The Polish Army Officer Who Conjured Proust in a Soviet Prison Camp

On Józef Czapski's Wartime Lectures

A titled aristocrat by birth, Józef Czapski first arrived in Paris from Kraków in 1924, a penniless painter at the start of a long career. (His family’s estates and large fortune had been seized by the newly amalgamated Soviet Union.) A great reader, he immersed himself in contemporary French writing. Proust, already legendary, had been dead for little more than a year. Randomly picking up one of the early volumes of À la recherche du temps perdu, Czapski was initially put off by what he found to be an excess of style, but trying again not many months later, in the aftermath of a failed romance, Czapski would find in Proust’s novel the intense release that he required. Burying himself in its pages, he developed a profound admiration for the work that would never diminish.

Over the years, his growing circle of Parisian acquaintances came to include several of Proust’s old friends. The poet Léon-Paul Fargue entertained Czapski with stories of the elusive writer who lived as a recluse (a recluse who liked, occasionally, to dine at the Ritz). François Mauriac, novelist and critic, welcomed the young Polish painter into a group taking up the cause of spirituality in modern art. Daniel Halévy, twenty-four years Czapski’s senior, had been the recipient of several audacious love letters from Proust while they were still schoolmates at Lycée Condorcet, as well as the subject of a purple poem called “Pederasty,” in which the 17-year-old budding writer praised his friend’s adolescent beauty and his “sweet limbs.” Czapski would remain a loyal friend of Halévy’s for over thirty years.

Proust’s spirit was perhaps most vividly brought to life through Czapski’s affectionate connection with Maria Godebska-Sert, known to one and all as Misia. A great beauty of Polish descent, Misia, the cherished confidante of Coco Chanel and Sergei Diaghilev, reigned supreme in the beau monde for many decades. An accomplished pianist who had known Franz Liszt and studied with Gabriel Fauré, she was a hostess of wit, intelligence, and charm, a source of envy and dismay to every fashionable Parisienne. Misia’s zaftig physique and stylish chic are immediately recognizable in dozens of portraits painted by her friends Édouard Vuillard, Pierre Bonnard, Auguste Renoir, Pablo Picasso, and Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec. Her first husband, Thadée Natanson, with his brothers, launched La Revue blanche, a sumptuously illustrated literary journal in whose pages their precocious friend Marcel Proust published his first writings. In À la recherche, Misia would be transformed into the exotic Princess Yourbeletie.

With a characteristic mixture of reluctance and determination, Czapski approached this paragon of high society to ask if she would consider hosting an event to benefit his small band of struggling Polish painters, each of whom dreamed of prolonging their stay in Paris. Heartily agreeing, Misia persuaded Picasso to help; together they drew up a list of distinguished guests to invite. Le tout Paris turned out for the occasion and the evening was a success. Artists’ models circulated among the crowd draped only in flowers; a raucous jazz band played until dawn. A swarm of grandees materialized, including the Comte and Comtesse de Gramont, the Duc and Duchesse d’Alba, and the Marquis de Polignac. The final volume of À la recherche had not yet been published, but Czapski found himself rubbing shoulders with the exalted denizens of Proust’s fabled Faubourg Saint-Germain.

![]()

Thirteen years later, the “low, dishonest decade” of the thirties came to an end. Czapski was back in Poland, a 43-year-old reserve officer defending his country from two invading armies. He was captured in a battle fighting the Germans, yet he and his regiment found themselves taken prisoner by the Red Army. This was unexpected; war had never been declared between the Soviet Union and Poland. Only weeks earlier, a secret alliance had been signed in Moscow by Hitler and Stalin’s ministers of foreign affairs, Joachim von Ribbentrop and Vyacheslav Molotov. The two great powers conspired in the destruction of Polish sovereignty. On September 1st, 1939, German armies crossed Poland’s western and northern fronts on land and in the air, followed on September 17th by nearly a million Soviet soldiers violating 900 miles of Poland’s eastern frontier. According to the terms of the covert treaty, the Nazis rounded up rank and file military prisoners for slave labor while the Bolsheviks laid claim to the Polish Army’s officer class, soon to be slated for execution.

“What Czapski remembered best was the quintessential book of remembering. Opening his mind to the narrative’s flow, whole scenes from Proust’s novel eventually resurfaced, in many instances nearly verbatim.”

Soviet authorities were determined to eliminate any threat to their dominion. In the weeks between April 5th and May 5th, 1940, roughly 22,000 Polish officers and cadets were murdered at several sites, on orders signed by Stalin and Lavrenty Beria, his chief of secret police. One prisoner of war after another was handcuffed and taken away to be shot with a single bullet in the back of the head. In remote locations, mass burial pits were dug by bulldozers every night for four weeks, piled with bloodied corpses stacked twelve high, then backfilled with dirt and planted over with pine saplings.

Inexplicably, Czapski’s life, and those of 395 of his fellow prisoners, had been spared. The surviving officers represented nearly all that remained of Polish military leadership. From various detention centers, these select men were transferred to one camp, a prison established on the derelict grounds of a dynamited Orthodox convent in Gryazovets, once a site of holy pilgrimage, 250 miles northeast of Moscow. The state security police, the NKVD, were their jailers; political operatives had supplanted army command.

Among the prisoners at Gryazovets nothing was known of the executions of their compatriots. Freezing, exhausted from overwork, on the brink of starvation, the men hardly thought of themselves as survivors. Referred to by the camp administration as “former officers of the former Polish army,” they struggled to keep their spirits alive and their morale strong, actively resisting the ceaseless attempt to break them down and convert them to the Bolshevik cause. For relief from the relentless misery, the men devised an ongoing series of talks to be given in the evenings before bunking down, each speaker choosing a subject dear to his heart. History, geography, architecture, sports, and ethnography were among the offerings by specialists and amateurs in their respective fields. Czapski volunteered to speak about the development of modern French painting from David to Courbet. In preparation for those talks, he formed the idea of devoting a series of lectures to Proust and À la recherche du temps perdu. The officers had no books or other source material with which to research their subjects. Czapski would later write, “Each of us spoke about what he remembered best,” and found that a prisoner’s constant state of vigilance was surprisingly conducive to the reclamation of memories.

What Czapski remembered best was the quintessential book of remembering. Opening his mind to the narrative’s flow, whole scenes from Proust’s novel eventually resurfaced, in many instances nearly verbatim. Pulling passages out of thin air, Czapski reenacted the very endeavor of À la recherche. “After a certain length of time,” he wrote, “facts and details emerge on the surface of our consciousness which we had not the slightest idea were led away somewhere in our brains.”

These memories rising from the subconscious are fuller, more intimately, more personally tied one to the other. I came to understand why the importance and the creativity of Proust’s involuntary memory is so often emphasized. I observed how distance—distance from books, newspapers, and millions of intellectual impressions of normal life—stimulates that memory. Far away from anything that could recall Proust’s world, my memories of him, at the beginning so tenuous, started growing stronger and then suddenly with even more power and clarity, completely independent of my will.

Czapski’s retrieval of Proust’s world “completely independent of my will” echoes the effort the adult narrator makes in À la recherche to identify the mysterious associations rising in him after having tasted a morsel of madeleine dunked in a cup of tisane. At first, all he can muster is a flimsy store of memories of childhood holidays at his Aunt Léonie’s, “as though all Combray had consisted of but two floors joined by a slender staircase, and as though there had been no time there but seven o’clock at night.” He’s trapped between actively encouraging the formation of a memory triggered by the taste of tea and cake, and passively accepting that it must materialize of its own accord, acknowledging that “the truth I am seeking lies not in the cup but in myself.” His senses ultimately triumph over his power of reasoning and the narrator is granted access to treasures buried deep in himself, yielding “all the flowers in our garden and in M. Swann’s park, and the water-lilies on the Vivonne and the good folk of the village and their little dwellings and the parish church and the whole of Combray and of its surroundings.”

Proustian methodology cannot be codified; Czapski learned to let the book come back to him without forcing it. Undertaking this process of reclamation, he came to understand that the true search of À la recherche is not for what one can remember, but for what one has forgotten. Samuel Beckett insisted that “the man with a good memory does not remember anything because he does not forget anything,” and claimed therefore that Proust “had a bad memory.” A good memory is “uniform, . . . an instrument of reference instead of discovery.” Like Proust’s journey, Czapski’s was one of discovery, and affirmation.

I recall with gratitude that around forty of my companions gathered for my French lectures. They came into that chamber at twilight, dressed in fufaika and wet shoes. I can still see them packed together underneath portraits of Marx, Lenin, and Stalin, worn out after having worked outdoors in temperatures dropping as low as minus forty-five degrees, listening intently to lectures on themes very far removed from the situation where we currently found ourselves.

Lost Time is a transcription of the talks he gave about Proust to his fellow officers. Having read À la recherche in French, he strove to recall it in French, and so gave his talks in French. Two friends from among the assembled listeners agreed to transcribe his talks some time after the lectures had been given to the larger group. Czapski dictated an abridged version to these two scribes. “In our canteen, in the great monastery’s refectory stinking of dirty dishes and cabbage, I dictated part of these lectures under the watchful eye of a politruk who suspected us of writing something politically treasonous.” Technically speaking, the book in your hand was not written by Józef Czapski. He never sat down to commit to paper the words that appear in this volume, but two separate handwritten dictations would eventually be converted into two sets of typewritten pages.

Czapski’s talks, and our knowledge of the circumstances under which they were given, have been handed down to us in this form. Further details remain difficult to verify. We know that Soviet censors monitored all public gatherings in every prison camp, disallowing the presentation of any potentially seditious (i.e., anti-communist) material. Any spoken text had to be submitted in written form for prior approval. It seems highly unlikely that this text would have been handed to a censor for scrutiny because it could not be expected that a Soviet functionary would be able to read French. And we know from Czapski that this text was transcribed after the fact of his having given the lectures, not before. How was this procedural detail overcome? Over how many days or weeks did he give his lectures? How many did he give in all? “I dictated part of these lectures,” he wrote. How much more material was there in his original presentations? When were the handwritten transcriptions typed up, where, and by whom? A typewriter would not have been available to prisoners in the camp. How did these pages, in any form, manage to leave the USSR, and in whose possession? Questions pile up, one uncertainty proposing another.

![]()

He chose a casual, conversational tone for his talks. Wearing his learning lightly, he didn’t burden his listeners with an excess of esoteric knowledge. Nevertheless he was speaking to a cadre of exceedingly well-educated men; he could slip in a quotation from Athalie, Racine’s final tragedy, with full expectation that it would be familiar to his audience. His touch was subtle and sure, tempered with humility. He expertly choreographed the thrust and parry of two distinct narratives in his talks—the novelist’s and his own. Recounting his first reading of Proust’s novel in the spring of 1926, when he had been suffering from typhoid fever and heartbreak, he claimed:

I was almost drowning in Proust. I had gone to stay with my uncle who at the time was a professor at the University of London. I lived at his place, a small townhouse with a small garden. I would spend all day stretched out on a chaise longue, baking in the sun. There I opened Proust, beginning with Albertine disparue, and plunged into his work. I read him all the time.

The bleak surroundings at Gryazovets differed radically from the sun-dappled backdrop of his early enthusiasm. Czapski’s determination to engage his fellow prisoners in so unlikely a pairing of content and context reveals a good deal about his own buoyant character and spirit. Who, from the outside, would ever conceive of Proust’s stories of the supremely privileged as a subject suitable for an audience of famished, lice-ridden, frostbitten prisoners of war huddled together in bombed-out buildings?

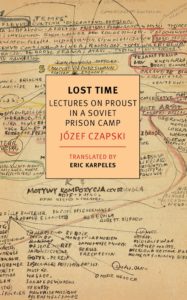

The lectures Czapski gave were unscripted. In preparation, he mapped out a cosmology of Proust, summoning his considerable skills as a visual artist to create schematic drawings in a series of prison notebooks. Intended to be used as aide-mémoire, the sheets he covered with information did not represent any kind of text to be spoken; each page was a carefully constructed nesting ground from which ideas might take flight. The pages are a hybrid of writing and drawing, of thinking and composing. Part blueprint, part stimulant, they represent the frenzied order—or the ordered frenzy?— of his cluttered, cultured mind. Nearly indecipherable at first glance, they gradually reveal their purpose and help us better understand Czapski’s plan of attack. Calling on deep reserves of historical knowledge, he put his critical thinking skills into play and hand-lettered several wide-ranging conceptual diagrams. And though his talks were to be given in French, his diagrams were primarily written in Polish. In pencil, colored pencil, watercolor, and ink, the diagrams are packed with references to artistic movements, historical personages, and fictional characters; with the names of writers, painters, philosophers, and musicians; with Proustian icons and biblical allusions. As if throwing a cocktail party for notable ideas, he invited critics, artists, designers, and aristocrats to mix with literary terms (realism, naturalism, romanticism), abstract categories (love, life, compositional methods), and decorative arts (stained glass, still life, Gothic sculpture). The Ballets Russes and cubism appear, as well as Goethe’s autobiography, Dichtung und Wahrheit (Poetry and Truth). A tiny sketch of a haystack is meant to prompt his recall of the phrase “si le grain ne meurt,” a reference to John 12:24, and the title of André Gide’s biography: “Except a grain of wheat fall into the ground and die, it abideth alone; but if it die, it bringeth forth much fruit.” These lines, which appear in the very last pages of the very long novel, would figure in Czapski’s discussion of the foundations of creativity. His far-flung thoughts on Proust, abidance, and death stretched across time from the Gospels to Gide.

“As if throwing a cocktail party for notable ideas, he invited critics, artists, designers, and aristocrats to mix with literary terms (realism, naturalism, romanticism), abstract categories (love, life, compositional methods), and decorative arts (stained glass, still life, Gothic sculpture).”

Next to the words “grandeur and misery” written in Polish, the word “resurrection” is inscribed in Cyrillic script in the upper right corner of one diagram. (Having passed his baccalaureate in St. Petersburg, Czapski was fluent in Russian as well as French, Polish, and German.) “Resurrection” is a word that recurs throughout his talks. He cites Tolstoy’s late novel Resurrection as an example of a work whose moralizing concerns Proust considered antithetical to art. The act of resurrection figures prominently in his retelling of the story of the death of Proust’s character Bergotte, a writer whose life and work flash before his eyes as he is dying. But perhaps most significantly, in summing up his talks on À la recherche, Czapski presents resurrection as the engine that drives Proust’s poetics of memory, fueled by the philosopher Henri Bergson’s ideas on intuition. Certainly, involuntary memory is in itself a kind of resurrection, bringing the past back to life, “taking on form and solidity.” The narrator of À la recherche, exposed to “the existence of a realm of awareness beyond the ordinary” in the novel’s final volume, is finally able to recognize his vocation as a writer. He sees that, in his role as an artist, he has the power to save the fragile, foolish, mortal beings surrounding him in the ballroom of the new Princesse de Guermantes. They will all return to life in the book he now intends to write, resurrected from his own wasted years by his newfound powers of observation. In a similar way, Czapski’s eventual decision to publish his lectures served to rescue his fellow prisoners from oblivion and, by extension, revive the memory of their murdered comrades. Czapski would continue reading Proust for decades; every reading brought his lost friends back to life.

Czapski’s talks introduced a breath of humanity into an inhuman environment. The intent of the Soviets was to destroy any vestige of Polish identity these men clung to, to expunge any trace of freethinking in them, whether political, intellectual, or personal. The strategy was to supplant one belief system with another by means of force—to shatter the prisoners’ ideals, then reconstruct them with the glue of communist ideology. This process failed. Despite an arsenal of brutal methods, psychological intimidation, and physical threats used against them, the cadre of Polish officers at Gryazovets refused to succumb. Initially taking up À la recherche du temps perdu on the basis of aesthetic inquiry, Czapski soon recognized its value as a practical template for survival. The lectures offered a viable counterpoint to the repeated interrogations the men were forced to endure. His lectures were an act of resistance, stimulating the recovery and retention of personal memories that could protect and defend his colleagues from the attempt to deprive each of them of a sense of self.

The very words temps perdu, lost time, must have resonated with heightened significance. Czapski’s lectures on À la recherche du temps perdu may have reinforced the poignancy of his audience’s sense of loss, but the subtext was a rallying cry for making the most of the time at hand. Presenting Proust as a bulwark against fear and desperation, he shepherded his companions towards the French novelist’s promise of recovery, of le temps retrouvé, towards the hope of finding time again.

__________________________________

From Lost Time: Lectures on Proust in a Soviet Prison Camp. Translated from the French by Eric Karpeles. Used with the permission of New York Review of Books. Copyright © 2018 by Eric Karpeles.

Eric Karpeles

Eric Karpeles is a painter, writer, and translator. His comprehensive guide, Paintings in Proust, considers the intersection of literary and visual aesthetics in the work of the great French novelist. He has written about the paintings of the poet Elizabeth Bishop and about the end of life as seen through the works of Emily Dickinson, Gustav Mahler, and Mark Rothko. The painter of The Sanctuary and of the Mary and Laurance Rockefeller Chapel, he is the also the translator of Lorenza Foschini’s Proust’s Overcoat. He lives in Northern California.