“The Page is So Flat, and ASL is So Not.” Sara Nović on the Limitations of Prose

In Conversation with Christopher Hermelin on So Many Damn Books

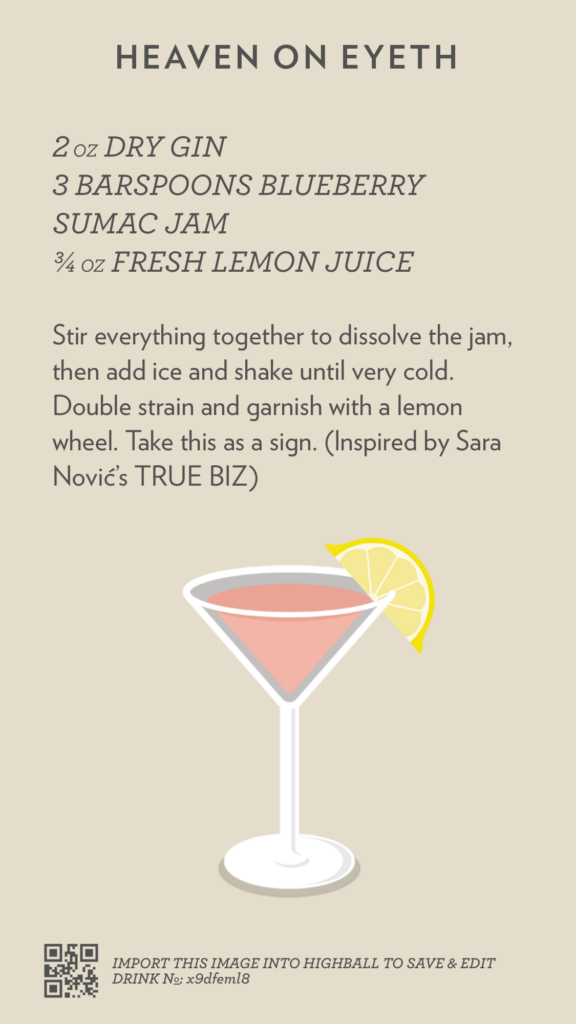

Sara Nović webcams into the Damn Library Zoom Zone to talk her new novel, True Biz. We discuss the limitations of prose in comparison to ASL, how she tried to mimic ASL on the page, some fantasies of Eyeth, and the propulsive nature of short chapters. Also a lot of other stuff. Plus, Sara brought along The Days of Afrekete by Asali Solomon, a book that both agree is “a feat of engineering” just like the NYT said.

Subscribe and download the episode, wherever you get your podcasts!

What’d you buy?

Christopher: Her Majesty’s Royal Coven by Juno Dawson, Booth by Karen Joy Fowler

Sara: a webcam

*

Also mentioned:

Girl at War by Sara Nović • The Heart is a Lonely Hunter by Carson McCullers • Deaf Republic: Poems by Ilya Kaminsky • Mrs Dalloway by Virginia Woolf • To the Lighthouse by Virginia Woolf • Parakeet by Marie Helene-Bertino • The work of W.G. Sebald • The work of Elena Ferrante • Little Fires Everywhere by Celeste Ng • Mad Men (AMC)

*

Recommendations:

Christopher: Bake a loaf of bread, buy nice spreads and jams for it

Sara: Blast Lil Nas X’s “Industry Baby,” make pasta

*

From the episode:

Christopher: One corner of deaf life that you illuminated is all the techniques for signing stories, like the subtle shoulder shifts to mean a different person, or the way you move your hands to mean different types of things. And I was curious if regular prose feels restrictive.

Sara: Yes, yes. And particularly for this book, because I wanted to be able to, in some way, represent ASL on the page. And the page is so flat, and ASL is so not, so that was something that I struggled with a lot in the early part of the book—trying to decide how do I show ASL on paper? How do I also differentiate between ASL and English? Because I was thinking originally, one of the first things that’s a very obvious difference between ASL and English is the syntax; it’s basically backwards. So I was like, ok, maybe I can just write it in ASL syntax. But then I thought, for a hearing reader, that’s just going to look like “broken English.” And that’s not showing them the point, which is that it’s actually better than English, particularly for these characters.

So the way the dialogue ended up in the book is basically spatial dialogue tags. People speak from different places on the page, and that’s kind of where they’re set up, which mirrors the way that if I was telling you a story in ASL, I could set people up around me like that. And then if I just point back over there, you remember who I was talking about. So they have places from which they speak in a given chapter. And because it visually sets the dialogue far apart from each other rather than just a new line when you speak in English, I hope that it illustrates that ASL for the deaf characters, and even for February, is a much clearer way of communicating. And obviously, it’s a visual separation as well.

Christopher: It was very effective, and it was also exciting to see this mixed in with not just regular prose and dialogue tags, but also with text messages and technology. Because your last novel was sort of a period piece. I don’t know if you would necessarily think of that for something that’s partially set in the early 2000s and the 90s. But it is—that was 30 and 20 years ago. But True Biz is very much set in the now. And it was another thing that I had just never thought about, that Charlie is being introduced to all of these phone apps and these things that she’d never had access to before. I wanted to know about your relationship with technology, and also what technology means for story for you.

Sara: I think technology makes fiction writing harder in a lot of ways. But for the deaf community, deaf people are historically really early adopters of technology because we’re not located in one specific place the way that another cultural or ethnic group might be. So we’ve always needed to figure out ways to communicate with one another even before the internet. For example, in the 60s, we were kind of ripping the guts out of—I don’t even know what you call this, I guess it’s sort of a telegram. The Western Union machines, people were going to the dump and ripping the guts out of that and attaching it to a typewriter and a phone line. So basically, you can text each other before texting existed.

So, that has always been a part of deaf culture, and also a big part today of how we communicate with the hearing world, too. For me, if I’m going to go into a store and everyone has a mask on, then I’m just going to type something on my phone and we’re all going to move on with our lives. The fact that Charlie has never met another deaf person before, it never really occurred to her because she had always been taught basically the burden of communication is on you, and you have to do it this very specific way or you’re doing it wrong. And so, that’s one of the things that River Valley opens up for her.

*

So Many Damn Books

A blessing, a curse, a podcast. est. 2014. Christopher (@cdhermelin) invites folks to the Damn Library to talk about reading, literature, publishing, and trying to make it through their never-dwindling stack of things to read. All with a themed drink in hand. Recorded at the Damn Library in Brooklyn, NY.