The Power of Persuasion: Why Lawyers Love Jane Austen

Natalie Jenner Explores the Legal and Judicial Side of One of English Literature’s Most Beloved Writers

Lawyers love Jane Austen, disproportionately—often rabidly—so. A leading London jurist once memorably quipped of his devotion: “I read all six of Austen’s books every year, because if I didn’t, I would simply read Emma over and over.”

It was a lawyer who ended up saving the central pilgrimage site for Janeites all over the world. The Jane Austen Society had been founded in 1940 with the goal of acquiring the former steward’s cottage in Chawton, Hampshire, where Austen worked on all six of her novels. When the society failed during wartime to raise enough funds, solicitor Thomas Edward Carpenter stepped in to buy the cottage as a memorial to his son killed in action. Carpenter endowed the cottage to the nation, set up a trust (a very lawyerly thing to do) to run the property as a museum, and the doors opened to the public in 1949. Here fans today can see the small octagonal table where Austen sat with ink and quill, spilling out stories now centuries old and never more popular.

More than a century earlier in America, Austen’s reputation among lawyers reached all the way to the highest court in the land. Apparently when the United States Supreme Court wasn’t adjudicating issues of law critical to the young country, its justices were reading—and raving about—Jane Austen.

There doesn’t need to be many lawyers in Austen’s books, because she is already there in their stead.

We know this for two reasons. The first is an 1826 letter from Chief Justice John Marshall himself, rebuking Associate Justice Joseph Story on a very non-legal matter:

“I was a little mortified to find that you had not admitted the name of Miss Austen into your list of favorites….Her flights are not lofty, she does not soar on eagle’s wings, but she is pleasing, interesting, equable…”

The second item in evidence of the USSC’s infatuation with Austen is an 1852 letter of introduction from a Boston woman, on behalf of her family, to Jane Austen’s admiral brother. Eliza Quincy, daughter of a president of Harvard, opened her letter with words designed to impress—and persuade—Sir Francis Austen into sharing more about his sister:

“[The] influence of her genius is extensively recognised in the American Republic, even by the highest judicial authorities. The late Mr. Chief Justice Marshall, of the supreme Court of the United States, and his associate Mr. Justice Story, highly estimated and admired Miss Austen, and to them we owe our introduction to her society.”

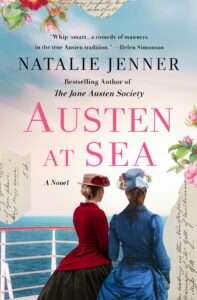

The Quincy family’s letter of admiration to Sir Francis set off a chain sequence of events that culminated (as far as we know) in an 1856 transatlantic visit between the unlikely pen pals. This was the creative spark that inspired my forthcoming novel Austen at Sea. But in fictionalizing the Quincy sisters as Henrietta and Charlotte Stevenson, unable to attend college, bored and bothering famous authors and their relations, I would also transform their father from Harvard president to justice of the Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court. As a former lawyer myself, I am fascinated as to why so many in the legal profession are drawn to Austen’s works. Having owned and written about a bookshop, having studied and written about film, Austen at Sea would be my law novel, I told myself.

When I sat down to write the first chapter (as a former lawyer, I am both on-my-feet “pantser” and creature of habit, the book growing line by line in an orderly fashion), it wasn’t the two Boston sisters who popped onto the page but a group of judicial men in the spring of 1865 engaged in vigorous debate, waving about leatherbound volumes from their laps. I knew right away (while hoping the future reader would not) that the case at hand did not revolve around one of the many weighty issues of that day. Instead, after the jubilant majority and disgruntled dissent leave their private chambers, a servant returns the books to their rightful place on the law library shelves: Northanger Abbey. Sense and Sensibility. Pride and Prejudice. Mansfield Park. Emma. Persuasion.

There were few, if any, lawyers in the Austen family. They were teachers and clergymen, soldiers and sailors. Readers of Austen know too well how much men of trade, law and medicine were socially looked down on by the British elite even as the nineteenth century was ushered in. This is one reason why there are few lawyer characters in Austen’s books, set primarily as they are in village gentry life. It may also be a major reason why Austen’s most significant affair of the heart—with the then-penniless Irish lawyer Thomas Lefroy, future Lord Chief Justice of Ireland—ruptured. But there doesn’t need to be many lawyers in Austen’s books, because she is already there in their stead.

Her stories are rife with rhetoric, that famous literary and legal device that uses tools such as irony and repetition to persuade. My favorite scene in all of Austen is Elizabeth Bennet’s takedown in Pride and Prejudice of the formidable Lady Catherine de Bourgh. Having heard a rumor that her nephew Fitzwilliam Darcy and Elizabeth are engaged, Lady Catherine descends upon the Bennet family home to extract a promise that Elizabeth is not—and will never consent to be—affianced to Mr. Darcy.

“Miss Bennet I am shocked and astonished. I expected to find a more reasonable young woman. But do not deceive yourself into a belief that I will ever recede. I shall not go away till you have given me the assurance I require.”

“And I certainly NEVER shall give it. I am not to be intimidated into anything so wholly unreasonable. Your ladyship wants Mr. Darcy to marry your daughter; but would my giving you the wished-for promise make their marriage at all more probable? Supposing him to be attached to me, would my refusing to accept his hand make him wish to bestow it on his cousin? Allow me to say, Lady Catherine, that the arguments with which you have supported this extraordinary application have been as frivolous as the application was ill-judged. You have widely mistaken my character, if you think I can be worked on by such persuasions as these.”

With the parry and thrust of a courtroom adversary, Elizabeth dismisses Lady Catherine de Bourgh’s every insult with so much rhetorical wit and repetition that she reduces the snobbish aristocrat to—as far as Elizabeth is concerned—the least threatening threat of all: “I take no leave of you, Miss Bennet…You deserve no such attention.”

This power to persuade, when it does succeed, often forms the central cog to Jane Austen’s plots.

Similarly, Mr. Bennet’s famous reply, when Elizabeth refuses to marry the toadish Reverend Mr. Collins, has all the gleeful reverberatory smack of a courtroom litigator leaving the witness box stunned into silence.

“Your mother insists upon your accepting [him]. Is it not so, Mrs. Bennet?”

“Yes, or I will never see her again.”

“An unhappy alternative is before you, Elizabeth. From this day you must be a stranger to one of your parents. Your mother will never see you again if you do NOT marry Mr. Collins, and I will never see you again if you DO.”

Austen is filled with characters who use (or abuse) speech with the dexterity of a seasoned lawyer. She puts words into her characters’ mouths, and they in turn become frighteningly adept. Henry Crawford almost convinces in his love for Fanny Price through the power of his words—Willoughby almost moves the sister of Marianne, who lies near death from a malady brought on by his cruel rejection, with an eleventh-hour speech. A speech so self-justifying—yet so unconvincing and therefore foul—that screenwriter Emma Thompson wisely omitted it altogether from the movie adaptation for which she later won the Academy Award. In the end, for all their words, what keeps these “bad boys’” from winning is the moral failure of their deeds: a triumph of reality over perception if ever there was.

This power to persuade, when it does succeed, often forms the central cog to Jane Austen’s plots. Persuasion wouldn’t exist if family friend Lady Russell had not talked Anne Eliot out of marrying her one true love. Similarly, there is a hilarious sequence near the start of Sense and Sensibility, captured so well in the Ang Lee film version and Emma Thompson’s script, that leads to the homelessness of its sister heroines.

Fanny Dashwood, through verbal manipulation of the highest kind (what world would we now live in, one shudders to ask, if Fanny could have ruled more than the roost?), easily convinces her dithering husband that—in contrast to the deathbed wishes of his father—it would actually be better for his disenfranchised mother and sisters not to receive a meaningful bequest. The scene goes on at length, Fanny taking and twisting every one of her husband’s arguments into so many knots he is left tongue-tied, all opposition mute, all acquiescence complete. I think of this scene a lot right now, the ascension of repetitive and escalating noise into meaning. I fear Jane Austen would be rolling over in her grave.

__________________________________

Austen at Sea by Natalie Jenner is available from St. Martin’s Press, an imprint of Macmillan, Inc.

Natalie Jenner

Natalie Jenner is the author of the instant international bestseller The Jane Austen Society and Bloomsbury Girls. A Goodreads Choice Award runner-up for historical fiction and finalist for best debut novel, The Jane Austen Society was a USA Today and #1 national bestseller, and has been sold for translation in twenty countries. Born in England and raised in Canada, Natalie has been a corporate lawyer, career coach and, most recently, an independent bookstore owner in Oakville, Ontario, where she lives with her family and two rescue dogs.