The Mysterious Man Who Discovered Neurons and Changed Science Forever

Benjamin Ehrlich on Studying the Genius Santiago Ramón y Cajal

Twelve years ago, I saw an image of a brain cell drawn by a man whom I had never heard of, Santiago Ramón y Cajal, and had what I recognize now was an awakening. At the time, I was so depressed that I had entered anhedonia, that vast terrain of feelinglessness. My only activity was to help my friend shoot music videos for a shady entrepreneur trying to launch his preteen son’s band into pop stardom.

One day, my friend and I argued about whether it was possible to combine science and art or whether they would always be separate domains. My friend, who studied neuroscience and was a filmmaker, maintained that the two could be united, while I, who studied comparative literature and aspired to write, was skeptical of science.

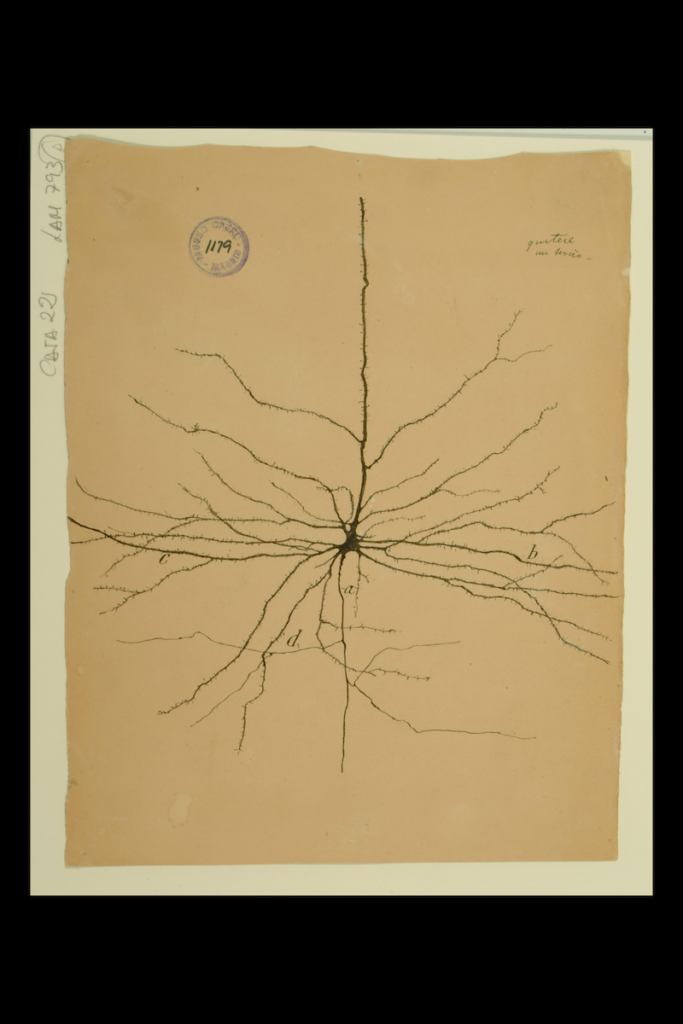

That night, as an olive branch, my friend sent me an email with nothing but a link to a Wikipedia page of Cajal, who it said won the 1906 Nobel Prize for discovering neurons, which he called “butterflies of the soul.” I felt a sense of the poetic. But, I knew nothing about the brain except that I had one, and it was causing me to suffer. A psychiatrist once sketched a neuron for me on a cocktail napkin he took from his pocket to explain the mechanism behind SSRIs. It looked shameful and pathetic—a hapless, distended bulge. In Cajal’s view, the inside of my head was beautiful: small, black dots radiating slender, thread-like appendages, at once otherworldly and familiar.

Here were the secrets behind our humanity, laid bare. Sensations crackled in my shoulder, like fireworks on mute, or the colorful spots you see when you rub your eyes, if those spots had a feeling, which traveled inward, as though following a fuse, until they reached my heart and I started to sob.

Of all the organs in the human body, the brain is the most ill-treated and misunderstood. The ancient Egyptians, who enshrined livers and lungs for use in the afterlife, churned the brain with a hooked rod jammed through a cadaver’s nostrils, then spilled the gruesome stew onto the scorching desert floor. According to Aristotle, the brain served as a refrigerator to the heart, cooling blood during circulation. Galen, the Greek physician whose theories dominated Western medicine for over a millennium, proposed that the brain was made of sperm. In the latter half of the 19th century, scientists clung to another misunderstanding: that the brain was composed of a single, labyrinthine thread, immutable and impossible to disentangle, known as a reticulum.

Armed with a rickety light microscope, a barber’s razor, and a trove of inexpensive chemicals, Cajal, an unknown researcher from the scientific backwater of Spain, demonstrated that, inside that gray, wrinkled lump of our brain, there are countless individual cells—later termed neurons—which must communicate across infinitesimal gaps—later termed synapses. In the same way that all Russian literature came from Gogol’s “Overcoat,” as attributed to Dostoevsky, and all modern American literature comes from “Huckleberry Finn,” as Hemingway said, we owe our modern view of the brain to Cajal.

There was nothing else to do but to know the man responsible for that drawing. Cajal’s autobiography, Recollections of My Life, had been translated into English. The prose style, that of a country boy desperate to sound urbane, was so transparent it was charming. His life story seemed almost fictional. The future Nobel laureate was born in a tiny village atop a mountain in the remote Pyrenean region of northern Spain where the illiteracy rate was around ninety percent.

Throughout his childhood, his father, a trained barber-surgeon, traumatized him with medieval punishments. Cajal, whose disobedient streak, according to his own legend, traced back to infancy, refused to behave. The book reads like a picaresque novel, and that was his intent, since he fell in love with the genre at an early age and dreamed of himself as a protagonist. This literary fanaticism is what first drew me to Cajal, who seemed to read books like I did: not at a remove but rather internalizing them, following their guidance, with no separation between the world of the book and reality.

“I have a brain enslaved to the heart,” he said.

In Cajal’s time, the most advanced technique for visualizing cells was histology, an intricate, temperamental method of treating dissected tissue with chemicals so that their precipitates clung to hidden structures, which, under a light microscope, became miraculously visible, often in spectacular color. The process is prone to error; the slightest change in the temperature of the laboratory or the chemicals, the volume of the chemicals, the timing of their mixtures, and the duration of immersion are among the factors that can skew results. For most researchers, they were impossible to replicate.

The problem is one of seeing; artifacts, foreign matter such as grease, hair, air bubbles, traces of cotton, hemp, silk, or wool, could deceive the uninitiated, the fatigued, or the biased. Cajal, who, when he was young, could not help but merge fiction and reality, became among the most reliable sources of fact in the history of science, as neuroscientists, over a century later, still cite his work hundreds of times each year. Unlike his contemporaries, who lived in great cities and compared the brain to a telegraph, Cajal drew on his childhood in the pre-industrial Spanish countryside in order to clearly see individual forms, which seemed to him naturalistic.

Cajal’s scientific masterpiece, Histology of the Nervous System of Man and Vertebrates, while not a novel, play, or poem like the “great books” I had read in college, struck me nonetheless as a literary masterpiece, its prose gleaming, scalpel-like, with precision and detail, a triumph of logic and clarity. Almost like the Book of Genesis, Cajal sweeps through a great creation story, of the evolution of the nervous system from unicellular organisms to human beings. Advice for a Young Investigator, a manual of scientific research, read to me like a counterpoint to Rilke’s Letters to a Young Poet. Before we discover the brain, Cajal said, we must discover ourselves. Practice alone is one’s teacher.

Students would flock to him with questions and complaints; “Just persevere,” he would say. In rational pursuits, he prized passion as much as intellect; “I have a brain enslaved to the heart,” he said. Like Renaissance masters, he taught by doing, and his example changed the lives of many of his students, who revered him. “Every man, if he is so determined,” Cajal said, “can become the sculptor of his own brain.” I, with my suffering brain, believed him.

Every year, I expected to see a biography of Cajal, but one never appeared. Finally, despite my lack of publications, my never having taken a science course, and my only high-school level knowledge of Spanish, I decided that the responsibility had fallen to me. I left my job and apartment and bought a ticket to Spain, where Cajal is a folk hero, one of the most famous countrymen in history, with a street named after him in every city and a statue in Madrid’s Retiro Park. It was my own Camino de Santiago—the 21st century author’s version of a medieval pilgrim’s way.

I visited every place where Cajal had lived and worked, from his birthplace; to the highland towns of his youth; to the provincial capital of Zaragoza, where he studied and worked in his twenties; to Valencia, where he held his first Chair of Anatomy; to Barcelona, the city that he may have loved most; and finally, to the royal capital of Madrid, where he died. There, I accessed the archives at the Cajal Institute, a nondescript room next to a regular working laboratory, where I came face-to-face with the drawing that, like Rilke’s “Archaic Torso of Apollo,” had forced me to change my life.

It is eerie to remember that we share our world with the dead. The past overlays the present and we struggle to resolve the two, like double vision. “Genius” is a knotted word, igniting arguments about who qualifies—almost always a white man. We expect our geniuses to represent our society, even our civilization. To this end, Cajal’s resume is undeniable; historians rank him among the greatest scientists of all time, along with Copernicus, Galileo, Darwin, and Einstein. But in ancient Rome, “genius” meant something more intimate: an attendant spirit of a person or place.

It turns out that Cajal’s drawings are not copies of neurons but rather composites of observations of many neurons synthesized into a representative image, like a portrait. “Literary criticism should arise out of a debt of love,” writes the critic George Steiner. My biography of Cajal, The Brain in Search of Itself, arose out of a debt of gratitude. In a strange way, I owed him my life. I knew that there must be other curious and sensitive readers out there, and my hope is to transmit “the little sob of the spine,” as Vladimir Nabokov called it, to them too.

__________________________________

The Brain in Search of Itself: Santiago Ramón Y Cajal and the Story of the Neuron by Benjamin Ehrlich is available via Farrar, Straus & Giroux.

Benjamin Ehrlich

Benjamin Ehrlich is the author of The Dreams of Santiago Ramón y Cajal, the first translation of Cajal’s dream journals into English. His work has appeared in The Gettysburg Review, The Paris Review Daily, Nautilus, and New England Review, where he serves as a senior reader.