The Pleasure of Taking the Long Way: On Puzzling the Route to a Poem

Lauren Camp Considers the Value of Spending Time in Astonishment

In so many ways, the things we have to do in our lives have to be done right. So much seems to be about speed, utter clarity, and efficiency. I am bored by all of that exactness. Perhaps this is one of the reasons poetry is so appealing. It’s a time of extreme permission—at least the way I teach it and practice it myself.

Sometimes my emerging students say they don’t like revision. I’ve learned this often means they don’t know what to do to their poem. When they re-read what they’ve written (often within days or a week of writing it), they are still within the ecosphere of their initial impetus.

Class after class, I show them how to widen, add new experiences, move off the predictable path. As they claim that generous space to experiment, they see how later iterations can be more magical than where they started.

Then, too, there are some students who are most comfortable thinking the work is polished—and why can’t it just come out that way?

I don’t know about you, but I don’t believe what I write at first is ever phenomenal. (Okay, maybe one poem a million years ago…) That’s fine with me. If it were, I couldn’t stay in the making.

To me, revision is a liberation. I get to let go of control for this one thing in my life. I am happiest when I have to disassemble and reconstruct a poem because that means I’m not limited by my mental map. Instead, I gleefully entangle in the wayfinding. Ahh, what a relief such slowing down is!

Over the years, I have gotten more interested in building multiplicity into my writing. I’ve been experimenting with how much I can pour into the poem. Another element? Sure. A psychological worry? Why not? Or maybe even a whole separate storyline. If I am too obedient to the narrative and direction I started with, I can only write what I already hold clearly in mind. I don’t want it to be that easy. To be honest, I don’t really want to finish—at least not for a while. Waiting is an essential part of the writing process, and there is no way to speed that step. It takes the time it takes to ponder, or to move off from the poem. To wait for clarity of direction.

A poem that was going to be about how pretty those flowers are—which is, admittedly, a rather dull concept for a poem—becomes a poem that looks at the passage of time, or grief, or… who knows?I’ve also learned that, to go forward, I may have to go sideways. Untying the creative knot is, in itself, a kind of direction. The goal is to rely on what I know only to see where it could point me, then I want to escape that. I want to redirect the writing many times, until I reach a place I don’t quite recognize. It will have vibrations of what I thought I knew, but also other influences. I want to make a new landscape of marks.

I may have to pull the work entirely apart. Demolition is allowed—and sometimes fun. (To appease the part of me that wants to feel I’ve done something useful, I try to keep at least one line from a draft I’m demolishing—and appreciate it even more.)

Revision, the way I choose to do it, rarely hews close to the existing text. When I return to the work after some time has passed, I’ve filled my brain with other books, music, storylines, news bits. The season has changed, and my mood. I want to push the work in some new direction. I stretch and tighten the work, reading it aloud again. Sometimes, when I look back at the many drafts I’ve done, I’m amazed at how far I’ve veered from the course I initially set. A poem that was going to be about how pretty those flowers are—which is, admittedly, a rather dull concept for a poem—becomes a poem that looks at the passage of time, or grief, or… who knows?

In teaching, I offer examples and talk to them about punctuation, what length of line does, what a stanza can feel like. I engage them in the thinking behind an author’s decisions by the and ask them to look at their own work through these lenses.

I build a safe space for students to generate work. No one in the class can make judgments on what gets written. There is only acknowledgment.

Let’s agree, I say, that the initial draft is great, whatever you’ve managed to lure into it. But it doesn’t all have to stick. You are looking for the way. You don’t yet know it—and you don’t need to. All you need do is demand more than your starting point.

I request that students take a single, small step. I ask them to rearrange or to remove one line before the next session, and they return and say they did much more. I use the word might. I ask questions. It’s so exciting to see them learn to trust that what is there could shift: the line, the syntax, the structure. What if you whittle the adverbs, sharpen the sonics? Learn to use your tools by using them. I am forever asking, how would this work? I don’t know; try it. I don’t have an agenda for their work, only my own. I want them to push further. I help them to see how much bigger their map can be.

For a long time, mystery can be the place to be. Let’s not rush to the end. I’d rather we spend our time inside the astonishment.

__________________________________

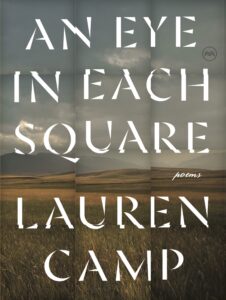

An Eye in Each Square by Lauren Camp is available now via River River Books.