The Power of Spaces Built for People with Disabilities

Judith Heumann on Camp Oakhurst

I still remember the day I was five and my mother had taken me to register for kindergarten. She helped me put on a nice dress, pushed me to the school, and pulled my wheelchair up the steps. But the principal refused to allow me to enter.

“Judy is a fire hazard,” he said, explaining to my shocked mother how the school system saw wheelchairs as a dangerous obstruction. Children who used wheelchairs were not permitted to attend school. It was 1952.

Over the years since we’d been turned down by the public school and the local yeshiva, my mother had been searching for alternatives and organizing with other parents. We didn’t have a lot of money, so any potential solution for me had to be either a public option or something that fit our family’s slim budget. My mother had sought out parents of other kids who had had polio, researched schools, met with people from the New York City Board of Education, talked to whoever would talk to her, and ferreted out information.

Because of this I’d been placed on a waiting list for Health Conservation 21, a program for kids with disabilities that was offered in various schools around the district. Eventually I’d reached the top of the waiting list, had been asked to come for an assessment, and then finally had been invited to a class. Being put on a waiting list and evaluated for my ability to attend a public school in the United States should have been illegal, but that was overlooked by the Board of Education. And, since the screening hadn’t initiated until late fall it was winter by the time I got approved, which meant that I was starting school halfway through the fourth grade. I was nine years old.

No one I knew would be going to Health Conservation 21, since the program was only for disabled kids, although I didn’t really know what this meant. While I had casually met some disabled kids in the hospital, I had never spent long periods of time with them.

The kids in my class ranged in age from nine to twenty-one. All of us were forced to rest after lunch, including the older students. Given that we got pulled from class for physical therapy, occupational therapy and/or speech therapy, our instructional time added up to less than three hours a day. Which is partly why some students, even at ages eighteen and nineteen, didn’t know how to read very well.

I had started school right at a time when things were starting to change. Parents’ expectations for their children with disabilities were challenging the status quo. Some of the students in the program had parents who were more like mine, parents who expected that their children would complete school, go to college, and get a job. My mother and father rightly worried that Health Conservation 21 was teaching me almost nothing. But they decided that it was better for me to attend than not go to school at all.

We spent hours trying to figure out why we were treated so differently from the “kids upstairs.”

Even though we were glad to be in school, at the same time my peers and I were becoming conscious of feeling dismissed, categorized as unteachable, and extraneous to society. For the first time we were able to describe feelings we’d secretly had for a long time but had been unable to put into words. I confided how uncomfortable I felt when people stared at me, and my frustration about having to wear what my mother had picked out instead of what I wanted because I couldn’t get to my closet.

It was a huge discovery when I found that my new friends felt the same way I did. We spent hours trying to figure out why we were treated so differently from the “kids upstairs,” which is what we called the nondisabled kids who went to school above us. They were the regular kids who went to school at P.S. 219. We were the special-education kids, who were in Health Conservation 21, in the basement. We were kept completely separate.

Unintentionally, the time we spent together at Health Conservation 21—our bonding in the face of exclusion—was teaching us something that would become essential to our success later. We were learning that despite what society might be telling us, we all had something to contribute. We shared similar goals, had similar struggles, and as we continued to grow in the future, we would come to support each other in pursuit of what we wanted our lives to become.

Now I know that what we were all beginning to learn was what today might be called disability culture. Although “disability culture” is really just a term for a culture that has learned to value the humanity in all people, without dismissing anyone for looking, thinking, believing, or acting differently. We were segregated and excluded, and only our parents expected anything of us, but we had found each other.

The summer after I started Health Conservation 21, I went to a summer camp for kids with disabilities. My mother had heard about Camp Oakhurst from one of the other mothers, and my parents had decided to send me.

In one of my earliest camp memories, I am Peter Pan in the camp play. Sarah is Wendy. Sarah has cerebral palsy, and her struggle to articulate her words stretches her lines out into long, heartfelt sentences. But no one cares how long it takes because Sarah has transformed into the perfect Wendy, and June is an impish pixie Tinkerbell in leg braces and crutches. In my role as Peter Pan, I sing so loudly and beautifully that the entire camp is quiet, listening to me. My song is about childhood and my love of independence and freedom. I feel Peter Pan’s love of independence deep in my soul, and this is a new feeling.

At camp we tasted freedom for the first time in our lives. We had freedom from our parents dressing us, choosing our clothes for us, choosing our food for us, driving us to our friends’ houses. This is something we would have naturally grown out of, like our nondisabled friends, but we live in an inaccessible world, so we have not. We loved our parents, but we relished our freedom from them.

I met my first boyfriend at camp. His name was Esteban and he was from Puerto Rico. He had muscular dystrophy and rode in a wheelchair just like mine, which he was unable to push by himself. We both had to be pushed by others. He had a shock of brown curly hair and we liked to talk together. On movie night he took my hand from my lap and held it and we sat, holding hands, watching the films.

The freedom we felt at camp was not just from our parents and our need for their daily assistance in order to live our lives.

We were drunk on the freedom of not feeling like a burden, a feeling that was a constant companion in our lives outside of camp.

Take the summer my mother signed me up for Bible school. This might sound strange for a Jewish child, but she did it because it was an educational activity that would connect me with other kids, the kind of thing she was constantly on the lookout for before I started school. At this Bible school, we sang and played games and did all the things you might expect at a summer Bible school program. But there was a part of the day, a very small part, when some kind of activity happened in the basement, which of course I couldn’t get to. My parents and I were used to accepting these types of barriers, so my mother didn’t say anything about it. We would have accepted that for this small portion of the day I would not be a part of things. But the pastor, who was very kind, offered to carry me down the stairs. A fairly easy thing for him to do, given how small and light I was at the time. My mother, however, stopped him. She told him it wasn’t necessary, that I’d be okay not being with the other kids in the basement.

Now why would my mother, a woman who spent half her life working to overcome barriers for me, have declined an offer to have me included in an activity?

Because she worried I would be a burden.

My mother worried that if having me in the program became too difficult, the pastor might decide the effort wasn’t worth it and wouldn’t want me back. My mother straddled a fine line between fighting to not have me excluded and worrying that she’d pushed so hard for inclusion that I’d end up excluded. At Bible school we were lucky. The pastor was the kind of guy who understood that if all the kids were doing something it would be weird for me not to do it, too, so he carried me up and down the stairs.

But the bottom line is this: My mother worried when my needs became a burden. So I thought of myself and my needs as a burden too. I just kind of accepted it.

Camp was for us. It was designed specifically with our needs in mind and our parents paid for us to be a part of it.

Even though my mother definitely pushed on things, there were certain areas she didn’t push. You did not want your kid to become a burden. Which meant the parents needed us kids to adjust and accept not participating—and we learned to do this. We accepted that our inclusion was dependent on someone else being “nice.”

Getting into Health Conservation 21 felt the same way. It was not like regular school, where you were required to go to school and automatically accepted; you had to be screened. You were given all these assessments and then people actually voted on whether or not they would accept you into the program. Although I don’t think anybody was ever not accepted, there was always the sense that they didn’t have to take you and if they wanted to get rid of you, they could.

But camp was completely different. Camp was for us. It was designed specifically with our needs in mind and our parents paid for us to be a part of it. Our participation wasn’t contingent on someone else’s generosity; it was a given. I didn’t have to worry that if I wanted to do something or go someplace, I’d have to ask somebody for a favor. I didn’t have to feel guilty about how much work it took to get me dressed and take me to the bathroom. The counselors were paid to do these things for us, which made all the difference in the world. Because the reality is, asking people to do something for you when you’re not paying them or they’re not required to do it in some way means that you are asking someone for a favor. And doing favors for someone gets old. Favors mean that someone has to stop what they’re doing, whatever it is, in order to help you with what you’re doing, which always feels like an interruption, an intrusion.

At camp I didn’t have to worry about how much help I could ask for at one time. I didn’t have to secretly rank what I needed in order of importance so as not to ask for too much at once. I didn’t have to feel that bad feeling I got when something was inaccessible or someone said no to something I knew I could have done myself if my whole world had been accessible.

Camp, I thought, was what it would feel like if society included us. Camp was the one other time in our lives when we’d lived in a world that worked for us and our needs. Where we didn’t have to feel inferior for being slow or different. For being a burden. Where we could be ourselves without apology.

__________________________________

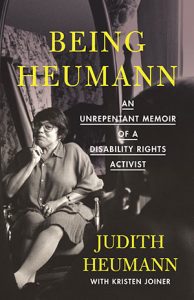

Excerpted from Being Heumann: An Unrepentant Memoir of a Disability Rights Activist by Judith Heumann with Kristen Joiner; Copyright 2020. Excerpted with permission by Beacon Press. Judith Heumann is featured in the Netflix documentary Crip Camp: A Disability Revolution.

Judith Heumann and Kristen Joiner

Judith Heumann, author of Being Heumann, is an internationally recognized leader in the Disability Rights Independent Living Movement. Her work with a wide range of activist organizations (including the Berkeley Center for Independent Living and the American Association of People with Disabilities), NGOs, and governments since the 1970s has contributed greatly to the development of human rights legislation and policy benefiting disabled people. She has advocated for disability rights at home and abroad, serving in the Clinton and Obama administrations and as the World Bank’s first adviser on disability and development. Connect with her on Twitter (@judithheumann) and Facebook (TheHeumannPerspective).

Kristen Joiner is an award-winning entrepreneur in the global nonprofit and social change sector. Her writing on empowerment, inclusion and human rights has been published in numerous outlets including the Stanford Social Innovation Review. Connect with her on Twitter (@kristenjoiner).