Our Father in Heaven

Hallowed be thy name

My father on the farm

Will Collan be his name

The cows come

The cheese be done—

Dear God, I am very sorry about the prayer I said in school, it was heresy and I was rightly beaten. Please forgive me, I know not what I did. Thank you, God.

Amen.

King Edward is lateward dead.

“Deadward,” says Jennott. She says King Edward was a right goodly-looking man who never turned down a tumble, even with low women. She looks sad then, as if at a lost opportunity.

King Edward’s little son, also called Edward, is going to be king. He’s only twelve, a few years older than John. His uncle Richard is Lord Protector for now.

John tries to imagine being a boy-king. His first act: the beheading of Gaspard, for divers villainous buttings-over—and no sign of repentance. Those uncanny slotted eyes say: God is not my master. Yes: Gaspard’s death would be a warning to all goats, and all the little children of England would cheer King John, safe from treadings-on and trampling evermo.

*

Like King Edward, John’s mother is dead. The only thing he remembers of her is the rosemary she used to scent her hair—or maybe he only remembers it because that’s what Tom and Oliver remember. His brothers say she had a mole on her cheek and dark eyes and a creaky but tuneful singing voice. They added once that their mum sang like a dove and Jennott like a crow, and Jennott said, If you fight like a bear you can sing however the fuck you want, and threw a pan at them.

(John crushes rosemary in his fingers sometimes, holds it up to his nose.)

Tom and Oliver aren’t dead. But they are gone, in a way that’s almost as permanent. Tom is an apprentice to a tailor of fine clothing in Bristol. Oliver is learning to be a goldsmith in London. The latter is a passing expensive apprenticeship, and the cause of many meaningful glances in the village.

Will Collan is known to be doing well. Tom and Oliver told John that he hadn’t always done so well. They said that when they were John’s age the farmhouse was half the size it is now, with only one room for sleeping; that there were oilcloth coverings over the window instead of wooden shutters; no pewter ewer and bowls on the table. Their beds were hay, they said, not wool.

John wasn’t sure if they were lying or not. They liked to jape him.

He said, How did our father have so many fields and cows if he was so poor?

Tom laughed and tapped a knockaknock on the top of John’s head.

Think! Tom said. He didn’t have all that back then. He got the fields next to ours when old Allerwych died with no sons. And he bought the cows.

This herd of cows is a curiosity in the village. Nobody has so many as Will Collan—nobody in the county ever thought of having so many, it’s not at all how farming is done, but now they think he was pretty sharp, because he sells his cheese in Oxford.

(Maybe—lowered voice, here—unnaturally sharp.)

So where did he get the money to buy the fields and cows? said John.

Oh, yes: he thought he’d got Tom then. His crow of triumph was already vibrating in his throat.

Tom shrugged. Investment from a rich merchant, he said.

Who?

Some Oxford man. Probably the one who wanted the cheese. John opened his mouth. The caw collapsed out of it, soundless. Tom and Oliver laughed.

Don’t be wroth, Little John, Oliver said. Anyone would think you weren’t the lucky one. The one who gets beef for lunch.

The third son, said Tom.

The one who goes off to seek his fortune, said Oliver. Ey, cheer up, Little John, maybe you’ll fuck a princess.

Little Johnny’s so pretty he could be the princess, said Tom.

John ran across the room with his fists up, shouting, but they were waiting for him, and they wrapped him up in his fancy wool blankets and sat on him. Through the hot layers of cloth, he heard them telling him that this was for his own good, that he had to be wrapped because he’d bitten them before, hadn’t he (sad voice), but once he lay still he’d be released.

Most days ended with John being sat on. He’d always tell himself he wouldn’t attack his brothers again, but they’d jape him until he’d lose his wits and throw himself at them. He wasn’t properly in occupancy of himself at these times. His calmer John-mind, once lost, would fly up and perch somewhere, like the painted angels in the church, watching sorrowfully as his apish body gibbered, howled, bared its monkey teeth—until his brothers bundled the unholy creature up and squashed it.

His brothers are also the ones who taught him to read and write. They showed him how to make ink and sharpen a goose-feather quill and how to write j o h n c o l l a n and then a sigil, which they told him meant John but which even he could see was a drawing of a penis and two balls. They were proud of him for realizing.

He’s a clever boy, said Tom, patting his head. Now, verbs and nouns.

He liked the twins at those times.

*

And all of which is meant to say why, the day that Tom and Oliver left, almost half a year ago, John jumped and hooted and ran laps of their shared bedroom in celebration—then found, on his bed, a whittled boat with a little man inside, with “John” carved into the boat, and had what his father called a womanish fit of tears—

—which took him again whenever their letters home arrived. But not in front of his father. He’d leave the fireside, mannish chin jutting, mannish eyes dry. He’d make a tent of his wool blankets and sit under it and weep in secret.

The knowledge that the blankets would never oppress him again was no comfort.

*

Jennott, despite being a woman, is not given to womanish fits of crying. Especially not concerning the departure of John’s brothers.

She has blond hair, as thick and unshining as hay, and blue eyes, which she puts down to a Saxon lineage. The twins used to do impressions of her behind her back:

Oh, this? It’s just my Saxon lineage, don’t mind it. An unbroken line from Alfred the Great, not that I like to mention it.

John, hearing but not understanding, asked Jennott why shewas a dairymaid if she came from Alfred the Great. A ringing ear, that’s why, said Jennott.

What? . . . Ow.

*

Aside from the whittled ship, John’s favorite thing is a fairy arrowhead. He found it last year, in the plowed furrows of the wheat field. A flint bitten into the shape of a leaf, glossy brown in the center, clear honey glass at the edges. He held it, ran his fingers over the scalloped face.

In the Widow Tolley’s alehouse, the men say John’s father got his gold from the fairies. That Will Collan went over the hills to the fairy barrow on Midsummer Night, set down a pot of ale, and called out, What a right savorly ale this is!

And a door in the barrow opened up, and in the door was standing a fairy princeling. Diamonds on the buckles of his shoes. A cloak embroidered with the moon and stars. He looked at Will and curled his lip.

Give me your ale, Englishman, he said.

(John, hearing this from his friend Rolfe, was suspicious of this story.

Why would a fairy want ale? he asked.

Use your head, said Rolfe. How are they going to make ale, living below-turf? They drink from underground rivers and eat raw mole, envying us our ale and pottage.

Anyway.)

Hold, now, there’s a price for my ale, said Will. I want your fairy gold. And the fairy smiled, and said: Follow me into my palace, and you’ll have all the gold you can carry.

But Will knew that if he went into that barrow he’d never be coming back out again. So he said to the fairy: I think not. And the fairy said, Well then, I will conjure you some from the treasure house, here! And there it was. A whole glistening heap of it. But Will laughed and made the sign of the cross over the gold, and it turned into a pile of dead leaves and acorn shells.

Oh, he knew that princeling’s games.

He knew well. And then he seized that wretched fairy and turned him upsodown and shook him until gold tumbled out of his purse, and rubies, too, sapphires, emeralds—and before he let the princeling go, he took his diamond-buckle shoes. Thank you very much.

Ha!

But as soon as he got home, he put iron at every threshold and up the chimney, too, and he wore a piece of iron as protection, because he full knew the fairy prince was after his blood now, and evermo.

*

Did you steal a fairy’s diamond-buckle shoes? John asked his dad.

God’s bones, said his dad. They’re still telling that story?

Rolfe’s dad told it.

Rolfe’s dad is a cunt.

You did get your gold from the fairies, though, John asked.

Didn’t you?

He wanted this to be true. An upside-down fairy prince, not a cheese-buying Oxonian merchant.

My arse I did, said his dad. And—listen to me—forget about gold. Don’t be noising anything about gold around the village. You hear me? Good.

*

After John picked up the arrow, a feeling came over him. He looked around, as if whoever shot it might be following after, looking for his father—or maybe his father’s son.

He couldn’t see any living thing out here on the fields. Afternoon had collapsed into dusk; a warmish September night. The line of hedge and the trees beyond it were silent. The heaved-up earth was dark under his feet. Smoke rose helically into the purple sky from the low farmhouse in the distance. John had a feeling that eyes were on him: a cool pressure, not friendly, not unfriendly, a gaze from—what? How could he name it, he hadn’t got the words. But he became conscious of not wearing any protective iron.

He put the arrow into his jerkin, not knowing if it was good luck or bad; started back toward the house.

__________________________________

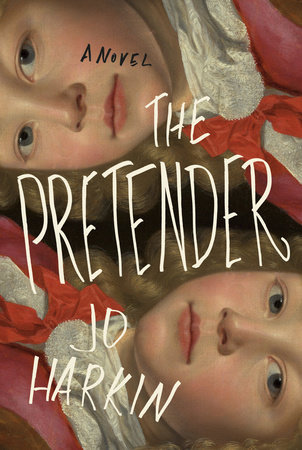

From The Pretender by Jo Harkin. Reprinted by permission of Alfred A. Knopf, an imprint of the Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House LLC. Copyright © 2025 by Jo Harkin.