The Origin Story of an Iconic Adaptation: The Graduate

On the Life and Times of Wunderkind Novelist Charles Webb

Dustin Hoffman, upon reading Charles Webb’s first novel, came away convinced that its hero was a sun-kissed California preppy: tall, blond, and good-looking. He was certain that somewhere in the pages of The Graduate he had found precisely this description. That’s why he told director Mike Nichols that the role of Benjamin Braddock was not one he felt equipped to play.

Hoffman, it turns out, was quite wrong, in more ways than one. Author Charles Webb never provides the slightest physical description of Benjamin Braddock. In Webb’s spare, stripped-down novel, we come to know Ben—as he beds a middle-aged matron and then runs off with her beautiful daughter—solely through his words and deeds. But the WASP traits that Hoffman, and so many others, have projected onto the character offer a near-portrait of the artist as a young man. Charles Webb was to prove, however, far more complicated than his bland surface might imply. I’d call him a rampant idealist, one who has resisted for more than fifty years the pragmatic demands of adult life.

Born in San Francisco in 1939, Webb was raised in Southern California’s old-money Pasadena, where his father was a socially prominent heart specialist. Young Charles attended Midland School, a small Santa Barbara–area boarding school that taught self-reliance and independent thinking, then was accepted into the class of 1961 at venerable Williams College in Williamstown, Massachusetts. Dating back to 1793, Williams has been hailed as one of America’s top liberal arts institutions. Though in Webb’s day the student body was exclusively male (female students were admitted beginning in 1970), the young man didn’t lack for female companionship. In his junior year he met Eve Rudd, a Bennington sophomore whose parents were on the faculty of a Connecticut prep school. The legend (one of many surrounding the pair) is that Charles and Eve’s first date took place in a local graveyard. In any case, both were totally smitten, and before long Eve was pregnant. They decided to marry, but soon changed their minds. That’s when Eve’s parents whisked her off for an abortion, then enrolled their errant daughter in a Baptist college out West, the better to keep her from Webb’s embrace.

After graduation, a restless Webb returned to his home state. He audited a chemistry course through the University of California, Berkeley, toying with the idea of becoming a doctor like his father. In the Bay Area, he would eventually reunite with Eve, who’d come to San Francisco to study painting. But a postgraduate fellowship from Williams (akin to the Halpingham award won by Benjamin in his novel) allowed Webb to pursue his dream of a writing career. While pining for Eve, he’d been dabbling in short fiction. Then, newly home from college, he chanced upon a bridge game in his parents’ living room. One player, the alluring wife of one of his father’s medical colleagues, sparked his imagination. As Webb told an interviewer years later, “at the sight of her my fantasy life became super-charged.” Few words passed between them, and certainly there was nothing resembling a liaison, but off he went to the Pasadena Public Library and “wrote a short plot outline to get that person out of my system. My purpose in writing has always been to work things out of me.”

Webb’s writing fellowship helped him return to the East Coast, where in 1962 he melded his Mrs. Robinson fantasies with his romantic attachment to Eve in a short novel he called The Graduate. As he explained soon after the film version was released, “Anything I write is autobiographical. I don’t think it’s anything to feel funny about.” He consistently warned, however, that his supporting cast should not be confused with reality. (Such statements did not help improve the mood of Eve’s mother, Jo Rudd, who resented until her death the widespread assumption that the predatory Mrs. Robinson was created in her image.) Webb may have put himself into his hero, but Webb’s novel remains surprisingly vague about what’s eating this very privileged young man. This vagueness has turned out to be an unlikely advantage: In both book and film, the root source of Benjamin Braddock’s discontent remains so elusive that whole generations swear The Graduate reflects their personal tale of woe.

The Graduate was bought by an upstart publishing house called New American Library. (Its editorial director, a former film executive named David Brown, would eventually return to Hollywood and produce Jaws, among other monster hits. In 1962 his wife, Helen Gurley Brown, enjoyed a monster hit of her own, thanks to the publication of her Sex and the Single Girl.) What sold Charles Webb’s novel was doubtless the outrageous situations it portrayed, along with a distinctively austere prose style modeled after the work of Harold Pinter, whose plays Webb had discovered on a college-years trip to London. He was all of 24 when The Graduate appeared on bookstore shelves in October 1963. Though he insisted his work was a character study and not a generational attack, it angered his father, whose fury did not subside until the film version proved a major hit. This would not be the only time that father and son failed to see eye to eye. Webb would eventually turn down his inheritance, claiming to dislike the idea of family members at one another’s throats.

To those of us who savor the wit of the film, the design of The Graduate’s original book jacket looks surprisingly somber. Noted graphic artist Milton Glaser produced an image of boldly silhouetted faces, one on the left and two on the right, looking toward one another across a void. I’m assuming this is meant to signify Benjamin pitted against his parents, because the accompanying flap copy strongly underscores the novel’s generational tug-of-war: “The bewildering loss of communication between parents and their grown children—the one experienced, wise, and deeply committed to the values that have shaped their lives, the other questioning, skeptical, and disruptively honest—forms the basis for Charles Webb’s remarkably vivid and haunting book.”

But hey, what about Mrs. Robinson? It’s not until deep within a second paragraph that there’s even a hint of the novel’s famous romantic complications: “Ben’s probing questions to another generation unable to understand them, his disillusionment with a society seemingly incapable of explaining its most honored values, his strangely urgent affair with an older woman and its unexpected outcome, will produce in some a response of anger, in others a smile of understanding and sympathy.” Nowhere is there the slightest recognition that readers might find the story of The Graduate sexy and fun. Instead, the focus is entirely on Webb’s probing of intergenerational tension. On its front cover, in bold typeface, The Graduate is solemnly praised as “a novel of today’s youth, unlike any you have read.” All this hype is aimed, I suspect, at parents trying to understand their rebellious next of kin. New American Library’s marketing department seems not to have been looking for readership among the hordes of emerging adults trying to make sense of the world into which they were born.

Another feature of the book jacket is its prominent author photo, which takes up most of the back cover. Charles Webb, slim and blond, is depicted in conservative jacket and tie, with his hands in the pockets of a tweed topcoat. His hair is short and his expression soulful, as he modestly turns his head away from the camera’s gaze. This photo is credited to Eve Webb, to whom the novel is dedicated. The two were married in 1962, apparently with her parents’ blessings. The Webbs gifted the young couple with a six-month trip to Europe: Charles lugged along a typewriter on which he wrote daily while his bride went sightseeing alone. Not exactly a storybook honeymoon, but they must have spent some romantic time together, because Eve was once again pregnant when they returned to American shores. Despite Eve’s swelling belly, Charles convinced her to accept a housemistress position at a boarding school while he continued working on new novels and plays. He also persuaded Eve to sell their wedding gifts back to the givers, a move that must have baffled family friends who hardly wanted to purchase the same chafing dish twice. A few years later, Webb could not explain his motives, other than to say (to Los Angeles magazine’s John Riley) that he didn’t want the presents to own him. This eccentric rejection of material objects, even those given with a full heart, would point toward even more flamboyant gestures in the years ahead.

The Graduate, an experiment by New American Library in drumming up business for a fledgling hardcover line, got little attention from either the press or the reading public. But on October 30, 1963, the New York Times published a brief review by Orville Prescott. He praised the book’s bravura dialogue but called the novel “a fictional failure” because of its “preposterous climax” and the sidestepping of its hero’s psychological motivations. I’m convinced he hit the proverbial nail on the head when he asked, “Was Benjamin upset by sex? by the state of the world? by despair and the dark nights of the soul? by mental illness? Benjamin didn’t know. Mr. Webb doesn’t seem to know either.” Still, Prescott lauds the young author for having “created a character whose blunders and follies just might become as widely discussed as those of J.D. Salinger’s Holden Caulfield.”

In the long run, Prescott was quite right. His reference to the hero of Salinger’s The Catcher in the Rye piqued the interest of an ambitious young producer named Lawrence Turman. Salinger’s famous novel, a touchstone for restless adolescents of my generation, had been coveted by major filmmakers since it was published in 1951, but the reclusive novelist turned down even the most lucrative offers. If the movie rights to The Catcher in the Rye were unattainable by Hollywood’s finest, perhaps The Graduate would be a good substitute. Turman quickly bought and read Webb’s novel. His first thought was that Webb might make a good screenwriter. He soon changed his mind about that, telling me in the course of a frank 2015 interview that Webb “gave me in his book everything he had to give.” Later suggestions by Webb (buried in Turman’s archive at UCLA) as to how to adapt his novel for the screen convince me that the young novelist seems not to have understood his own literary strengths. For the Berkeley section of the script, Webb suggested that Ben’s desperate quest to win Elaine’s love be interrupted by cutaways to his anguished parents back home. At the same time he advised that Ben—posing as a jargon-spouting medical student in order to crash a party attended by his romantic rival—be embroiled in Marx Brothers–ish antics like hiding in closets to eavesdrop on a spat between Elaine and her college beau. Such an ungainly blending of melodrama and farce, violating the story’s tone just at the time when the audience expects a ratcheting up of tension, shows the wisdom of Turman’s hunch that Webb was not equipped to become a screenwriter anytime soon.

Though Turman had his doubts about Webb, he continued to be obsessed by the novel itself. As he wrote in his 2005 book, So You Want to Be a Producer, “The weird dialogue and situations were funny and nervous-making at the same time.” What especially stuck in his mind were two evocative word pictures: a young man in full SCUBA gear peering up from the depths of his parents’ swimming pool, and then the same young man, his clothing in disarray, seated in the back of a public bus next to a young woman in a formal wedding gown. Turman saw in these images his chance to move up to the Hollywood big-kids’ table.

__________________________________

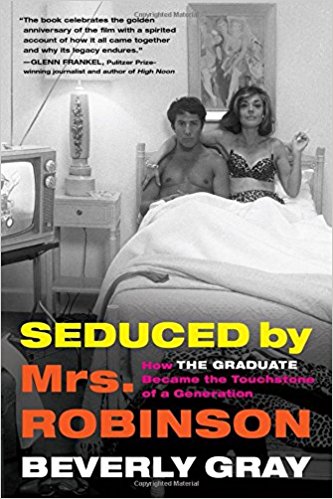

From Seduced by Mrs. Robinson, by Beverly Gray. Courtesy Algonquin Books, copyright 2017 Beverly Gray.

Beverly Gray

Beverly Gray is the author of Roger Corman: Blood-Sucking Vampires, Flesh-Eating Cockroaches, and Driller Killers, Ron Howard: From Mayberry to the Moon . . . and Beyond, and Seduced by Mrs. Robinson: How The Graduate Became the Touchstone of a Generation.