The Overwhelming Power of Beauty: Deconstructing Edith Hamilton’s Mythology for Modern Times

Kathryn Lofton on Greek and Roman Classics, Scholarship, and Religion

Growing up, my family had a patron: an artist who gave us his used Dodge Dart when my mom’s job took her off a bus line and who sometimes handed me five-dollar bills at the end of his visits to our house. He was a deeply kind person who saw in our Erskine Caldwell clan something worth salvaging from the fate otherwise predicted by demographics.

When I was ten, he handed me a paperback copy of Edith Hamilton’s Mythology: Timeless Tales of Gods and Heroes (1942) and said, “All educated people know mythology.” I took the book and ran upstairs, where I immediately wrote my name and the date in ballpoint pen on the inside cover, as if the ink was an incantatory potion that would launch me to the ranks of the educated.

The scene sticks with me, I think, because so many of my earliest memories involve women teaching me to read and men assigning me things to read. As with most US children who attend public schools, the majority of my instructors were female. As with most US children, my mother was more involved in my educational development than my father. Social scientists work to get dads more involved because research indicates that fathers’ involvement in their child’s early education is correlated not only with academic success but also with improved overall well-being.

Somehow, the absent figure is the most affecting, a myth unto himself. In the weeks, months, and years after the slender book became mine, I read and reread the stories of love and adventure that Hamilton rendered so wryly: Cupid and Psyche, Pyramus and Thisbe, Orpheus and Eurydice, Pygmalion and Galatea. The stories had no Disney endings. They concluded with limited lover visitation or a harassed gal being turned into a linden tree.

I also drank in the Steele Savage illustrations (a 1970 reviewer in The Classical Outlook: “The illustrations are strikingly beautiful, although they bear a closer relationship to Fantasia than to anything Greek”). Was it weird to wish I could turn into a forever-bubbling spring (like Arethusa) or a shining-leaved tree (like Daphne)? I liked how overpowering emotions guided every mythological action and reaction: cockeyed desires strung together risk and longing, manipulation and capture. Part of the thrill was not knowing what role I wanted for myself in the story.

“He decided that he could never rest satisfied unless he proved to himself beyond all doubt that she loved him along and would not yield to any other lover.” That’s Hamilton writing about Cephalus, but the line fits at least seven other characters. I wanted to be the one who stirred that desire, that impulse to possess. Or did I want to be the one who felt it?

The key plot point in these stories seemed to be pursuit. But it was pursuit inside a cloud unknowing, a shroud of darkness. A god chased you; someone accidentally stabbed you; you couldn’t help returning to a spot where a first tryst occurred; you were visited for nighttime pleasure by someone you couldn’t see. All of this stalking and constraint and strength of feeling made me feel a little woozy as I read in my bunk bed. I couldn’t name what that wooziness was. I could only see myself wanting to recreate its conditions, over and over.

Much later, I’d focus my educated self on getting down and geeky on all of this. I’d learn about the role of women in Greek and Roman antiquity; how ancient Greeks and Romans perceived rape and how Athenian law adjudicated rape accusations; why Greeks liked to talk about love coming through arrows; how to conceive of consent in classical Athens; and how to teach rape scenes from Ovid’s Metamorphoses in the era of trigger warnings.

I would join a field—the study of religion—in which explaining the local mindset of seemingly awful things is standard practice. For example, one of the field’s leading lights once explained (and later, upon reflection, modified) that the Greek goddess Persephone’s “proper name” is “only bestowed when she has been initiated, become an adult, and lost her maiden status.” What the original claim underlines is that the myth of Persephone should not be understood through modern ideas of rape. What we think about sexual violence today is unhelpful to understand the properly “cosmic event” recorded in the myth of Persephone.

Hamilton, too, comments that being so initiated gains its subject “geographical fame,” suggesting that Europa cut a deal for a spot in the atlas. “Nothing humanly beautiful is really terrifying,” she writes, setting a stage for readers like me to think that when Zeus transformed himself into a bull and “lay down before her feet and seemed to show her his broad back,” we should see the overwhelming power of beauty—not the overpowering power of power.

Religion, like myth, is not absolutely sequestered from scholarship.

Hamilton isn’t worried about power because she doesn’t see Greek mythology as an articulation of a religious system that ordered real people’s lives: “Greek mythology is largely made up of stories about gods and goddesses, but it must not be read as a kind of Greek Bible,” she writes. “According to the most modern idea, a real myth has nothing to do with religion.” These were stories, not manuals for right living. “For the most part the immortal gods were of little use to human beings and often they were quite the reverse of useful.”

The professional person I have become is tempted to get lost in the debate about whether Hamilton has the distinction between myth and religion right. Perhaps this distinction is a practice of myth making. Stories can and do serve as manuals; religion, like myth, is not absolutely sequestered from scholarship.

Still, I can’t stop thinking about how I got here. Thinking about all the men who handed me myths hoping to make me their educated equal, about the person I was, gobbling up every scrap they gave me. I remember how it felt so good, so sexy, when I could identify the figures in that Rubens painting or when I knew the W. B. Yeats allusion to Leda without looking it up.

Hamilton made the route to being clever very easy. It’s hard to tell how much pleasure she extracted in her own life from this work. She was the kind of person who, according to her closest student, friend, biographer, and life partner, Doris Fielding Reid, “liked men better than women.”

By her own description, she was a schoolmarm who taught generations of students at Bryn Mawr School, developing its rigorous classical curriculum and fundraising for disadvantaged daughters to gain access to elite education. Yet her legacy includes focusing on how to close your eyes and slide onto Mount Olympus via the back of a bull.

It was only long after I was handed Mythology that I would wonder if being understood as properly educated required the eminently useful myth that rape could be a cosmic event. It was still much later when I wondered: maybe it was an initiatory rite I needed to undergo in order to get my name into the atlas?

“The fact that the lover was a god and could not be resisted was, as many stories show, not accepted as an excuse,” Hamilton explained in her version of Creüsa and Ion. “A girl ran every risk of being killed if she confessed.”

These are stories, we are told. I like to think she told them to us not to bring us to woozy oblivion. I like to think she hoped we might use our educated power to draw new maps.

__________________________________

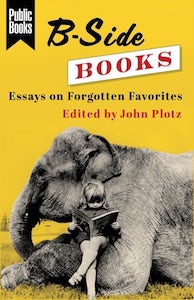

Excerpted from B-Side Books: Essays on Forgotten Favorites. Used by arrangement with the publisher, Columbia University Press. Copyright © 2021 by Columbia University Press. All rights reserved.

Kathryn Lofton

Kathryn Lofton is a historian of religion who teaches at Yale University. She is the author of Oprah: The Gospel of an Icon and Consuming Religion.