The Old Becomes the New: Lawrence Sutin on the Art of Transforming Books

“The freedom of erasure is its greatest allure.”

I am a book lover. I have been since I was old enough to hold them and turn their pages with my own hands. Books are precious to me as worthy guides and jolly friends. I have a basement full of all sorts of them.

So why have I become the sort of seemingly despicable person who regularly marks up old books with gel pens and Wite-Out so that the original text becomes largely unreadable? Why have I committed yet more heinous biblio-crimes? Sometimes I rip book bindings in half, strip their reusable cloth covers from their cardboard backings, and tear out the pages I want to cut up for collage or language material to be glued into the books I am marking up.

I am driven to these desecrations out of artistic passion. Having discovered the challenges and joys of creating new books out of old ones, I believe that—far from disrespecting books—I am celebrating both their surprising mutability and their enduring beauty. I cannot resist putting to use artistic materials from old books that would otherwise, in many cases, be headed for recycling bins.

Libraries regularly cull and discard titles that haven’t been checked out for years. I rescue books from those library purges, as well as from thrift stores and garage sales. No one else much wants them as they tend to be a humble lot—outdated textbooks and manuals, forgotten histories and analyses, footsore fustian poetry, romance novels from which the romance has dwindled away.

These books are often rife with racism, sexism, pomposity, and cheesy melodrama. They need to be altered. I find myself believing that I am restoring them to literary health. But I also, on occasion, erase books that I know to be masterpieces, such as Euripides’ Electra and Shakespeare’s The Tempest. And yet, from the standpoint of erasing and altering, I approach them no differently than I do wretchedly bad books. The essential challenge and joy remain the same. By choosing the language on each page that speaks to me without regard to the original author’s syntax or content, I can create startling text-and-image explorations of the human psyche and its fantastical pursuit of what it hopes is happiness.

I first discovered the power and beauty of altering books through erasure and collage when my friend, the poet and essayist Mary Ruefle, showed me one of her own works in this vein. I was transfixed. Mary’s aesthetic is distinctly her own. She does her erasure by whiting out rather than using colored inks.

The imagistic compression of her language stems from her great gifts as a poet. She collages vividly, but sparingly, in harmony with her newly created erasure verse. It was in homage to the inspiration that Mary provided me that her An Incarnation of the Now was the first book published by See Double Press (devoted to text and image explorations), founded by my wife Mab Nulty and myself.

As I explored my own voice in erasure, I gravitated toward the intricacies of sentence syntax as befitted my love of writing prose. I also found myself collaging more and more with every erasure project I undertook. In part, this was due to a gradual gaining of confidence in myself as a visual artist after seeing myself for so long as a writer alone.

In A Postcard Memoir, I had tried to convey the essence of my life through short vignettes accompanied by postcards that amplified the prose through unexpected and even exotic visual associations. But I found that choosing postcards was a far simpler matter than creating collages in which multiple image sources intermingle within the physical confines of a page with a newly erased text. My abiding inspiration for taking on this challenge is William Blake, a genius both as a painter and engraver and as a poet, whose illuminated works are, for me, the greatest examples ever created of what text and image in combination can achieve—the dance of dreaming wisdom.

What is most enjoyable to me about the erasure and collage process is the inevitable element of surprise. Writers have long sought ways to tap language creativity by lessening the dominance of conscious control. Surrealistic automatic writing and the cut-up method of William S. Burroughs are two relatively recent examples.

The erasure of old texts is an ideal way for a writer to surprise themselves. The key to the deepest surprises, I think, is to avoid any form of close paraphrase of the existing text while you are erasing. Instead, try to create an entirely new meaning for every page, one that you feel quite sure the original author never had in mind. One metaphor for this process that I enjoy is that of alchemy. As the erasure-alterer-alchemist, you transmute the dross of the original text into the gold of new beauty and meaning.

How to choose the right old book to place in your alchemical crucible? In my case, I am looking first and foremost for a book that can withstand the rigors of being transformed. Is the book too tattered or mildewed? Is the binding strong? Are the pages made of paper sufficiently thick to withstand being erased without the ink bleeding through? Trust me, it is disheartening to put days of work into a book that ultimately falls apart in your hands.

Having established the physical bona fides of the book, I move on to consider the language. I read a page or two to intuit whether or not the text engages me. Engagement in an erasure context can mean finding the language beautiful. But it can also mean finding it stilted and ridiculous. So long as a response is sparked in me, I’ve found a book I can likely work with. My third and final criterion for book choice is the presence or absence of illustrations for the original text.

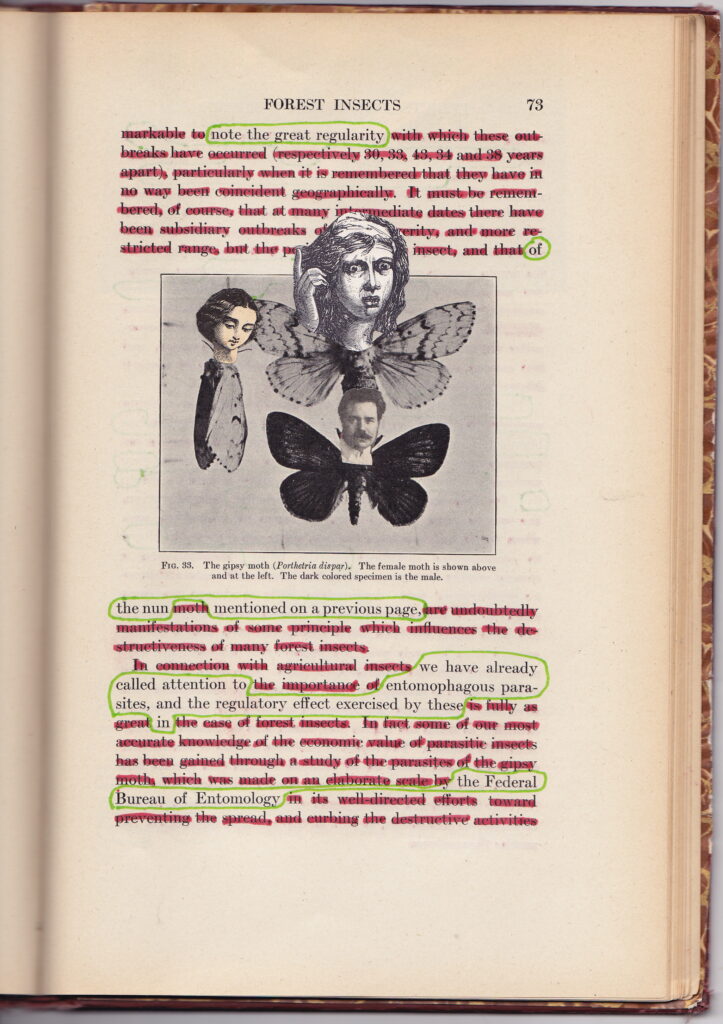

As I collage my erasure pages, I need to decide if I can successfully transform the existing illustrations into collaged-over elements of my own artistic vision. For example, I had great fun working with the photographs of insects in an outdated research work—heartlessly discarded by a university library—that I transformed into The Seeming Unreality of Entomology, from which excerpts are given here.

In this work, my creative goal was to transform the scholarly tone of the text into a surreal reimagining of relations between humans and insects. It was great fun to portray serious entomologists as “persons who expose themselves after nightfall.” I also relished reducing detailed research conclusions into comic simplicity, such as the mock-profound finding that “parasites in the water of small quiet ponds, puddles, rain barrels, etc. are crude.” As these examples show, my aim is to avoid paraphrasing the original text and instead create paradox and surprise. To heighten that sense of surprise, I bring in collage images from outside sources of any kind, so long as they add a startling new dimension.

If any of this sounds enticing to you, I suggest that you find an old book, clip some images that strike you as having collage potential, have some pens and markers and Wite-Out and a glue stick handy—and dive in. The good news about transforming books is that there are no rules whatsoever. No canon to consider or disregard. The freedom of erasure is its greatest allure.

*

Let’s start a bit smaller than tackling the transformation of an entire book, while building our skills and comfort with erasure and collage.

Find an old book—poetry or prose, as you prefer—that you have never read. Browse through it until a particular page happens to catch your attention. Scan and print that page on a blank sheet of paper (or type out the page if you have no scanner). Consider the language as raw units of energy that can dazzle or explode when manipulated with imagination and daring. Using ink or marker or liquid Wite-Out or tape or any other erasing medium you wish, create your new text. You are out to say something you have never said before and never knew you could say, so let your intuition and enthusiasm be your guides in deciding what to erase and what to preserve.

Then find a minimum of eight clippable images that seem to you to bring something new to your freshly created text. Try out different positions and combinations before gluing them. Find the beauty in the surprise you have created.

All images from The Seeming Unreality of Entomology by Lawrence Sutin.

__________________________________

Excerpted from The Rose Metal Press Field Guide to Graphic Literature: Artists and Writers on Creating Graphic Narratives, Poetry, Comics, and Literary Collage, edited by Kelcey Ervick and Tom Hart. Copyright © 2023. Available from Rose Metal Press.

Lawrence Sutin

Lawrence Sutin is an award-winning memoirist, biographer, novelist, and erasure artist. His books include The Seeming Unreality of Entomology (2016), When to Go Into the Water (2009), Divine Invasions: A Life of Philip K. Dick (2003), and A Postcard Memoir (2003). Before he retired, he was a professor in the Creative Writing and Liberal Studies Programs at Hamline University and taught in the low-residency program of the Vermont College of Fine Arts. In 2014, Sutin and his wife, Mab Nulty, created See Double Press, an independent press dedicated to innovative interfusing of text and image. Their goal is to publish beautiful, compelling, and challenging books that might not otherwise see the light of day.