The Painting That Changed My Life

On Art, Grief, and Amy Pleasant's After the Death

1. The National Museum of Women in the Arts, Washington, D.C., 2005

In the fall of 2005, I was asked to write about a painting called After the Death. I had recently been promoted to head editor at the National Museum of Women in the Arts, but I wasn’t really qualified for the job. I was 24, interested in art but not formally trained. I did not love this painting yet. I did not even like it. I didn’t understand it at all. But it was going to be exhibited at the museum, and I was required to produce 600 words about it for the members’ magazine.

This was before digital images were abundant, and I was given a tiny slide to study. I stared at that slide through an old-fashioned viewer for hours, my eye sockets pressed into the plastic binoculars. The effort was pointless, like staring at the empty boxes of a crossword puzzle I had no hope of solving.

The painting depicted 30 scenes of silhouetted figures, organized on the canvas like a series of Polaroids. Some silhouettes were inky black, sharp against the yellow-green background, and some were greyed out, as though drawn and then erased. The story was baffling. Were the cartoony figures meant to be the same person, or did they represent different people? I couldn’t tell. The characters read letters, packed (unpacked?) boxes, entered (or maybe left) through a mysterious door. One scene revealed a steep staircase beyond the door. Had someone fallen down that staircase and died? The painting was titled After the Death—were the shadowy figures ghosts? Was the letter a suicide note? Where did the narrative start, and where did it end? The scenes didn’t go in any kind of an order I could discern. The distance and perspective kept shifting, reframing the scene from new angles, zooming in and then out. But even the close-up images didn’t offer enough clues to the mystery of this story.

My article was going to be a disaster.

But my article was not a disaster. The museum’s curator of contemporary art—a German woman in her early forties named Britta who I found both chic and intimidating—agreed to take time out of her schedule to discuss the painting with me. She pointed out the gridded structure, which she thought might be borrowed from a storyboard or a comic book. This structure was important, she said. It implied a linear story, a narrative that could be read from start to finish. But here, it seemed to be fractured. Britta honed in on the contrast between the linear grid and the ambiguous narrative. She suggested I think about that. The tension might be the key to understanding the work.

That first whiff of insight is such a specific, powerful high. That moment when the confusion subsides and the observer floods with wonder, washed with a wave of understanding. It doesn’t last long—in the next moment, intellect wrestles inspiration into coherence and logic takes over. We begin to name things, to make sense of them, to build upon our insight. This act of articulation is, of course, the joy of writing. But it is analytical, an intellectual pleasure. For a few seconds at the beginning, there is just the pure joy of enlightenment.

I saw what Britta was talking about, and then I began to see other things in the painting. My father had died a few months earlier. He had been ill with cancer and lived many years beyond what was expected. I was grieving, but not in a dramatic, raw way. My experience of grief was defined more by things I didn’t have the energy to deal with than by wrenching sadness. I ate my meals, went to work, saw friends. I just did it all with a tedious droning in the background for a while. In fact, grieving was so tedious that I would have welcomed a little drama—a satisfying meltdown or a family blowout. Some kind of climax, like in the movies. But there was no satisfying narrative arc to my father’s death, or to the months, the years, that came after. Grieving was a slow, recursive process that seemed to move backwards or in circles as much as it moved forwards.

I connected with the painting’s insight. The tension between the relentless march of time, represented by the storyboard structure, and, in contrast, the elements of life that can’t or won’t move at that speed, those stories that refuse to be framed by the traditional narrative arc, represented in the painting by the fractured narrative and repeated images. The painting insisted on the mundanity of death, and of grief. The stark truth that someone else’s death will always be, by definition, anticlimactic—that there will always be an after to a death because the laws of time require that our own story continue while theirs fades into the past. The figures in After the Death were living through the mundane anticlimax: packing boxes, sorting artifacts, carrying on. I related to this tedium. It felt honest to me.

“There was no satisfying narrative arc to my father’s death, or to the months, the years, that came after.”

I left my final version of the article in Britta’s mailbox for approval before publication. She returned it with a generous note saying it was good, much better than the first draft she saw. That I must have worked very hard on it.

I had.

Excerpt from the Fall 2005 issue of Women in the Arts magazine.

Excerpt from the Fall 2005 issue of Women in the Arts magazine. © National Museum of Women in the Arts, 2005.

Reprinted with permission from the National Museum of Women in the Arts.

2. Jeff Bailey Gallery, New York, New York, 2008

About a year after I moved to New York, I emailed Jeff Bailey, the gallerist who represented Amy Pleasant. I explained that I had written about her previously, that I was a fan. I asked if I could see more of her work sometime. I was upfront: I wasn’t in a position to buy anything. This was just for love of her work. Jeff graciously invited me to come over, anyway.

He met me in his Chelsea gallery space one night after work. Walking the long blocks from the Eighth Avenue A train to Chelsea—not as a tourist, but as a New Yorker—was thrilling. I had moved to the city because I wanted to work at a big magazine. The New Yorker was my first choice. I got an interview there but not a job and instead, needing to pay rent, accepted a position on the other side of the editorial spectrum: as a copy editor at Ralph Lauren, where I proofread marketing materials. Though the work wasn’t particularly creative or challenging, my first months in the fashion world left me feeling even more out of place than I had first felt in the museum world. I wasn’t as stylish as my co-workers and I knew nothing about the industry. But I liked learning about fashion, thinking about color and texture and silhouette. It wasn’t so different from studying art. Also, I was exhilarated to be living in New York. I liked the sound of my boots clicking on the sidewalk as I hurried to be on time for my appointment.

It was my first time in a New York gallery and it was exactly as I imagined it: industrial, nonchalant, intimidating. But Jeff was warm, a gracious, if inscrutable, middle-aged man with white hair and an elegant manner. He showed me several of Amy’s paintings, all of them storyboards on giant six-by-five-foot canvases, like the one I had come to love.

Jeff was originally from Birmingham, Alabama, he told me. He had discovered Amy through a friend at the Birmingham Museum of Art, who recommended her as one of the most promising young artists in the city. When Jeff saw her work, he agreed with his friend’s assessment of her talent. He thought she was an especially good colorist.

Toward the end of our visit, I asked him what had become of After the Death. He told me he had purchased it himself. It was hanging upstate, near the small town of Hudson, in the weekend house he owned with his partner.

3. Jeff Bailey Gallery, New York, New York, 2009

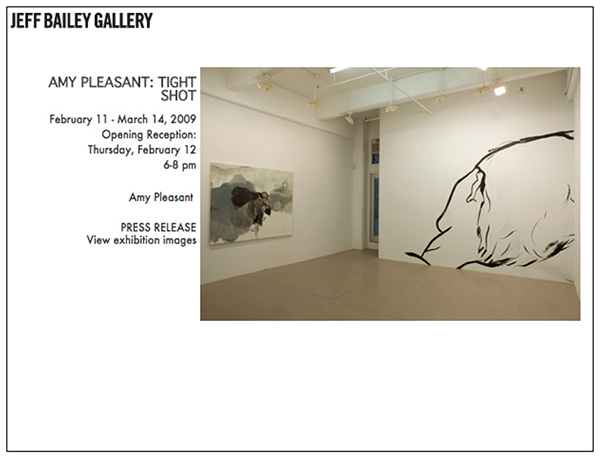

Jeff added me to his mailing list, and in January 2009 I received an invitation to attend the opening for Amy’s latest show, Tight Shot.

Invitation to the opening of Amy Pleasant’s exhibition Tight Shot, February 2009.

Invitation to the opening of Amy Pleasant’s exhibition Tight Shot, February 2009. Courtesy of Jeff Bailey Gallery.

I had learned by then that Thursday nights are when all the galleries host openings and offer free wine, so I expected Chelsea to be crowded. Jeff’s loft was predictably packed when I arrived. I didn’t mind the crowds, though. I had visited many galleries by then. Most of them remained empty most of the time, aside from the assistant, and I found the presence of just one other person in those not-quite-empty galleries distracting. In a crowd, it was easier to look at the work without feeling self-conscious.

It had been a year since my first visit. I’d relocated from the windowless room I’d rented when I first moved to Brooklyn into an apartment on a different floor of that same building, where I had a real bedroom. I had a smart new haircut. I’d figured out a look that worked for me, and, probably not coincidentally, been promoted at my job. I was writing a culture and style blog for the brand’s website, social media stuff, some marketing copy. I liked my work and felt like I was a part of the energy of the city. I was doing what I came to New York to do.

I took my time walking around the room. Amy had moved away from the storyboards, it seemed. She was no longer working with scenes and breaking them into narrative fragments that comprised a whole. Instead, she had blown up a single moment, examining it from different angles in a series of enormous close-ups. A couple kissed, and Amy imagined it from three perspectives on three separate canvases. I liked these new images. They were still mysterious, but the close-up scale made her figures feel more like developed characters. I liked imagining their lives.

There was a break in the crowd surrounding Amy, and I walked over to introduce myself. Though we’d talked on the phone when I interviewed her in 2005, I’d never met her in person. She was warm and bubbly, tall and slender with long hair and a soft Southern accent. She wore high heels, but no makeup, and she laughed when she admitted that though she’d attended school in Chicago and was familiar with New York, she felt a little overwhelmed by the city after living in Birmingham for so long. She complimented my hat, and though I know Southern women say that kind of thing out of training, she seemed genuine. I liked her.

After the show, I emailed Jeff to tell him how much I enjoyed it. My grandmother—my father’s mother—had recently died and left me a little bit of money, and I told him I’d be interested in possibly buying one of Amy’s smaller pieces. I knew this was not a practical use of money, but it felt fitting to me to spend my inheritance this way. There had been some smaller drawings on display at the show and I thought maybe I could afford one of those.

Jeff wrote back to say that he and Amy had discussed things. They knew I loved After the Death; if I wanted to purchase that piece, Jeff would take it out of his personal collection and acquire another work in its place.

The painting cost $9000. Until that moment, the most money I’d ever spent in a single sitting was on a new couch for my new apartment. It cost $1000 and was the first piece of new furniture I had purchased from somewhere other than IKEA.

I felt queasy as I wrote the check. But I never questioned whether I was going to do it.

4. Brooklyn, New York, 2012

When friends came over to my Brooklyn apartment and seemed interested in Amy’s painting, I usually asked them what they thought it might be about before telling them the title of the work. It surprised me how many people thought it might be about moving. All those boxes, I suppose. And though I had never looked at it that way on my own, the interpretation struck me as insightful. In a way, the painting is very much about moving: about the blurry line between the end of one thing and the beginning of another; about how time ushers us relentlessly forward; about the ways we move on from the past; about how we grasp for moments in hindsight to make sense of our own stories.

In the fall of 2011, I moved apartments and jobs. I felt established enough in my career to buy a small condo in Brooklyn, not far from the building I’d been living in since my first weeks in the city. But I also felt a pull towards change in my work. I no longer felt satisfied writing from a brand’s perspective; I wanted to write about my own ideas. I left Ralph Lauren for a job as the editor-in-chief of a national fashion news blog. News blogging was another new industry to learn, but it would give me the freedom to choose and write my own stories. I hoped the change would help me grow as a writer and editor.

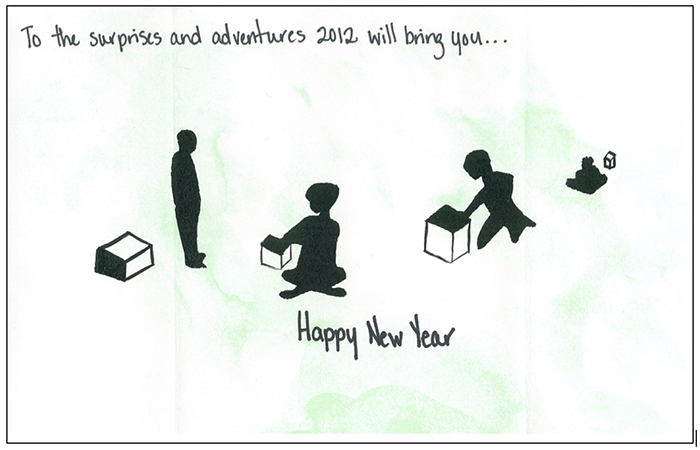

I like to make my own holiday cards and that December I spent a weekend re-creating images from Amy’s painting to send to my friends and family. I painted cheap cardstock with a yellow-green watercolor wash for the background and then stenciled silhouetted figures in black acrylic paint on top. I thought After the Death was an interesting new-year metaphor, an image about time and movement to offer my friends and family as we all ended one year and began the next. I sent out my best wishes for 2012.

Holiday card, December 2011

Holiday card, December 2011

The card embarrasses me now: the awkward, alien-headed imitations of Amy’s stylized figures, the one-note cheerfulness of the tone. Looking back, I can see the discrepancy between the way I was feeling at the time and the way I was trying to sound. In reality, I was running low on the steely strength necessary for life in New York by then. I did not love my new job. I worked too much. I had stopped going to museums and galleries. Amy had a show that fall, but I was too busy or too tired, or both, to make it. Her work, like most of the things I loved, was being crowded out by my own work, which felt meaningless most of the time. Though I was writing my own stories, they were still filtered through the perspective of a brand and a voice that wasn’t my own. Most of them were meant to entertain the reader for a moment and then be forgotten. Posted, and then replaced by a more recent story, never revisited, in a never-ending scroll of news.

I suspect that I tried to write about Amy’s painting again at that moment because I was beginning to question whether I really wanted the life I’d created for myself. I can see myself trying to force an insight. I offer advice, to myself as much as to my friends—not to be afraid when life doesn’t move forward, when it overlaps and circles back around in unexpected ways. And then, in the same breath, I refuse to do any of that. I insist on the neat story of my own life. A natural progression of success, confidence, happiness. I am telling a narrative of my life that moves indefinitely forward—an “awesome adventure,” an arc with a clean resolution. There is no room here for backtracking, or revisiting, or thinking in circles.

“Amy’s work, like most of the things I loved, was being crowded out by my own work, which felt meaningless most of the time.”

But the questions I pose rhetorically in this letter—Was I in the right place? Was I making the right decisions? Was I doing the right work?—are the kind that refuse to be left behind. Ultimately I had to face them. When I did, the answer was no, not anymore. I left my job, left my new apartment, left the city for good in 2013, a year and a half after I sent this card.

5. Jeff Bailey Gallery, Hudson, New York, 2015

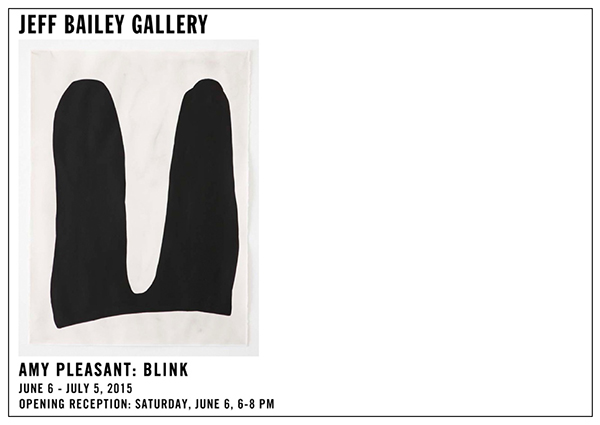

I got an invitation from Jeff and decided at the last minute to attend the opening of Amy’s latest show. I hadn’t seen her in years and I was curious about her new work. I drove from Virginia, where I had enrolled in a creative writing program, to Hudson, New York, where Jeff had relocated his gallery. My AirBnB was only a few blocks away from Jeff’s gallery, and I walked over after browsing the antiques stores on Main Street. I could see immediately that Amy’s art had changed a lot. The narrative element was completely gone now. There were no stories, no characters—only fragments of body parts. I surprised myself by feeling betrayed, and I realized with a shock that I was possessive of her work. I hadn’t wanted it to change.

Invitation to the opening of Amy Pleasant’s exhibition Blink, June 2015.

Invitation to the opening of Amy Pleasant’s exhibition Blink, June 2015. Courtesy of Jeff Bailey Gallery.

Jeff’s new upstate space had a beautiful back yard. Most people were hanging out back there, near the free wine. I had the first room of the gallery to myself and spent a half hour looking at Amy’s new collection. After some time, I realized that her work had not so much changed as evolved. Her interest in gesture—which she explored in the open-ended narratives of her storyboard paintings and later in the iterative characters of her 2009 show—had focused. The scope of her images had winnowed over the years from scene, down to moment, down to just an isolated body part.

Her scale and palette had narrowed, too. There were a few large canvases, like the one I own, in this show, but mostly the works were smaller, painted in a minimalist range of blacks and whites. Shape and contour were emphasized over tone. The tilt of a head or the curve of a shoulder. The flexing of a foot. The images were asking the viewer to consider what we understand about a narrative from just a few carefully drawn lines.

I began to warm to the new work.

Amy came to find me. We hugged hello and chatted for a while. I asked her which was her favorite piece in the show. She told me it was the one that also happened to be my favorite, a grid of black lower-body silhouettes on a white background that examines thighs from every angle: head-on, in profile, prone. Amy said she was interested in the way even a still body part can evoke movement and gesture. What just happened a second ago; what is about to happen. The way the world moves when we blink.

As we talked, Amy’s son came in search of her. He had a smattering of freckles across his nose and wore an untucked soccer jersey. He was very obviously bored. “What are those?” he asked his mother, pointing to a painting called Bend, the image from the invitation, which shows the silhouette of a lap from the sitter’s perspective. “Those are legs, honey,” Amy told him. “Oh,” he said, pausing a moment. “They look like upside-down pants.”

When I interviewed Amy for my article back in 2005, we set the call for nighttime, after her two young children had gone to sleep. I remember the conversation being interrupted at some point by a toddler’s voice in the background. Her son had emerged from sleep and needed to be coaxed back into bed. This must be the same child, a decade later. The way the world moves when we blink, I think. And suddenly I flooded with wonder. I understood the work. The meaning was in the fragment, I realized. Narrative seduces, comforts. It offers the definitive story about who we are, comprised of moments carefully selected and bound together by threads of our own invention. But we are none of us capable of remembering life in real time, playing it back second-by-second like a video; we can only hold on to fragments of memories. Meaning manifests in fragment because memory does. And because fragments exist in isolation, rather than in relation to what came before and what came after, we engage in a constant process of revisiting, reinterpreting, repurposing, and reorganizing memories. It’s in this restless collaging that we find insight.

6. Rehoboth Beach, Delaware, 2016

It’s been 12 years, almost exactly, since my father died. He died here, in the beach house my parents built for their retirement, just a few months after they moved in. It was a brand new house then. When they moved in, on Memorial Day, he was well. But throughout that summer, as my mom unpacked and decorated, he moved quickly from health into weakness, and then into pain, and then, briefly, into delirium. He died Labor Day weekend. The two summer holidays bookend his decline like a pair of brackets.

I was with him when he died. He was alone in bed when I arrived for the long weekend, his atrophied legs trailing behind him in the sheets like the tail of a grounded kite. His breath was desperate. I got into bed with him. I looked for recognition in his eyes, but there was none. Still, he seemed to understand that I was there. When I spoke to him and stroked his arm, his gasping calmed. Gradually it slowed. Finally, it stopped.

How many times do we revisit a single memory? How does that memory change over time?

When I started graduate school, I didn’t want to put Amy’s painting in my mom’s basement with the rest of the boxes. My painting is up the road a few miles from this house, at my aunt’s, where there is a wall big and empty enough to hang it. My aunt is very generous to take care of it for me, but I don’t think she really likes it. I think she sees it as a decoration that doesn’t quite match her living room. The painting still animates for me, though, when I visit. Even when I think I am done with it, that I have looked at it so much that I have gleaned all possible meaning from it, I end up returning.

I spoke with Amy on the phone the other day. I told her about my own new work, and also that I felt unsure about the direction it is going. She was sympathetic but unphased. “We want things to be connected to history that we understand. When the work shifts it can take you someplace new. It can freak you out,” she told me. She said that the way to move through that feeling was simply to keep working.

In the basement of this house, in a box where I store greeting cards and playbills and other memorabilia, is a letter my father wrote me in 1996. My school asked all the parents to send one, to be delivered during our junior retreat. It’s the only letter I have from him. His signature at the bottom and my name on the envelope are written in pen; the rest, a short half page, he typed in plain Helvetica font and printed out using our home computer, although he had beautiful handwriting.

I revisit this letter periodically, take it out of its box and reread it in the basement. The body of the letter is a summary of my life from his perspective, but it is just one paragraph. It is, essentially, a list of his memories of me: my first steps, my first swim meet, the way I sat still and watched the flames dance in the fireplace as a toddler. These were the fragments that solidified for him while the rest of time fell away.

When I first read it in 1996, I was in the backyard of a retreat house in rural Maryland. It was drizzling out. As I read, I rocked idly back and forth on a rusted swing. In the light rain, my name on the envelope and my father’s signature on the letter bled gently, like watercolor paint. Clouds of grey and violet bloomed on the white office paper. Letters smeared, exposing undertones of green in the black ink.

Those who make things, paintings and essays included, leave behind a trail of artifacts. Though maybe it’s best not to use the word trail. That implies a beginning and an end and accedes the rhetoric of progress, argues for the supremacy of the present. Maybe it’s best instead to think of the artifacts of our lives and our work as elements of a constellation around which we can draw, and then redraw, a form. Arrange, and also rearrange, a story.

When I hold my father’s letter today, one story seeps into another. The experience is ghostly, like the fog of memory. Like the passage of time.

__________________________________

Amy Pleasant’s exhibition Writing Pictures is on view at the whitespace gallery in Atlanta from September 15-October 28, 2017. Her work is also viewable at BaileyGallery.com and AmyPleasant.com.

Kerry Folan

Kerry Folan is a writer living on the Eastern Shore of Maryland and an assistant professor in the English department at George Mason University.