The Novelist Who Works as a "Seasonal Associate" at Amazon

Heike Geissler's View From Inside the Warehouse

I read an essay by Claudia Friedrich Seidel, which begins with an admission: “Yes,” she writes, “I too buy my books from Amazon.com.”

Yes, I say, I too buy my books from Amazon. I buy the books there that I can’t get elsewhere. What I don’t buy from Amazon is books or other things I can get elsewhere, not even if they’re cheaper there or delivered more quickly.

A few days before, I held a far too vehement lecture at my mother’s kitchen table, preaching that one doesn’t necessarily have to buy things one wants from the cheapest source. I said there was no order and no law that you have to choose the cheapest offer. My mother looked at me as though checking whether I meant it seriously, first of all, and secondly whether I might have turned into a rich woman overnight, someone who could afford to say such things.

I think of a writer I know, a woman who tries on everything in the stores in town before buying anything, and then orders the clothes later at home from online retailers having nothing to do with the stores in town. She says: I’m not going to give the stores anything. She says it seriously and a little stubbornly. She might as well say: I’m not going to let them rip me off over the counter. And so she prefers to buy from places where there are no counters, and the counter where the customer is ripped off or lured in or simply contacted is the customer’s own desk or kitchen counter or notebook table; that is, if the customer’s not simply balancing their computer on their lap or holding their tablet in their hand.

In any case, my boyfriend has mail from Amazon. Two children carry the parcel around the apartment, not understanding, just as I don’t, why the parcel doesn’t get unpacked right away. My boyfriend rescues his parcel and eventually tells us what’s in there: pants. Our older son complains and wants something too, and the younger one keeps on lugging the parcel around; it’s almost as big as he is. Two pairs of pants, says my boyfriend, and each pair was 30 euros cheaper than in the store.

Each pair? I ask. Each pair, he says. Damn, I say.

Days later, I spy the parcel in the hallway again, its corners slightly dented, ready for returning. The pants were the wrong color, my boyfriend says. They weren’t dark blue, they were blue-black. I shrug, kind of glad he didn’t manage to save 60 euros that easily, but perhaps that’s not true either. Perhaps I don’t care either, and anyway we’re not talking about these two pairs of pants bought by my boyfriend, we’re talking, for example, about the bluffs and cheats that Hannes Hintermeier described in a rather old article in the Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung, using the example of a nonfiction author who preferred to remain anonymous. This author, I read, “hated Amazon, with the full force of his passion. He preached that we ought to stand up to the monopolist with all our might. Admittedly, whenever he wanted a book, he simply told his wife and she ordered it for him—from Amazon.”

*

You won’t be packaging dispatches that reach that nonfiction writer or me or anyone else. You’ll be receiving goods inward and entering them in the warehousing system, so that the products can then be ordered. And it will take a while before you get deployed in the book section, which incidentally is mainly reserved for women, like reading novels once was. When you come to enter the myriads of books into the system you might be glad of it, or you might not. We’ll see when the time comes.

I was always glad, at any rate, to stand beside the gigantic book boxes and enter the books in the system, I looked at the books and knew what kind of thing the Germans buy, so, for example, I knew the Germans like to buy the humorous health writer Eckart von Hirschhausen, because I had a hundred copies of Eckart von Hirschhausen’s face on my desk and put them in a yellow crate. And I found out there really are an incredible number of vampire novels, something I could have guessed beforehand but wouldn’t have thought possible.

I was glad of the books every day at Amazon, but one day I found myself with a book in my hands written by a man I know, formerly a good friend of mine. I got a shock; it was an absolutely unexpected encounter between him and me.

I was glad of the books every day at Amazon, but one day I found myself with a book in my hands written by a man I know, formerly a good friend of mine. I got a shock; it was an absolutely unexpected encounter between him and me. There in the dispatch hall, where I placed approximately 40 of his books in the crate for preordered products—meaning I knew what people would read and what they considered a good Christmas gift—it was as if I were the chambermaid and he were the guest. It was as if we were showing our true faces. At first I thought nothing, and after that I thought simpleminded things. I measured my life against his with the yardstick of, which I didn’t have, unlike him. The man is part of the world in which a person can feed a wife and child by working a job he enjoys. With his book in my hands, I didn’t want to think much and I didn’t think much. I thought: I bet he has time right now to think about his next work; it would have to be called a work, and he’d have to be called a successful writer.

You, though, are now waiting at the meeting place by the shelf full of boxes in the dispatch hall, clutching your box of work tools and really on the serious side of life. You’re waiting around in the consequences drawn from your financial situation and the opportunities on the so-called labor market. Cold air streams past you. You pull the fleece jacket you’re wearing under the safety vest up to your chin, put the hood over your head. One of the gates to the dock doesn’t close reliably. That’s how it will stay and by the time you’re pretty much broken down you’ll be told the company won’t bring in a heater for your sake. You’ll say you don’t want a heater. But then, by the time you’re really broken down, you won’t be able to explain calmly what exactly you asked for (for the gate to be repaired at long last). You’ll notice a trembling that hasn’t come about deep inside you just at that moment, but instead has been trembling away for a while and is spreading to your limbs. You’re still looking ahead to a time of misunderstandings.

You examine the growing crowd of colleagues waiting for the shift to start, and you spot your workmates Grit and Stefanie. The two of them are chatting about the previous day. You join them, stand next to them, and there’s something very old inside you, something that comes from me, which I hereby hand over to you so that you can deal with it, give it the full treatment and get it over and done with once and for all. You wish the two women would include you in their little circle. You want that very much for a few seconds. But Grit and Stefanie barely look at you and don’t move a muscle to make space for you. They tighten up, and we’ll come back later to what you wanted here for a moment, to this wanting to belong, we’ll come back to the way everyone here wants at their core to belong, which is mainly because no one has any time left to belong elsewhere.

For the time being, there’s nothing about you that interests Grit and Stefanie. The two of them have become a team overnight and Hans-Peter also has a new friend, whom he’s telling nearby about how he nearly had a severe accident on the autobahn just now. His new friend says yes and aha and oh boy and sounds involved and absent at the same time. You don’t say anything.

The managers are gradually gathering in the middle of the crowd. They’re marked by their clipboards and colored lanyards and by the fact that they have enough space to position their legs in a commanding manner. The employees’ conversations gradually fall silent and everyone turns to the bosses. You take a few steps back to get to the outer edge of this gathering—which reminds you of a flag ceremony except it’s not held along the angular lines painted on the floor of a gymnasium, but as a loosely woven circle three to five people deep. You step back as far as possible from the area where the bosses are standing.

A bell rings to start the shift and the shift manager Mirko takes half a step forward out of the line of managers. He stands with his legs wide and taps the side of his clipboard against his left palm.

Welcome to the late shift, he says. As you can see, the docks are empty, but it won’t stay that way for long, we’re approaching our peak week. We haven’t got all that many inbound goods today, it should be a quiet shift. We have to make sure we leave something for the early shift to do, but it should be fine. We’re expecting a few deliveries. He pauses briefly and then continues. Good news: Amazon Italy opened today. There were seven orders in the first five minutes—a good start, I’d say.

Good news: Amazon Italy opened today. There were seven orders in the first five minutes—a good start, I’d say.

He looks around. Any safety tips? he asks.

You adjust your first impression. This isn’t a variation on a flag ceremony, it’s more of an American motivational huddle, like before a basketball game, except that the staff aren’t athletic and glamorous, just standing around in a very wooden, un-American way.

Right, says the shift manager, then I’ve got a tip. Please park your cars parallel to each other. We have to make optimum use of the parking lot now. We’ve got a lot of new staff. And keep an eye on the footpaths. Pedestrians have right of way.

He nods and taps the clipboard against his hand again. Have a good shift.

Most people go to their workstations. Hans-Peter, Grit, Stefanie, and you wait for Norman. That parking lot’s chaos, says Hans-Peter, you can’t get here early enough to make it in time, and you should see how some people park, all over the place and five attempts at hitting the spot. He comes up close to you; you retreat slightly. He reaches into the chest pocket of his overalls and takes out a packet of tablets. He looks at you in such a way that you know he expects something of you, something to do with the tablets.

Did you steal them? you ask.

Hans-Peter reduces the distance between you and taps his forefinger against his lips. Tooth abscess, he says.

Oh, you say. Hans-Peter explains that his tooth actually needs operating on but he’s pushed the operation back now.

But aren’t you in pain? you ask.

Sure I am, Hans-Peter replies, or I wouldn’t need this stuff—he pats his pocket.

You’d be better off at home then, you say.

Well I can’t stay home, I can’t, I’ve got to be here now, Hans-Peter says.

But if you’re sick? you say.

You could talk that way forever and you will talk that way a few more times, and in a few days—once you’ve got sick and then recovered again and you’re told to work right next to the roller door that doesn’t shut properly so that a coworker of yours doesn’t have to work there—you’ll go to that workmate and say you’ve just been sick so you really want to work in a warm spot and not in a draft. He’ll shrug and you’ll realize he’s sick right there and then, his eyes are watering. You’ll put your hand on his forehead and feel how hot he is. You should go home, you’ll say. He’ll shrug again and say he wants to be taken on permanently, though. You’ll repeat that he ought to go home but he won’t be put off, and you’ll end up working in the draft—shivering, sweating, shivering.

_______________________________

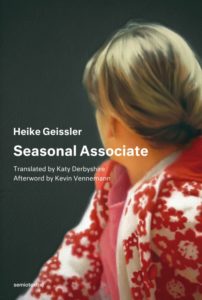

From Seasonal Associate by Heike Geissler. Translated by Katy Derbyshire. Used with permission of Semiotext(e). Copyright 2018 by Heike Geissler. Translation copyright 2018 by Katy Derbyshire.

Heike Geissler

Heike Geissler is a German writer based in Leipzig. Her novel Seasonal Associate is our now from Semiotext(e).