The Power of Absence: How Loss Can Help Fuel a Creative Life

Sanam Mahloudji: “If I didn’t feel an absence or a sense of loss, there would be no need to write.”

When I was nine years old my mother temporarily moved from our home in Los Angeles to New York City for a job in private banking. The family lore is that I wrote her letters, including short stories about a family of hamsters. I don’t remember what I was feeling then or why I did it, or even writing these stories. Decades later, I wonder if they help explain the urge I still have to make up tales.

Did my mother’s absence create in me a longing that I coped with by writing about a furry substitute family? Did I send her the stories to entice a return?

I believe that absence is elemental to my writing. If I didn’t feel an absence or a sense of loss, there would be no need to write.

In trying to find a unifying theory as to when absence is helpful, I wonder if it is when absence is conducive to imagining, to making up worlds.

In 2010, my father died and I started writing fiction for the first time as an adult. Why hadn’t I been writing in the intervening years? It was not conceivable to me that making art was something I could do professionally. Life was for doing well in school, choosing a career, becoming a lawyerbankerdoctor. By age thirty, I’d been two out of three of these things—not bad, right? Or maybe really, really bad.

In the year after my father’s death, writing fiction was a way to enter an alternate world, one that I could control. One with no risk of real death. Yes, there was a dead dad in every short story I wrote—but no humans or animals were harmed on the page. The absence of my father created something inside me—I call it the correct weather for fiction. His absence gave me space, distance, and an emptiness I needed in order to create. Maybe this is what happened when my mother left my childhood home.

In Deborah Levy’s book on writing, Things I Don’t Want To Know, she says “I had come from somewhere else. I missed the smell of plants I could not name, the sound of birds I could name, the murmur of language I could not name.” This sentence scratches at something deep within me. I wonder if it is the absence of these things—plants, birds, language—that makes Levy attuned to them? She describes what I feel about Iran, where I was born but left at age one and have never returned. I am homesick for Iran, longing for a place I don’t remember. When widespread civil unrest and protests were underway in Iran after Mahsa Amini’s murder in 2022, I often felt that there was nothing I’d want more than to move back to my country of origin.

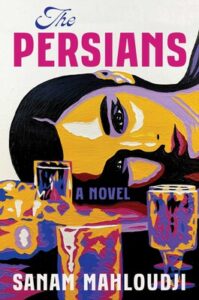

This absence of Iran, even before 2022, created the weather that led me to write my first novel. The Persians is a multi-generational story about an Iranian family, spanning 70 years. Some of the novel is set in Iran. I go into the minds of a grandmother, her two daughters, and their two daughters. I didn’t grow up in the same country as either of my grandmothers. One stayed in Iran, the other lived the rest of her days in France. I went to the United States with my parents. If we had all remained in Iran, I wouldn’t have needed to write this novel. To place make-believe characters inside Iran. To imagine a family, to know them in a way I haven’t known my own in part because of how the Islamic Revolution split us up and placed us on different masses of land.

*

In 2017, our family left the United States after my husband took a job in London. At first, I worried the sacrifice I was making would be too huge—leaving everything and everyone I knew. But this is another absence, or distance, that has given me space for writing fiction. I can get a lot done with a five hour headstart on a day before headlines from the United States take over the news.

The idea is to find space, time, distance from what otherwise occupies us so that we can clear space for creativity.

The more I look for these helpful absences, the more I find. The absence of my Los Angeles community has given me more time alone for writing. The absence of the familiar means that I notice more in London. And writing is dependent on the act of noticing. The absence of the United States has meant seeing the United States with fresh perspective, removing it from its central spot. It has meant feeling the freedom to write characters who never lived in the United States.

The musician Nick Cave has said that when a loved one dies “their sudden absence can become a feverish comment on that which remains….a luminous super-presence—as we acquaint ourselves with [a] new and different world.” Maybe absences work like this—leaving me “a luminous super-presence.”

But not all absence operates this way. Experiencing loss, absence, and emptiness doesn’t come without risks. When my father died, for example, I was not free of pain or worry or problems. But I realized that I could exist in two ways at the same time. There was the grief me, and there was another me—the one who could sit at a desk and make up a story. In trying to find a unifying theory as to when absence is helpful, I wonder if it is when absence is conducive to imagining, to making up worlds. Perhaps the absences that help a creative life are ones that you can separate yourself from—ones you can stand outside of, reflect upon. When the absence takes a shape that leads you to discovery. The idea is to find space, time, distance from what otherwise occupies us so that we can clear space for creativity.

__________________________________

The Persians by Sanam Mahloudji is available from Scribner, an imprint of Simon & Schuster.

Sanam Mahloudji

Sanam Mahloudji was born in Tehran and left during the Islamic Revolution. She is the recipient of the Pushcart Prize and was nominated for a PEN/Robert J. Dau Short Story Prize for Emerging Writers. Her writing has appeared in McSweeney’s, The Idaho Review, The Kenyon Review, and elsewhere. Mahloudji was raised in Los Angeles and now lives in London with her husband and two children. The Persians is her debut novel.