIFUL

I feel most at home when I’m stepping off the plane at OIA. Whenever I leave, it feels like I’m ripping off a limb. There are things we know about ourselves and things we think we know.

What I know about Florida is even when I’m at my worst it wants me, and that’s something like love, isn’t it? That’s the kind of ache I can trust. Orlando is a place that makes me think that anything is possible. Building life out of the rot. Salvaging something out of scraps. This is a place that holds up the dead thing and Frankensteins it to life. I am here for you, I whisper into the black, muggy night. Ugly and terrible and wanting. I’m still here.