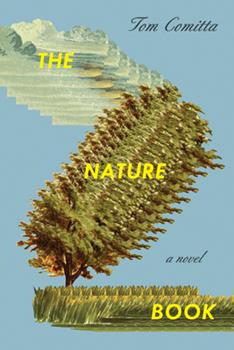

The below excerpt comes from Comitta’s novel, The Nature Book (Coffee House Press), a “literary supercut” of nature descriptions from 300 novels collaged into a single narrative—it contains no original writing by the author. To write this book, Comitta searched for “patterns in how authors behold, distort, and anthropomorphize nature and gathered them into a text that operates somewhere between narrative and archive, lyrical excess and data analysis.” As a story, the book moves through the rise and fall of seasons, extreme weather, and interspecies strife. It has everything we’re used to in novels—cliffhangers, plot twists, etc.—except for the human characters. This first chapter is a supercut of how authors think about time, the creation and destruction of the Earth, and summer.

*

Since the beginning, time was a form of sustenance, pleasant as the spring, comfortable as the summer, fruitful as autumn, dreadful as winter. Weeks, months, seasons passed with dream-like slowness, and the Earth moved in its diurnal course.

To a waiting horse, perhaps time passed with torturous languor. To a tree, this phenomenon was common enough; much more unusual was the fact that years passed, and by some accident another tree arrived, and flowers and birds and insects.

On earth time was marked by the sun and moon, by rotations that distinguished day from night. The present was a speck that kept blinking, brightening and diminishing, something neither alive nor dead. How long did it last? One second? Less? It was always in flux; in the time it took to consider it, it slipped away.

There were times, though, especially towards the end of a long, cold, dark winter, when time slowed to an operatic present, a pure present. Sun was all shrouded over with mist, and could no longer shine brightly, and the snow began to fall straight and steadily from a sky without wind, in a soft universal diffusion, a continuous symphony.

At such a moment it seemed that time stopped. The day and the scene harmonized in a chord. Words. Was it the shifting colors? The snow fell so thick that it was only by peering closely that such heavy flakes blended like the elements of color, elements that, somewhere in the grid of time, would recede and show that, amid the prostration of the larger animal species—the few nearby trees and plants buried under amorphous white cloaks and winter storms—time disappeared, and it was like seeing all time as you might see a stretch of Mountains.

All time. The slow passage of years! The constant alterations! It was all ephemeral, filmy, dreamy. It was the mystery of creation, the stupendous miracle of recreation; the vast rhythm of the seasons, measured, alternative, the sun and the stars keeping time as the eternal symphony of reproduction swung in its tremendous cadences like the colossal pendulum of an almighty machine—primordial energy flung out from the hand of the Lord God himself, immortal, calm, infinitely strong.

The earth was at work, as it is always at work, and it moved slowly. A thousand times in the future this irresistible movement would change the aspect of the earth’s surface. The mountains continued to push upward. New-forming land would rise from the sea to be weathered by storm and wind. Sometimes the sea would wash in bits of animal calcium, or a thundering storm would rip away a cliff face and throw its remnants over the shore. At other intervals, flowers would bloom—spectral substance vibrating in silent winds of accelerated Time . . .

Time-lapse of a million billion flowers opening their heads, of a million billion flowers bowing, closing their heads again, of a million billion new flowers opening instead, of a million billion buds becoming leaves then the leaves falling off and rotting into earth, of a million billion twigs splitting into a million billion brand new buds. The grass would be growing and dying back to nothingness in much the same fashion.

Wherever sun sunned and rain rained and snow snowed, wherever life sprouted and decayed, places were alike. Winter was long. Spring was a very flame of green. On certain spring days, there was a hint of summer in the air—in the shadows it was cool, but the sun was warm, which meant good times coming.

When the days were longer, when summer afternoons were spacious, laughter was on the earth. Primroses were broad, and full of pale abandon. The lush, dark green of hyacinths was a sea, with buds rising like pale corn. The rich odour of roses and the light summer wind stirred amidst the trees. Flowers, acre after acre, bloomed side by side, each bathed in the sun, each held in thewind’s sway, each deeply rooted in the rich, dark soil. Poppies, sunflowers, daffodils, dogwoods, tigerflowers waved in the sun, and days were bright with the colored balls of song as the birds tossed back and forth, small unspeckled birds. These were the realities of the external world.

But here, the summer before last, as time went on and each day it became hotter, the soil became dryer, and much of the earth lay dried and cracked while water which had accumulated during the rainy season remained in deeper ditches and craters. Flowers slumped and grasses bent. The ground bred all manner of insects, and the mosquitos in particular seemed everywhere. Day after day was hotter than the day before, day after day the west wind blew and began to be regarded in a different light.

At first nothing had been outwardly altered here, but while the summer had gradually advanced over the western fields, beyond the elms and lindens, a sluggish stream, fed from snows in the mountains two hundred miles to the north, vanished completely. The land dried up, and the cloudless sky, the haze of heat, rather betokened a continued drought. All day long, every day, the blazing midsummer sun beat down, and there was no escape behind the boughs, in the shade of hazel bushes. The sunlight, filtering through innumerable leaves, was still hot.

Then one day the wind picked up—some southern wind of passion swept over, bringing with it the tang of verbena, and soon the sky was painted with a small number of flat clouds that looked like sandbars. The wind had freshened, and it grew, and grew, till soon, the air was crystalline as it sometimes is when rain is coming. The temperature dropped, and late that afternoon there was more activity overhead, clouds forming and moving. The blue cloud-shadows chased themselves across the grass like swallows. Real animals came along, flying a yard or two at a time, and lighting. And then the light rain began to blow on the wind although the sky was not properly covered with cloud. A mist of silver radiance kissed the earth. Nature smiled once more.

Thereafter the summer passed with routine contentment. Routine contentment was: In the mornings the meadow larks rose singing into the sky. All day the curlews and killdeers and sandpipers chirped and sang in the creek bottoms. Often in the early evening the mockingbirds were singing. And the days were bright. Trees, rich and voluptuous, waved in the sun, roses were in bloom. The night was luminous with moonlight.

Every hour, every day, was a good one. If it was going to rain, enormous clouds glowed like archangels. If the sun were shining through a mist, its light and glamour spread in all directions. It seemed as if a lull was here, the one solid reality. There were young colts and meadows. There were little hollows of water that caught the light and looked like precious stones scattered over the landscape. There were other comforting things.

As the end of summer came near, the weather remained unusually calm, but two events, two things, saddened. One. The air was very still. Some days not a leaf stirred on the green apple-tree. Not a single closed flower of the morning-glories trembled on the vine-stalk. Two. The martins were now coming and going elsewhere. Other birds in the valley were flying homeward to the south. It was strange how everything had been so full of life and funny and in a way sad. It didn’t make sense.

It was during those same weeks of change, flux and reflux, that the sunsets had become almost unbearably beautiful. Watching the sky go from yellow to pink, watching flights of martins sweep low over the Hills, was very pleasant. One evening, on the last day of summer, tall trees sent their shadows across the grass. The sky, as often on those summer evenings, had become a pale purple colour. The few clouds glowed blue and red and mauve. By the time the sun was low on the horizon, the amphitheatre of round hills glowed with sunset, the meadows golden, the woods dark and yet luminous, tree-tops folded over tree-tops, distinct in the distance. And soon the edge of the earth trembled in a darkish haze. Upon it lay the sun, going down like a ship in a burning sea, turning the western sky to flaming copper and gold. Wisps of cloud hung low like smoke rising from the trees. Other clouds, under an altered dispensation, were purely ornamental.

While the sun dipped lower and lower, the trees were silent, drawing together to sleep. An occasional yellow sunbeam would slant through the leaves and cling passionately to the orange clusters of mountain-ash berries. Only a few pink orchids stood palely by, looking wistfully out at the ranks of red-purple bugle, whose last flowers, glowing from the top of the bronze column, yearned darkly for the sun.

Just before the coming of complete night, the sky overhead throbbed and pulsed with light. The glow sank quickly off the field; the earth and the hedges smoked dusk. The sun had gone down, but the sky was still blue, a very pale blue, with a few high clouds still golden with sunlight. Soon four stars were visible in the place where the sun used to be.

As it grew dark, there was something . . . about the river and the good meadow land and the timber, about the clouds grinding against the mountains and the trees sticking out of the ground . . . something. Something to do with watching the sun set, watching the night build itself, dome-like, from horizon to zenith. Something special in the wind, the crickets and the birds, the stars swimming in schools through the night sky. Something special at the end of summer, a grand finale . . .

*

Sources in order of appearance:

Lonesome Dove, Larry McMurtry

The Lowland, Jhumpa Lahiri

Gulliver’s Travels, Jonathan Swift

David Copperfield, Charles Dickens

Lady Chatterley’s Lover, D. H. Lawrence

The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy, Douglas Adams

So Far from God, Ana Castillo

A Sicilian Romance, Ann Radcliffe

Molloy, Samuel Beckett

Rendezvous with Rama, Arthur C. Clarke

Hawaii, James Michener

A Tree Grows in Brooklyn, Betty Smith

The Flamethrowers, Rachel Kushner

Wives and Daughters, Elizabeth Gaskell

Ethan Fromm, Edith Wharton

The Prairie, James Fenimore Cooper

The Round House, Louise Erdrich

A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man, James Joyce

The Precipice, Elia W. Peattie

The Jungle, Upton Sinclair

Dracula, Bram Stoker

Shark Dialogues, Kiana Davenport

The Return of the Native, Thomas Hardy

The Octopus, Frank Norris

The Shining, Stephen King

A Tale for the Time Being, Ruth Ozeki

Slaughterhouse Five, Kurt Vonnegut

Centennial, James Michener

Housekeeping, Marilynne Robinson

Naked Lunch, William Burroughs

Autumn, Ali Smith

Not Without Laughter, Langston Hughes

The Professor’s House, Willa Cather

Song of the Lark, Willa Cather

Sons and Lovers, D. H. Lawrence

Gravity’s Rainbow, Thomas Pynchon

To Kill a Mockingbird, Harper Lee

Middlemarch, George Eliot

Yonnondio, Tillie Olson

The Picture of Dorian Gray, Oscar Wilde

The Adventures of Mao on the Long March, Frederic Tuten

Moby-Dick, Herman Melville

A Fall of Moondust, Arthur C. Clarke

The Catcher in the Rye, J. D. Salinger

Oryx and Crake, Margaret Atwood

The Homesteader, Oscar Micheaux

A Pale View of Hills, Kazuo Ishiguro

Zone One, Colson Whitehead

Little House on the Prairie, Laura Ingalls Wilder

Riders of the Purple Sage, Zane Grey

The Conquest, Oscar Micheaux

Main Street, Sinclair Lewis

The Monk, Matthew Lewis

2001: A Space Odyssey, Arthur C. Clarke

East of Eden, John Steinbeck

Desert of Wheat, Zane Grey

1984, George Orwell

Sea of Poppies, Amatov Ghosh

The Crystal Cave, Mary Stewart

Life of Pi, Yann Martel

And Then There Were None, Agatha Christie

Death Comes for the Archbishop, Willa Cather

Through the Arc of the Rain Forest, Karen Tei Yamashita

The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, Mark Twain

St. Irvyne, Percy Bysshe Shelley

Tarzan of the Apes, Edgar Rice Burroughes

The Island, Aldous Huxley

The Sea, The Sea, Iris Murdoch

The Book of Khalid, Ameen Rihani

Ceremony, Leslie Marmon Silko

The Virginian, Owen Wister

Ice, Ana Kavan

House Made of Dawn, N. Scott Momaday

Heat and Dust, Ruth Prawer Jhabvala

The Bird in the Tree, Elizabeth Goudge

Jaws, Peter Benchley

Watership Down, Richard Adams

Blood Meridian, Cormac McCarthy

Plainsong, Kent Harunf

Bless Me Ultima, Rudolfo Anaya

Remains of the Day, Kazuo Ishiguro

Tess of the D’Urbervilles, Thomas Hardy

White Noise, Don DeLillo

Go Tell It on the Mountain, James Baldwin

Remainder, Tom McCarthy

Gods Without Men, Hari Kunzru

The Awakening, Kate Chopin

The Namesake, Jhumpa Lahiri

The White Peacock, D. H. Lawrence

On the Road, Jack Kerouac

Loon Lake, E. L. Doctorow

Beloved, Toni Morrison

My Ántonia, Willa Cather

Sometimes a Great Notion, Ken Kesey

Clan of the Cave Bear, Jean M. Auel

State of Wonder, Ann Patchett

__________________________________

From The Nature Book by Tom Comitta. Used with permission of the publisher, Coffee House Press. Copyright © 2023 by Tom Comitta.