Before I met Viridian, I didn’t know any poets, any real poets. “Real” meaning other people agreed that you were a poet, and published your poems in books and magazines, and made a fuss over you. Was she a famous poet? What did that even mean? What was a poet anyway? Was that a trick question? I didn’t even know what to ask.

Viridian hadn’t ever been on television, which is usually what famous means in America. Neither she nor any of her circle would have expected such a thing. Every so often a poet might be singled out and elevated by reading at a presidential inaugural, or the dedication of a monument, but that wasn’t exactly steady work. People said that books of all sorts were losing ground to videos and podcasts and blogs. The whole enterprise of poetry had been pushed into a kind of outer orbit, unseen but still capable of exerting a gravitational pull, a slow shaping of thought and language that people call culture.

Of course, the poets themselves kept track of their prizes and awards and who had the hot hand. They gossiped and nursed intricate grudges among themselves. They harbored secret hopes of literary immortality, of their poems bursting into bloom a hundred years or more from now, like fireweed. And who was to say it wouldn’t happen for them?

But these were all things I came to understand later. At the beginning, she was just Mrs. Boone, and I was there to put in some plantings she wanted.

What did I know about poets? Nothing, or maybe less. None of my schooling had exactly set my soul on fire when it came to literature. Poets wore berets and drank too much—this at least was often true—they lived in Paris or New York or they were already dead, they wrote about going down to the sea again, to the lonely sea and the sky, or else they wrote in scrambled words and sentences that an ordinary person couldn’t follow, although they were no end impressed with themselves. I’d gotten along just fine so far without poetry.

I was so perfectly ignorant, an irresistible blank slate. No wonder everyone took it upon themselves to try and mold and educate me.

*

My boss, Rick, was going to meet me at Mrs. Boone’s house so he could introduce us, as Mrs. Boone did not want people just showing up. “Even girls,” Rick said, one more of his helpful remarks. He thought he deserved all kinds of credit for hiring me in the first place.

I had to be in San Rafael to drop off a part for an irrigation system, so it was no problem to head out west to Fairfax, where Mrs. Boone lived. It was May and the sky was already blue and hot, even early in the day. I hoped I could get the job knocked out before the air really started to cook. Northern California is supposed to have this perfect climate (in between mudslides, forest fires, and earthquakes), but a dry heat is still heat. It could get really hot in Fairfax, where the hills kept the cooler ocean air from piling in. Thirsty deer came down from the higher ground and munched the roses and vegetable gardens into stubs.

I reached the little downtown, with its yoga studio and coffee shops and ice-cream shop and brew pubs and natural food grocery. Fairfax used to have a doped-up, pleasure-seeking hippie vibe, and there was still an air of that left, even as the price of real estate had soared. More shiny new restaurants had opened, more of the old, haphazard houses had been torn down. The vibe was now more like expensive mindfulness. Green Party candidates won elections here; they actually ran things. Nationally owned chain stores were banned, as were pesticides, plastic bags, and Styrofoam. Fairfax was an official nuclear-free zone, for God’s sake. Like nukes were some pressing local threat.

I lived in Petaluma, which was less than an hour away but was all box stores and fast food. It was fine with me. It felt more like the real world.

I took a couple of wrong turns off Bolinas Avenue through the flat and sunny parts of town, before I got the GPS on my phone to stop squawking at me and I headed uphill. The road climbed and curved along a canyon, and on its outer edge people had built homes into the hillside below. They parked on pads built out along the roadway and walked down to their front doors.

Mrs. Boone’s house was on the opposite side, on the hill itself, at the end of a steep lane. A gate in the board fence stood open. I nudged the truck through the gate and pulled over to one side of a wide, brick-paved courtyard. Rick wasn’t here yet, so I stayed behind the wheel to wait for him.

The house was brown-shingled and sprawling, two stories, and it looked like it had been here awhile without much updating. Parts of it seemed to have been built out as additions. One wing ran back to connect with a barnlike garage, while another made up a kind of breezeway with a screened porch at its end. For a hillside house, there was a good amount of sun. The courtyard had a center island planted with agapanthus, it looked like, along with poppies and succulents and lavender. Someone had made an effort at plantings around the house foundation. There were overgrown rosemary bushes, daylilies, Mexican sage, plumbago, and a section where trailing nasturtiums fought with foxtails.

Through the big windows of the breezeway, I saw a flat space of sunny lawn, with deer fencing all around. It enclosed a square of vegetable garden, a few fruit trees, and a great many weedy, terraced beds. Beyond that, redwoods and ferns and the green tangle of woods. The gardens had the look of the house itself, things thrown together and improvised over time.

Rick arrived ten minutes later. His big Ramcharger truck came close to knocking the gate off its hinges. I rolled my eyes at him to make sure he knew I’d noticed. He took off his baseball cap and ran a hand over his black hair to slick it in place. He was always convinced that his sweaty charms impressed the lady clients.

“Oh Ricky,” I said. “Hold me tight.”

“You’re weird, Sawyer.”

“Why thank you.” He shook his head. “Nice attitude.” His real name was Ricardo, but he thought he’d get more business if he sounded white.

Rick rang the bell, which sounded somewhere deep inside the house. “Any special instructions?” I asked while we waited.

“Try not to screw up.”

I might have said something smartass back at him, but the door opened and Mrs. Boone, I guessed it was her, stepped out onto the front porch. She had long gray-and-silver hair brushed straight back from her forehead and standing out like a lion’s mane. She was barefoot. She wore loose white linen pants and a blue knee-length top with wide, drooping sleeves. I saw older women wearing clothes like these in Marin, equal parts yoga practice and Star Wars costuming. I wondered how old she was. Sixty? Seventy? Then I found myself asking another question: whether she had been, or was perhaps still, beautiful.

All this in a moment, only as long as it took Rick to say hello and tell her we had everything she’d ordered. “This is Carla, she’ll be doing your work today.”

I don’t remember Mrs. Boone saying much—hello, probably— looking me over while I tried to appear obliging, capable, harmless. She had a wide forehead, and her blue eyes were wide-set also, and there was something about her eyebrows that made you think of birds, the wings of birds, although not until later when you tried to recall what in her face had struck you.

And what would anyone have seen in me? I was tall, a full head taller than Rick, which was why I got away with giving him shit. I wasn’t one bit big or muscled, but I could lift my share of loads. My hair was tied up in a knot under my canvas hat. I wore shorts and work boots and my skin was red-brown from sun and full of different half-healed scrapes and bites. At least before I started working this morning, I had been clean.

Mrs. Boone went back inside, and Rick and I unloaded the nursery stock from his truck. There were rhododendrons and hop bush and guara, some dwarf cypress, and salvia and shasta daisies. These were all meant to go in the back of the property, in the terraced beds. Rick went over the plan with me, gave me a little more grief, and drove off.

I’d been working for Rick for almost a year now. It wasn’t my dream job, though I couldn’t have said what was. After graduation I took some courses at Santa Rosa JC, but I have one of those brains that doesn’t process words on a page very well, and I hated composition classes and anything else that was reading-heavy. I was considered “intelligent” (which was something that seemed to be used against me), but also an underachiever. And although the brain wiring was beyond my control, everyone seemed exasperated with me. They believed I was not trying hard enough, not applying myself. My mom kept telling me to go into a medical field, like taking X-rays or working in a lab, but those jobs just screamed boredom. At least, working for Rick, I was outside every day, seeing actual results, things growing. I didn’t have to dress up or put anything on my face except sunscreen.

I lived with my boyfriend, Aaron. On weekends, we went out to listen to music, or maybe we’d take his dog, Batman, to the beaches or go camping. We were good together. I figured that one of these days we’d get married, and life would fall into place for us without a lot of special effort, the way it happened when you loved each other. We were lucky to have found each other and we knew it.

But from time to time, I was overcome by a sadness or strangeness, a feeling of too much feeling, if that makes sense, of standing just outside of something desirable and urgent and important. And then I had to get a grip and tell myself, as my mother surely would have, that I must not have enough real things to worry about.

__________________________________

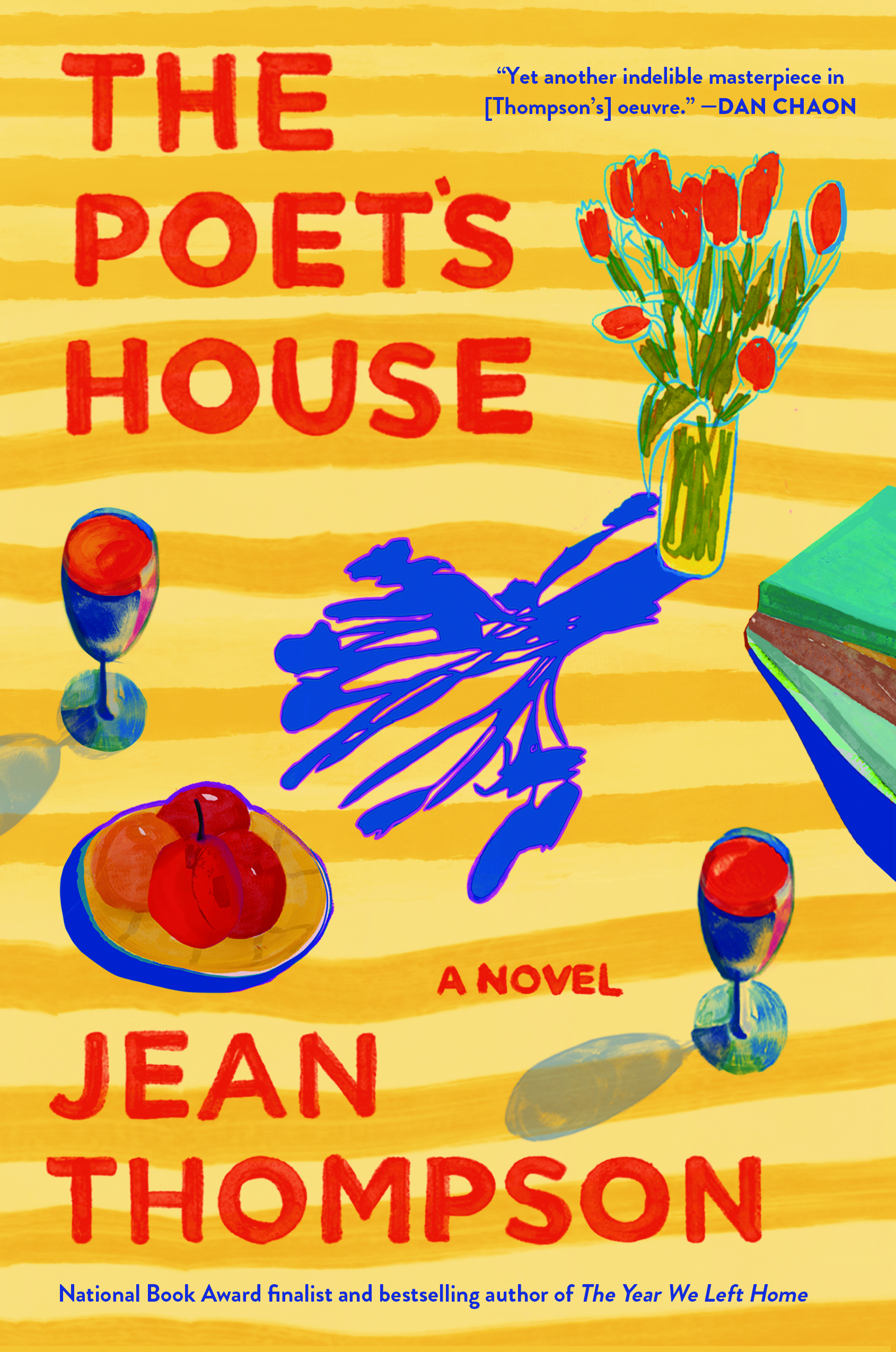

From The Poet’s House by Jean Thompson. Used with permission of the publisher, Algonquin Books of Chapel Hill. Copyright © 2022 by Jean Thompson.