The Private Cost of Public Heroism: On Rosa Parks’ Life in Detroit

Susan Reyburn Follows the Life of a Civil Rights Icon

Every black passenger aboard a Montgomery bus in 1957 had paid far more than bus fare to be there. For Rosa and Raymond Parks, the fight had been worth it, but staying in Montgomery was not. During the boycott, Raymond—tagged with having a “troublemaker” wife—was unable to find work. He struggled with his wife’s frequent absences, the hateful calls and letters, and drinking. Rosa, in turn, under the strain of her new life, was in constant worry over his well-being, triggering a vicious circle of worsening physical health and distress for both of them. In the meantime, her brother, Sylvester McCauley, and cousin Thomas Williamson urged them to leave the South. The breaking point came that summer.

Receiving plenty of death threats but no job offers, the Parkses left their home of 25 years and moved to Detroit, taking Rosa’s mother with them. Sylvester McCauley, who worked at the Chrysler factory, found them housing, and Williamson, who owned a cement business, financed the move. Their departure surprised and saddened many, but jealous resentment among some Montgomery civil rights activists toward Parks as an NAACP drawing card and popular figure in the black press made their decision to go less difficult. In August, after a thoughtful but somewhat awkward send-off from friends and associates, the Parkses arrived in the Motor City, ready for a new start.

Like her brother, Rosa Parks never again lived in the Deep South, but unlike him, she occasionally returned. Over the next 50 years, she would remain active in the movement, retreat from public life and reappear, and fight for new cases in the same causes she had long supported.

*

Parks had hardly settled into her new surroundings when she accepted the only paying job to come her way, as a hostess at the Holly Tree Inn, a guesthouse for the Hampton Institute, a historically black college founded after the Civil War to educate freedmen. The tremendous drawback, however, was Hampton’s location at the tip of the Virginia Peninsula, nearly 700 miles away from Detroit by bus. The pay was decent and the work tolerable but demanding. Parks oversaw the dining room and the housekeeping staff and assisted residents and guests, often working late at night. She loved interacting with the students, faculty, and visitors but occasionally found the work dull. At one point she wrote her mother, “My social life is practically non-existent.” Parks was unable to find a position there for Raymond and thus began the two years of correspondence between Detroit and Hampton that forms a large portion of her surviving handwritten letters.

A month into the job, she wrote to him:

My darling husband,

Hearing your voice this morning was such a wonderful surprise. It has made the day so pleasant for me. Of course it makes me want to see you more than ever… I think of you so much and wonder how you are getting along. It is not easy for me to live alone and get along without you being near me. Also try to keep Mother cheered up and help her keep from worrying… I wish you could see this place. It is beautiful and we are almost completely surrounded by water. The campus is right on the bay. There should be plenty fishing from the bank and on boats.

Your devoted wife, Rosa.

The burden of the past two years caught up with Parks, and on November 21, 1957, she told Raymond, “I wrote the doctor [in Detroit] for an appointment in Dec. I felt a bit painful today and I thought it best to make plans for a physical checkup. There are no decent medical facilities here. Only the Institute infirmary for students and a Jim Crow hospital called ‘Dixie’ which I want no part of.” She was also keeping up with the happenings in Montgomery, where a newsman for the Pittsburgh Courier was filing a series of articles headlined, “How Has Bus Boycott Affected Montgomery Negroes?”

In assessing the events of the past year, reporter Trezzvant W. Anderson asked, “Was the Montgomery bus boycott a success? Did it do good? Or, did it hurt those who did the most to make it effective?” He observed that for Parks, such questions bring out “the bitter frustration in the heart of this noble woman who made the great sacrifice. But, after her role in igniting the bus boycott, it was she who paid the price!”

Anderson charged that the Montgomery Improvement Association “failed to sustain and nourish the woman who caused it all! But not once did Rosa Parks grumble or complain, and this reporter was in her house while she was packing and adjusting her things to go to Detroit to live—disillusioned and sick at heart.” Parks was upset all right: “I read the two articles in [the] Pittsburgh Courier and felt sick over it,” she wrote Raymond. “I was called by the Chicago Defender to make a statement. Of course, I would not say anything against the MIA.”

After spending the holidays in Detroit, she returned to Hampton in January 1958, writing home, “The exray of my stomach showed an ulcer. I am on a strict milk diet (2 quarts and 1 pint of cream) with cream of wheat or oatmeal cereal for breakfast and dinner—two pieces of toast for lunch. This is taken 8 times a day along with medicine. I feel very well and am able to work. I have to buy the cream which is very expensive.” Her next letter reported an improvement in health, but finances weighed on her mind, as they always had and always would: “I have to stay on the medicine for two months. It is very expensive ($5.50 for a week’s supply). I am resting and sleeping much better now I want to call, but after thinking of our heavy bills and expense[s], I resist doing so.” In addition to her job and tending to her health, Parks maintained her role as the family seamstress, writing, “P.S. I forgot to mention that I have put the new zipper in your jacket and will try to get it to you this week if possible. I still have to finish Brother’s pants.”

In a birthday card to Raymond in February, Parks noted, “My birthday was quite well remembered by those who knew of it. I was not feeling too well. I must stay on the milk and soup diet one extra week longer. I am taking so much medicine. I can realize now how you must have felt in Montgomery. The same reaction you had seems to have taken a hold on me. I am keeping on the job. It is so much responsibility. This will be a month of many meetings and conferences with visitors to be looked after. I hope you are doing well in school and will continue.” Later in the month, she wrote her mother: “I will go to the doctor again today. He is looking after me without charging any fee, because I am the Rosa Parks of the Montgomery bus protest. This is a great help, for the medicine is expensive.” Ulcers would trouble her the rest of her life.

To Rosa Parks, Detroit was “the promised land that wasn’t.”Back in Detroit, Raymond took classes, taught barbering, and worked as a school janitor. In March, after receiving a letter from Raymond, who preferred phone calls, Parks responded: “I was so glad to receive your letter today. I kept reading it over and over. It seems that we should not have to spend our lives so far from each other. Dearest, I wish that I did not have to be away from you a minute. I can’t write just what I feel that I could say to you. I am trying hard to stay here and make good on the job. I am lonely for you even with so many other people around me. I hope you are not working too hard. I am sorry you have to be away from home at night, but I hope you can get along all right, and making enough money to keep out of debt and maybe save a little.”

After two years at Hampton and of separation from loved ones, Parks resigned and returned to Detroit. She would continue working as a seamstress but would not find a salary comparable to Hampton for another six years. To her, Detroit was “the promised land that wasn’t.” While the overt “whites only / colored only” signage was missing and segregation was not legally mandated as in Montgomery, the longtime practice of redlining—the systematic denial of financial and commercial services to those living in certain sections of the city—resulted in similarly all-black and all-white neighborhoods, churches, schools, and businesses.

In 1960, the year Jet magazine referred to Parks as the “bus boycott’s forgotten woman,” Parks, with little income and in poor health, tumbled to one of the lowest points of her life. Friends and admirers rallied to her side, but having lived a responsible, debt-free life, she found it excruciating to have her situation become public knowledge. Her interests soon turned to local issues, and as an active member of St. Matthew’s, a small ame church, she visited prisoners and shut-ins and served meals; in 1965 she would become a deaconess. She also spent time with her nieces and nephews—her brother and his wife, Daisy, had thirteen children, which made for lively family gatherings. Parks continued to monitor the civil rights movement closely, and she campaigned for attorney John Conyers, an African American, during his successful run for Congress in 1964. The following spring, she began working in his Detroit office, where she would remain for more than two decades.

______________________________

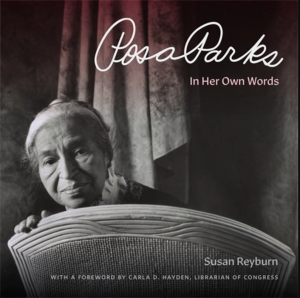

Excerpted from Rosa Parks: In Her Own Words by Susan Reyburn, courtesy of University of Georgia Press in association with the Library of Congress. Rosa Parks’ name and image used with permission from The Rosa and Raymond Parks Institute for Self Development.