The Most Impossible Art: Anime, Literature, and the New Aesthetic Imagination

Lio Min Explores Gender and Sexuality with the Boundary-Pushing Possibilities of Anime

One of the hardest times I’ve ever cried during a movie was when I first watched Makoto Shinkai’s 5 Centimeters per Second. My laptop screen wasn’t big enough or its speakers deft enough for me to fully appreciate the film’s sensual environs, all shuddering flowering branches and whistling susurrus of swirling wind. But as a plaintive ballad played in the moment that two characters almost meet again for the first time in years, whatever combination of image and sound my machine could emit was enough to spring an emotional trap door under my body, and I welcomed the fall.

When the film was originally released in 2007, the only people I knew who’d seen it were my fellows on an anime graphic design forum. Nine years later, my first watch was still tapping into a cult cultural vein. “Manga” (generally, Japanese comics) and “anime” (generally, the animated adaptations of those comics) remained catch-all terms for girls with Manic Panic hair and dilated saucer eyes, or Doritos-shaped men yelling while they pummeled each other with fists and/or various elemental powers, or whatever you might’ve remembered from Cartoon Network’s Toonami. In the Western imagination, “anime” was a shorthand for all Japanese animation, in the same way that people use “YA fiction” or “beach read” to compress wildly disparate titles into a stylized genre.

Anime is ascendant in the culture, if not the ascendant art form of our era.

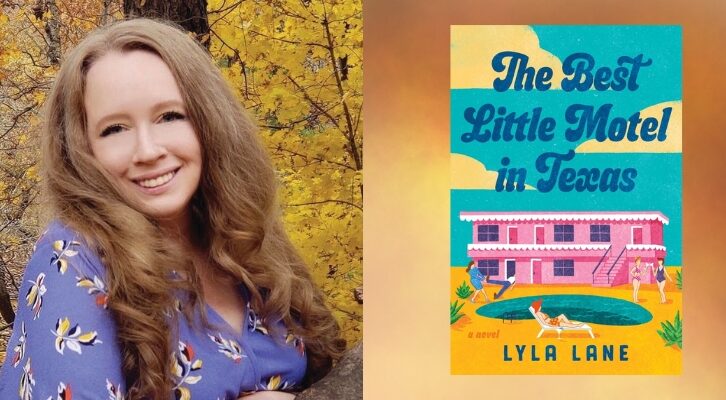

I’ll use this iteration of “anime” to make one claim: anime is ascendant in the culture, if not the ascendant art form of our era. I admittedly say this as someone who is growing their literary art in the garden of anime’s influence. But when I pitch my debut novel, Beating Heart Baby, to librarians and teachers, one of the things that catches their attention is the fact that anime is a pivotal component of both its inspiration and its content. Amongst Gen Z and the generations after them, anime is as much a fabric of their cultural consumption as “Netflix originals” are to millennials.

The most obvious reason for anime’s growing popularity is that in a super-saturated information culture where a clear and obvious distinction between “real” and “fake” no longer exists, anime is impossible. To be clear, all animation is impossible: it is an artistic medium in which nothing real must exist, though it requires considerable manpower and hardware to create. But while Western animation has its own dominant aesthetic (e.g. the Disney/Pixar style, where character and infrastructure designs are systematically rounded, as though a potter is constantly throwing them on their wheel), anime has a unique sensory language of its own.

Perhaps the most salient example of anime’s Japanese origins is the use of the natural world to supplement emotional moments, an impact of the country’s broad Shinto religious influences. Every anime fan knows these seasonal sensory signals: cherry blossoms for spring, cicadas buzzing incessantly and tanabata ribbons for summer, red maple leaves for autumn, snow and distant dog howls for winter.

Perhaps the most salient example of anime’s Japanese origins is the use of the natural world to supplement emotional moments, an impact of the country’s broad Shinto religious influences.

Almost a decade after he released 5 Centimeters per Second, Shinkai released his 2016 hit Your Name, which pulled directly from Shinto traditions and expressed his now-signature celestial imagery. He’s poised to become the anime director most likely to inherit Hayao Miyazaki’s and Studio Ghibli’s overseas clout because his films are suffused with gorgeous slice of life “moments”: in the same way people on the internet salivate over the food in Ghibli films, viewers now also obsess over the details of rain hitting pavement or light passing through train windows or shimmering objects streaking through Shinkai’s dip-dyed skies.

Anime’s hyperstylization paradoxically augments its underpinning human spirit. When I began to build the framework for Beating Heart Baby, I immediately turned to anime as my font of inspiration, focusing on a hyper-emotionality that blends and builds with the character and their environments. And as I fleshed out my characters, I realized that I had to include an aspect of anime particularly personal to me: an exploration of gender and sexuality as something more fluid, a baseline aesthetic malleability that places gender ambiguity in a more neutral space than “representation.”

To be clear, East Asian culture is still largely patriarchal and heteronormative, and anime very much mirrors that. Most of the time when characters’ genders are mislabeled or misread, it’s in the service of comedy, whether lightly off-putting or deeply offensive. And yet the medium flourishes with gender ambiguous characters like Haku in Naruto, the gems in Land of the Lustrous, Crona in Soul Eater, and Ed from Cowboy Bebop, who inhabit their respective series as features rather than bugs, illuminating the viewer’s self-conceptions of gender legibility and perhaps desire without forcing moral judgment or obvious self-identification.

Think of those Sailor Moon proportions—“even” cisgendered characters’ bodies can be exaggerated or obscured beyond the draggiest IRL transformations. Gender elisions are often part of some fantastic story mechanic, as in the series Ranma ½, and that greater allowance for gender play has led some right-wingers to blame anime for triggering MTF transitioning. But transition is increasingly becoming a character detail or arc on its own merits.

As I fleshed out my characters, I realized that I had to include an aspect of anime particularly personal to me: an exploration of gender and sexuality as something more fluid.

I watched Satoshi Kon’s 2003 film Tokyo Godfathers a decade after it was released and still considered it a pioneering neutral-affirming trans character depiction. Since then I’ve encountered (generally) thoughtful treatment of trans and gender-nonconforming characters in series like Paradise Kiss, Our Dusk at Dawn, Blue Period, and Wonder Egg Priority. Though the most popular anime series still do their part to cringily codify heteronormative gender roles, iconic juggernauts Hunter x Hunter and One Piece have broken ground in introducing trans characters in pivotal roles. Relationships and identities that were once subtext can now enjoy the full breadth and depth of anime’s aesthetic freedom.

But despite the increasing prominence of “marginalized” identities in media, any cultural observer can glean that the boundaries of art seem to be contracting as an increasingly reactionary chorus demands a static definition of gender and identity. Though anime isn’t immune to that conservatism, its existence as an artform that pushes the limits of believability makes it a unique weapon in the generations-long fight between the “real” present and the imagined future.

Anime isn’t the only arrow in my quiver as I take aim at the forces that would rather erase me and people like me. But it’s the one that might just fly the furthest, arriving at a story that seeks to expand our perceivable universe, where emotions spill off the page like meteor showers and characters act not in the ways they should, but in the ways they would, in a world freed just a little from the cel of reality. Carrying my lone melody like a satchel of seeds, a Golden Record for far-off gardens, to grow into new songs far from home.

______________________________

Beating Heart Baby by Lio Min is available from Flatiron

Lio Min

Lio Min has listened to, played and performed, and written about music for most of their life. Their debut novel Beating Heart Baby is about boys, bands, and Los Angeles. They've profiled and interviewed acts including Japanese Breakfast, Rina Sawayama, MUNA, Caroline Polachek, Christine and the Queens, Raveena, Tei Shi, Speedy Ortiz, and Mitski.