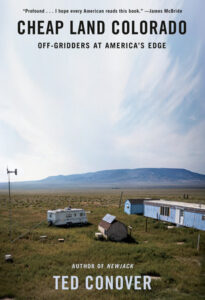

The Politics of Independence: Living Off-Grid in the Colorado Foothills

Ted Conover Gets to Know the Homesteaders of the San Luis Valley

I stayed on the Colorado prairie for the first half of January 2018, and then I was there for some of every month except November. The living was a little rough—just one reason it felt like a perfect complement to my life in New York City. Fewer people meant more space for me. I liked the slower pace, how affordable things were, the strains of Hispanic and Mexican culture (including the food).

I liked the weather, which was never dull; the sky changed all day long, sometimes dramatically so, always grabbing your attention. I liked the varieties of people, many of whom you probably wouldn’t find in a big city. And I appreciated the less-pressurized feel of life among those less set on leaving their mark than my circle in New York. It was a beautiful, wild, and mysterious world, home to the semi-destitute.

Most simply, of course, off-grid meant not connected to public utilities. Many people associate “off-grid” with “green,” and credit off-gridders with trying to live lightly off the earth by reducing their needs, unplugging from utilities and rejecting conspicuous consumption. The model for upscale green living was headquartered just about an hour away, outside Taos: Earthship Biotecture was renowned for the creative ways their houses, known as Earthships, incorporated cast-off materials such as bottles and tires, and for their efforts to conserve and recycle water inside the house.

I took one of the company’s tours and saw some inventive houses it would feel good to live in: they made smart use of the area’s abundant sunlight, and some had gardens inside. Teams of young people were helping with construction, all of them paying for the privilege. Their interest in such things as “tiny houses,” renewable energy, leaving the grid, and reducing humankind’s carbon footprint was inspiring to me, and hopeful: they saw that urgent action was needed if we were to save the planet and wanted to respond to my generation’s failure to act. The company had been a pioneer in green construction and green thinking since the early 1970s. But I also noticed how expensive Earthships were—far too costly for most people I’d met in the valley. The paradigm had another flaw: most of the Earthships seemed to have propane tanks out back, painted tan for camouflage, which seemed like cheating.

Earthships were just one kind of upscale off-grid living. I experienced another on a weekend expedition to the Sangre de Cristos, where a young couple I’d met had built their own off-grid place on land in the mountains, with trees. It was more expensive than living down on the flats but also felt more protected. My hosts invited me along to a weekly potluck meal farther up their unelectrified valley, and there I saw something I hadn’t imagined: a full-sized suburbanstyle ranch house with an expansive lawn and enormous solar panels on racks that swiveled to follow the sun and massive batteries that stored all that energy.

The husband of the couple who owned it was a former military intelligence guy, at home with electronics. He told me that normally his system was adequate to power everything you’d want in a city, including a clothes dryer and air-conditioning. Only if a string of cloudy days left them a bit short, he said, would he power up his generators. He was proud to live independent of the grid and saw no need for all of the “hippie” trappings of the Earthships set.

(In some ways, the green tech of Earthships had had unanticipated ill effects. Their embrace of used car tires, for example, had probably resulted in the collections of them you’d see on some of the prairie lots of Costilla County. Yes, packed with pounded earth they could be used in walls to both insulate and support, but many people never got around to that part of things. Instead, they’d leave a couple dozen, or even a couple hundred, old tires strewn about their land, where they never decomposed and always looked bad.)

The San Luis Valley, with its extra-cheap land, was a sort of mecca for these off-gridders. There were probably more than a thousand people living off-grid here, though nobody seemed to know for sure.

Certainly down the economic ladder a few rungs were the people with environmental consciousness who were drawn to the virtue of not needing much, and who appreciated the creative reuse of discarded materials, communalism, “tiny houses,” and outsider art. Among these was the occasional college grad. Some college-educated people were down on the prairie, but more seemed to be up in the woods.

Prairie people overall just seemed poor and wanting a different life—one with more self-reliance, fewer bills from utility companies, and, in many cases, lots of distance from neighbors. Most seemed to be escaping more typical American lives that had become unsustainable, whether because of too many bills or too many disappointments.

They arrived pulling trailers or with old RVs and set up camp. Sometimes they would build something, but often the trailer became the building block, added on to with shacks or Tuff Sheds. They drove Fords more often than Toyotas. Their political consciousness tended toward the Trumpian: anti-government, pro-gun, America first, self-reliance. Among them were preppers, homeschoolers (Christian and otherwise), sovereign citizens, weed lovers, and Hillary haters. Some had lived near a coast, but more seemed to come from the heartland, many from the South. And most were very poor.

The San Luis Valley, with its extra-cheap land, was a sort of mecca for these off-gridders. There were probably more than a thousand people living off-grid here, though nobody seemed to know for sure. (Nationwide, the number is probably in the tens of thousands, though again no authoritative numbers exist. Off-grid life seems to be growing in the United States, often in regions with cheap land, like Appalachia; or sunshine, like Hawaii, Utah, Arizona, New Mexico, Texas, and Florida; or frontier appeal, like Alaska, Idaho, Wyoming, and Colorado; or environmental consciousness, like northern California, Oregon, Vermont, and even New York.)

A flip side of having all that space to yourself can be loneliness. A friend of mine who grew up in rural Vermont and Maine had spent time in Wyoming and Colorado living alone in a trailer while working on a ranch and as a hunting guide. So when he heard I was alone in a trailer in the wide-open spaces, his first reaction was concern: Are you all right out there? He had not always been all right. He offered to talk to me about it anytime, which I appreciated.

But I was coming to the conclusion that my life out there was, emotionally speaking, usually good and often much better than that. Some of this was my collaboration with La Puente, a group of people I admired and connected with. And some of it was having the Grubers for neighbors. A good bit of this was learning what they were thinking and talking about on the many occasions when the kids stopped by, usually Trin and Meadoux but sometimes Kanyon or all three of them, or occasionally four (including Saphire). They would knock at my trailer door, then enter and stand just inside while I sat at my breakfast table. They would bring me drawings and news of the animals. Stacy told me to tell them to go away if I was busy, and sometimes I did. But mostly I welcomed them.

They told me how Lakota had badly cut her foot (sharp things abounded at the Grubers’ place) but that they had cleaned the gash and applied antibiotic ointment. They told me how one of the Nigerian dwarf goats was certainly pregnant and overdue. (They had a kids’ ultrasound device powered by a radio battery.) They also told me how Meadoux had recently crashed into a pronghorn antelope on her bike. She and Trin were on their way to Jack’s RV, a mile or two away.

Jack had told the girls that if they proved they could look after his two horses for a few months, watering and feeding them, they could have them. Often Stacy drove them over, as she did on my first day there, but on this day, they had decided to ride their bikes.

There were some hills between Jack’s place and theirs, but the girls were strong. The bikes were nothing fancy, and Meadoux’s lacked brakes, but out here that didn’t really matter . . . until it did. Riding into a stiff headwind, they crested a hill and saw a small herd of pronghorn antelope resting just below. The wind was so strong the herd didn’t hear them, and some didn’t see them until it was too late. It was a fairly soft collision, from the sound of it: Meadoux said she “almost hit a baby” but that the pronghorn she did strike bounded away as if nothing happened. Trin said, “I crashed my bike, but I wasn’t hurt because I was wearing my parka and I rolled.”

I told them that one thing I missed from New York was walking everywhere. They said they sometimes walked the goats and I should join them. Some dogs came, too. Trin, the oldest girl, helped me put names on some of the plants I’d come to recognize: those were yuccas, these were chico bushes, that was a sage. And the girls identified things that were mysterious to me, such as the hoofprints feral horses left on dirt roads or holes where a ground-dwelling owl might live. They were experts in the natural world around them.

Their book learning was less advanced. Like some other kids in the area, they were homeschooled—but this could mean different things. Some of the kids whose families had internet service were enrolled in an online curriculum called Branson. They had regular class meetings and homework assignments, and they passed through grades like kids in ordinary schools—the state of Colorado even supplied them with laptops.

The Grubers, though, didn’t have internet, apart from the data on their phones. Stacy told me she relied on a series of textbooks and workbooks that the kids’ old school, in Wyoming, had let them have when the teachers upgraded to a new edition. She made the kids spend time on their studies every day. Though she was smart, however, Stacy wasn’t highly educated—neither she nor Frank had finished high school. And she was a truly terrible speller. So the odds of her kids getting a good education were low.

I knew that Trin and Meadoux were proud to live on the prairie but also that life for their family was hard, with few creature comforts and a constant shortage of money. The girls appreciated trips to Denver to stay with their aunt, or even to nearby Antonito, where they could get a good signal on Trin’s smartphone. (Most places on the prairie had poor cell service.) They watched TV and knew what was happening in pop culture. When I shared a story on Facebook about New York City teens who had their own fashion sense, Trin was the first to like it.

One day the girls mentioned that their cousin, Ashley, was coming to stay for a few days. Stacy initially told me that Ashley just needed some time away from her mom up in Oregon. But then it became clear that Ashley’s needs were a bit more specific, and urgent: she was there to withdraw from opiates, and the Grubers had offered to look after her while she did.

Frank and Stacy drove into town to pick up Ashley at the bus station. But after that, the news was spotty. The girls complained that after initially being given Kanyon’s room, Ashley had taken over the couch in the living room. She seldom moved or pitched in. Around day four, Stacy asked me if I had any Benadryl, because Ashley’s skin was crawling, extremely itchy. Luckily I did. Around day six, Ashley came outside to sit on the front steps in the sun for a while. I stopped over and said hi. Ashley was friendly and said she was feeling better. She’d be going back before too long.

“Back to Oregon?” I asked.

No, she said, probably to California, to stay with her dad. She’d recently learned that there was a warrant out for her arrest in Oregon—she’d crashed her car not long before she came down to Colorado. Ashley was guessing that the cops might have found her drugs. “I’m just happy they didn’t find the gun,” she said.

“You had a gun in the car?” I asked.

“Well, sure. If you’re going to deal, you’ve got to be able to defend yourself.” I had heard that was true.

Others came by, too. Josh had been friends with Stacy since her Casper days, before she met Frank. Then he had married Meg, and the couples had been neighbors in Farmington, New Mexico, where Josh worked as a technician examining pipelines. But Meg had never gotten along with Stacy—she insinuated that Stacy was a drug user. When Frank and Stacy moved to Colorado, Josh and Meg moved to the Northwest, where they had a daughter and Josh found a new job. They bought a house and a new truck and life was good.

But then Josh got fired and it all fell apart. They lost the house, moved into their small “fifth wheel” camper trailer, and took refuge at Frank and Stacy’s, where they parked not far from my trailer. The arrangement didn’t last long. Given her history with Meg, it seemed generous for Stacy to let her stay. But Meg wouldn’t go in their mobile home, and before long she had taken their daughter and moved to her parents’ house in New Mexico. Josh became a long-term guest.

A little later in the spring, the Grubers introduced me to Sam and Cindy, who lived a few miles to the south. It was a gruff sort of meeting; the middle-aged couple were sitting on the Grubers’ couch with their coats on, smoking weed, when I arrived. Sam responded reluctantly when I offered my hand in greeting. I later learned that Sam and Frank had met in an online chat room about living off-grid in the San Luis Valley before the Grubers bought their property here. When somebody else cautioned against bringing a family with small children to live on the prairie, Sam countered, saying, effectively, Don’t listen to these people, it’s great. Message me. Frank had done so and had been persuaded. Once they were situated, Frank told me, Sam had brought them a goat and some marijuana plants.

This new five-acre property had some history. In keeping with much of the settlement in the valley, it was short and violent.

Now Sam and Cindy were considering selling their place to the Grubers. Negotiations were well along. The price, Stacy told me, would be $30,000, with $2,000 down and monthly payments—and, presumably, a lump-sum payment when they sold the mobile home and had some cash. But why would you move when you have a nearly new place? I asked.

Stacy said she’d show me, and so one day we went over in her truck.

I recognized the place from my reconnaissance—I had once honked outside the front gate but gotten no response. It was one of the few properties with a wooden fence along the road, which made it look substantial. Stacy pointed out the other thing she really liked: a modest built house. It was smaller than the space they were in now, she acknowledged, but she thought they’d fit. “And it would be so nice not to have to live in a trailer”—a bit because of the stigma, I think.

There were nice touches, like a small faux railroad water tower that enclosed an aboveground water tank, and an outbuilding where she said the older girls could live. But best of all, she noted, was that it had a well. “So you could almost live like a normal person,” with a washing machine (included) and shower and no need to buy water from neighbors, and constantly rationing your use and refill.

“And there’s room for your trailer,” she said, indicating two possible spots.

“Hmm,” I said. One of the spots had a great view of untrammeled prairie. “When would this be?”

Stacy said within a month or two. Josh, she added, would stay behind, to keep an eye on the mobile home.

And so it transpired that, six months after I first joined them, as spring gave way to summer, I moved with the Grubers to their next place.

Most of the moving happened when I was in New York. My trailer was one of the last things to go. Sam did me the favor of towing it behind his powerful GMC Yukon, a task accomplished in under an hour. But that still left one more big thing: Frank’s little bulldozer.

No trailer was large enough to load up the dozer, so it would need to be driven the nine or so miles. At five miles an hour, this could theoretically take under two hours. But there were problems with the hydraulics. There were problems with the tracks. There were problems with the diesel fuel: when it ran out, it needed to be resupplied from a tank in the abandoned RV where the Grubers had lived before their mobile home arrived.

Frank, Stacy, and Josh got started in midafternoon, but as of 9 pm the bulldozer had come only a fraction of the way. Sam, a skilled mechanic, got involved as well. A bit before midnight I drove out to check on their progress. I looked for the lights of the pickup truck. It was following the bulldozer, its headlights showing the way over the dirt roads. The tracks left by the dozer were zig-zaggy, and days later would still be visible.

“Why not just leave it till morning?” I asked. “Somebody could steal it,” said Frank. And so the dozer crept, and stalled, and crept, and stalled, and finally, I was told, arrived shortly before dawn, its journey reminding me of the mule-drawn wagon carrying the casket in William Faulkner’s As I Lay Dying.

Unlike the Grubers’ old place, this new five-acre property had some history. In keeping with much of the settlement in the valley, it was short and violent.

Lisa Foster had bought the land from an ad on eBay, sight unseen, for $3,027 in 2007. She and her husband, Bob, childhood sweethearts from rural New Mexico, were living in Las Vegas, their children grown. Lisa had worked as a contractor, specializing in home renovations for disabled people. “It was always a dream of mine to build a place from the ground up,” she told me. “I got to live that dream out there.”

Lisa shared with me a slideshow of the summer after she, her husband, and a friend first broke ground, in March 2008. No other settlements were visible in the area at the time, she said. First they put up a tent to stay in. Next, with a touch of humor, came a tall post with a house-shaped birdhouse atop it. Then they built a one-room cabin, an outhouse, and a good-sized shop building, with fences around the whole property. In the photos the three of them, none younger than fifty, look industrious, happy, and, at the end of the day, tired.

Lisa continued to build in the five years she spent there. Bob was often away (he was a manager for Verizon in Las Vegas), so in most ways it was her show. Tired of driving into Antonito for water, she soon spent $19,000 on a well. Enamored of horses, she made friends with a notorious local character known as AJ, who kept a lot of them “and had foals that needed help”—so she built some corrals. She acquired a dog and soon had five. “But the first one was just a pain in the butt,” always barking, biting, and starting fights. “One day I just had it with him, and I shot him!” News of that got around the neighborhood and people started saying, Stay the fuck away from her, which she regarded as a positive. “The only people who found me were Jehovah’s Witnesses.”

For her first three years, she said, “It was just heaven.” But then it wasn’t.

In reality, Lisa had a soft heart, which would be her undoing. One winter day she noticed a family of six apparently living out of their car, basically in the road, not far from her home. “They had four babies out there in twenty-nine degrees below zero, and they were living in this little bitty car, nowhere to stay.” They had set up a playpen next to the car. One of the children was a newborn. Lisa stopped and talked to them and later brought them food. Then “one night they just showed up at the door—it had been raining, and I just let ’em come in. I thought they’d be helpful.”

Instead, they slowly took over. They helped with very little and “never paid any rent.” The husband insisted that he wanted to buy the place, even though she didn’t want to sell. He could get hostile and weird; she later learned that he had been a security guard and had had to flee Dallas one night after he angered members of a local gang. The couple promised to take care of her place and her animals during times she was away, but instead they neglected them, and ultimately, “they killed all my dogs. I was very naïve, I just didn’t see it. I brought them in because of the kids,” but the arrangement was her undoing.

After the wife “got into my phone” and read texts, including one where she admitted to preferring her own grandchildren over the couple’s four kids, things got worse. The husband threatened her with a gun. She moved out, perhaps temporarily—she wasn’t sure. Eventually, with the help of the county sheriff, she evicted them, but not before they had burned or otherwise destroyed much of what she had built, including furniture and corrals. It was, Lisa said, an “ugly ending.”

That ending was redeemed somewhat when Cindy and Sam contacted her out of the blue, saying they hoped to buy the place. “I sold it to them for the cost of the well,” or $20,000—a net loss of about $30,000 on the $50,000 she’d put into it.

Sam and Cindy, both of them army veterans who had come to the valley around 2008, a few years after medical marijuana became legal, had lived only a couple hundred yards away. Sam said that the man who took over Lisa’s place told people he owned it and was threatening and unhinged. “One day this crazy dude came crawling up on us with a roofing hammer! My buddy Geno comes out of the RV with a shotgun and says, Watch out, dude, I’m gonna blast you! He left us alone after that.”

Lisa’s place, even with the damage done to it, represented an upgrade—according to Sam, there were only eight places on this part of the prairie with wells. He and Cindy moved in and for a couple of summers grew a lot of weed. It was physically demanding as well as stressful from a security point of view. Sam described how one year, near harvesttime, members of a motorcycle gang had turned up and said, We’re gonna take thirty pounds and here’s what we’re gonna pay you, or else you’re getting a couple of bullets in the back of your head. His response: Well, hey, fucker, I’m armed, let’s get started right now because you’re not taking my weed. The gang backed off, but Sam lost his taste for the enterprise.

He and Cindy also had health issues. Sam said he had stage 4 cancer, with tumors on his liver, spleen, lungs, and more, which he blamed on the years he had spent as an industrial welder in a packinghouse, breathing in harmful fumes. Cindy, for her part, had non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma as well as breathing issues, likely COPD. They made a deal to sell the place to a guy in the neighborhood, who made a down payment and moved in.

Meanwhile they pursued a lifelong dream of sailing. After driving to Marathon, Florida, they bought a diesel-powered boat and chugged off toward the Gulf Coast of Texas. Unfortunately, Sam said, the guy failed to make his promised payments but remained on the property. Weeks passed, the sailing adventure ended, Sam told the man to get out, but he wouldn’t—it sounded like Lisa Foster’s squatter scenario all over again. Finally, the guy left. Sam, still in Texas and nervous about what shape he’d find the place in, asked Stacy if she’d go over and look around. Stacy discovered that items were missing, including a gasoline generator and a wind turbine, and that there was a lot of new, unwelcome junk on the land, including a large portable toilet.

This kind of story was common on the prairie, I would find, and a reason that renting wasn’t often done and property deals often fell through. Stacy had rallied to Sam and Cindy’s cause, reporting the theft to the sheriff ’s department, posting about it on Facebook, and, she said, trying to calm down Sam, who had worked himself up into a rage she feared might turn murderous.

And in this dramatic fashion began the summer of 2018.

Life with the Grubers was eventful already. But adding Sam and Cindy to the mix, especially Sam, upped the ante considerably. They remained the owners of record, even if they had let the Grubers move into the main house. Next to that house was a semi-enclosed area for the marijuana grow, and next to that was Sam and Cindy’s little trailer. And next to them—a little closer than I might have wished—was my trailer. In front of their trailer on a couple of chains, or sometimes in cages, were their pit bulls, Fatty Wolf and Speckles, who would bark savagely and lunge at me when I walked past, even after they knew me. This was always unnerving, something I never got over.

Another source of noise and peril were Sam’s firearms. He loved shooting, “modding,” and collecting firearms. His Facebook profile picture featured the custom AK-47 he took with him whenever he drove anywhere. I never saw him handle guns recklessly, but just having them nearby, and subject to frequent use, put me a little on edge— particularly since he enjoyed his beer and weed and could get a little lit at night, and because he was often upset about things.

The last member of the cast at the Grubers’ was Nick. He was typical of what Sam would affectionately call a “prairie rat”—young, aimless, willing to work occasionally but largely destitute, a drug user with a couple of screws loose. (Sam sometimes used that phrase to describe flats dwellers generally.) Nick was buddies with Junior, whose RV had occupied the space my trailer had moved into at the Grubers’ old place. Junior had grown up locally and had once lived at a different location with Nick. The story went that they’d had a fight after Nick had failed to water his marijuana seedlings and they’d all died.

Nick had strong eyeglasses and was physically unimposing. Like Sam, he enjoyed discussing guns and the uses to which they might be put. He would say, with some frequency, things like “I’d just take a thirty-aught-six and cap him” or “a derringer would fix that problem,” and then mime shooting the weapon cited.

His most prominent tattoo, on his upper arm, was of a wild-haired running figure, shaded red, brandishing a hatchet dripping red drops; it was the logo of Psychopathic Records, the label of Insane Clown Posse. Nick explained to me that when his family had lived in Aurora, Colorado, and a process server had tried to serve his dad, Nick had gone after the guy with a hatchet. That earned him a felony menacing charge, he said, which he beat in court by producing evidence that he is disabled by fetal alcohol syndrome. “My mom is an alcoholic.”

He had been in schools for troubled kids. But despite his challenges, he was usually mild-mannered and friendly, a follower type. The Grubers let him sleep on their couch for several weeks in exchange for helping around the house. Later he moved into a small room next to the shed (Lisa Foster’s old workshop) and, still later, into a small trailer the Grubers helped him buy.

As the prairie warmed into summer, I continued to work with La Puente for part of the week. But most of my life was on the prairie, and a lot of it revolved around the Grubers. Trin caught cool lizards with blue bellies and showed me. Kanyon explained that the tiny burrs that stuck to my socks were called “goatheads.” Meadoux announced that Lakota had given birth to a brood of the cutest puppies—the family’s dog population was now over twenty. Stacy filled out applications for Trin and Meadoux to spend some of the summer at a free sleepaway camp. Jack’s horses were now in residence and beautiful to watch as they grazed over the five acres; early one morning I saw them move into light reflected off the window of an old truck in order to warm themselves. Occasionally, Trin or Meadoux would climb on their backs and move lazily around the property.

One of the family’s pleasures was to take an outing to “the Beach”—a sandy stretch of the Rio Grande just a couple of miles away. For much of its way through the prairie, the Rio Grande was hard to access—and near the Grubers, it was sunken into a narrow canyon. But the Beach was a lovely exception. Several times I helped transport members of the crew there.

One day in June, Stacy packed a picnic. While the little girls played with pebbles by the water’s edge, Trin and Meadoux waded out and caught crayfish. Stacy encouraged them to catch more—“We can make a stew with them!” Frank, meanwhile, pointed out a camper trailer parked a couple hundred yards away. The occupants were squatting there, he said, which was not good—though the area was not officially a park, the Grubers and others treated it that way. The idea of somebody taking over a piece of it for the summer struck them as wrong.

Stacy said that Sam had nicknamed them “the Shims,” for she-hims. That didn’t sound particularly helpful. I mentioned them to Matt, who said he had first noticed them in line at the spring where he got water. The man was big and wearing purple heels, he remembered: “Unusual for around here.” His partner, on the other hand, seemed to be a female who embraced a very masculine style.

Since then, he’d seen them around, in Fort Garland and in Blanca and once walking between the two towns, which he guessed might have been because they had been pulled over by the police and didn’t want to get busted again before correcting something they’d been cited for. And then he saw them with their trailer, parked in a hard-to-see area near where he lived. A friend of his had driven by and, noticing a distinctive, “metallic acidy smell, almost like battery acid,” believed they were cooking meth. A rumor, which initially struck me as far-fetched, held that they were perhaps saving up for gender transitions in Trinidad, Colorado, a nationally known center for that located about an hour and a half away, over La Veta Pass.

I went by the camper on the Beach a couple of times after that day, to see if they needed anything. But they weren’t at home. On a visit to a neighbor who lived a bit closer to the Beach than the Grubers, I asked if he’d had any contact. He answered that on a walk down there he’d seen them working on the transmission of their truck, which they had taken out and placed on the ground. In short, he’d said: “Trannies working on a tranny. You can’t make this stuff up.”

Somebody else told me they’d confronted the couple after seeing them pump water out of the Rio Grande, which is against the law.

Then late that summer, after I’d been away a few days, I saw that Sam’s big GMC Yukon was dented up and missing its entire hood. Sam said there had been an altercation. He, Frank, Nick, and Josh had driven down to the Beach on a recent evening, around ten. As Sam told it, the larger of the “Shims” drove up to them in his truck and they exchanged words. Shortly afterward, the guy turned off his headlights and surprised them by ramming Sam’s SUV with his pickup. Sam’s airbags deployed. Shots were fired; a dog might have been hit. Sam drove onto a rock he couldn’t see in the dark.

Sam reported that the next day, the guy had driven by and shouted at them from the gate. And that a day or two after that, he said, “lightning must have struck because his trailer burned down.” I went to see for myself. Ashes were the main remnant of the trailer—that and its steel chassis. I hadn’t known that trailers could burn so completely. A short distance away from it I came across a single, very large men’s sneaker . . . and remembered Matt saying that the man had big feet. I took the sneaker with me.

I imagined there was more to this story and tried to learn it. But it appeared that no police reports had been filed, and nothing of it made the news. I kept asking flats people if anyone had seen the couple. Finally came a report that they were squatting at the foot of Blanca Peak, in a different trailer. I went to the place and again found nobody home. I left behind a La Puente card and a note saying that they could call me if they needed assistance. They never called. A few days later, I passed by the site again and they were gone.

Were they criminals cooking meth? It seemed possible. Were they also victims? That, too, seemed possible. Was prairie justice tainted by anti-gay or anti-trans bias? That seemed possible as well.

__________________________________

Excerpted from CHEAP LAND COLORADO by Ted Conover. Copyright © 2022 by Ted Conover. Excerpted by permission of Alfred A. Knopf, a division of Penguin Random House LLC. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.

Ted Conover

Ted Conover is a journalist and associate professor of journalism at New York University. His book Newjack: Guarding Sing Sing won the National Book Critics Circle Award in 2000 and was a finalist for the Pulitzer Prize. Conover is also the author of Rolling Nowhere: Riding the Rails with America’s Hoboes; Coyotes: A Journey Across Borders with America’s Mexican Migrants; Whiteout: Lost in Aspen; and The Routes of Man: Travels in the Paved World. He regularly writes for the New York Times, Harper’s, the Atlantic, and many other publications.