The Monstrousness Lurking Inside Motherhood

Amanda Parrish Morgan on Claire Dederer, Mary Shelley, Rachel Yoder, and the Warped Self

English teachers, myself included, like to correct people who conflate Dr. Frankenstein with his monster, but recently I’ve started to consider the possibility that the misnomer speaks to a fundamental equation of artists with monsters.

Jenny Ofill introduced the term “art monster” in her novel Dept. of Speculation. Shortly after having her first child, the novel’s nameless narrator reflects on the path she might have taken, were it not for motherhood:

My plan was to never get married. I was going to be an art monster instead. Women almost never become art monsters because art monsters only concern themselves with art, never mundane things. Nabokov didn’t even fold his own umbrella. Vera licked his stamps for him.

Ofill’s novel and its narrator have become synonymous with broader conversations about writing and motherhood in the time since I first read her work. In the years when my own children were babies, I read art monster essays from all sorts of writers I admire, women like Claire Dederer and Kim Brooks and Rufi Thorpe, often scrolling through them on my phone while I nursed Thea and later Simon.

In these pieces, the authors sought to push back, expand, re-claim, and reject the art monster trope in a way that made room for a kind of visceral motherhood that was complimented, not at odds, with the monstrousness that’s perhaps inherent, however faint, in creating any kind of art—or, in creating anything at all.

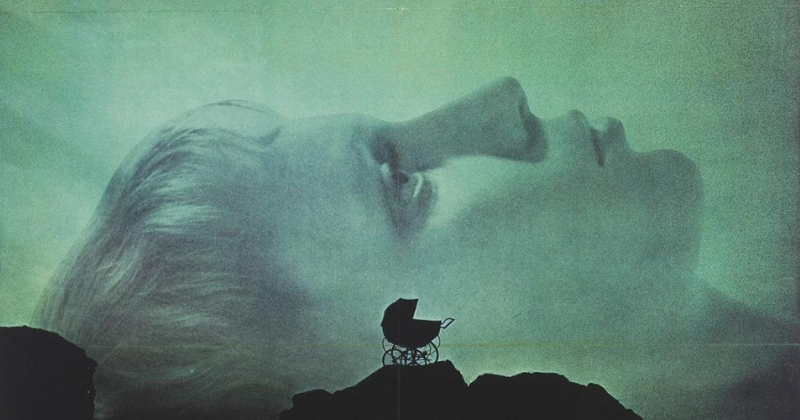

In a 2017 Paris Review essay “What Do We Do With the Art of Monstrous Men?” pondering Manhattan and Rosemary’s Baby and other work whose artistic merit had long been lauded in spite of the exploitative or even monstrous behavior of its creators, Claire Dederer invoked Offill’s idea, wondering: “If I were more selfish, would my work be better? Should I aspire to greater selfishness? Every writer-mother I know has asked herself this question.”

Again and again, Dederer asks, if their art was transcendent enough, then were the costs worth it?

The monstrous writer-mother that Ofill’s term refers to and Dederer considers is exemplified by women like Doris Lessing who left her children in order to write in London and Sylvia Plath who left her children behind via suicide. Plaths’ “self-crime was bad enough,” writers Dederer, “but worse still: the children whose nursery she taped off beforehand. Never mind the bread and milk she set out for them, a kind of terrible poem unto itself. She dreamed of eating men like air, but what was truly monstrous was simply leaving her children motherless.”

In Monsters: A Fan’s Dilemma, Dederer’s book that grew out of the Paris Review essay, she sees in herself the potential for a kind of monstrousness as well. It is easy to condemn artist men like Woody Allen or Bill Cosby who are monstrous in concrete, public, mostly-agreed upon ways, she argues, but our ongoing fascination with these “appalling geniuses” is a tell that we recognize something of ourselves in them. Again and again, Dederer asks, if their art was transcendent enough, then were the costs worth it? Can we get past the stain? How can we get past our own, more slight perversions?

“Sure,” Dederer writes:

I’m attuned to my children and thoughtful with my friends; I keep a cozy house, listen to my husband, and am reasonably kind to my parents. In everyday deed and thought, I’m a decent-enough human. But I’m something else as well, something vaguely resembling a, well, monster. The Victorians understood this feeling; it’s why they gave us the stark bifurcations of Dorian Gray, of Jekyll and Hyde. I suppose this is the human condition, this sneaking suspicion of our own badness. It lies at the heart of our fascination with people who do awful things. Something in us—in me—chimes to that awfulness, recognizes it in myself, is horrified by that recognition, and then thrills to the drama of loudly denouncing the monster in question.

In “Mother, Writer, Monster, Maid,” Rufi Thorpe writes of the Jekyll/Hyde or Mother/Monster dichotomy and the questions it begs about the relationship between self and shadow in the context of motherhood:

As much as I want to be a good writer, I also want to be a good mother. I even want to be the one who cooks dinner. I may complain about being the only one who keeps track of the ornate minutiae of preschool (bring an egg carton by Friday! We need $10 for costumes for the play! Remember: Thursday is a half-day!), but I also don’t want anyone else taking over this sometimes loathsome task. Life with small children takes place in the minutiae. Everything is in the now, and so if you are not part of the now, you miss it.

The now and the minutiae are the kind of thing I’d once rolled my eyes over and are also inseparable from what it has meant for me to care for Thea and Simon. Even the loathsome tasks—being vomited on, enforcing consequences, standing awkwardly with the other mothers at the side of the playground—I don’t want anyone else taking them over.

When Simon wakes up before dawn and tiptoes into my office while I’m finishing a draft of an essay, I want to work uninterrupted, but I also want to pull the weight of his body onto my lap for as many mornings more as he wants me to, to simultaneously be able to lose myself to my work and to lose myself to their care. Whether I commit to the child or the work, part of me becomes gnarled and neglected, because we can’t separate the artist from the mother. Dederer again:

When women do what needs to be done in order to write or make art, we sometimes feel like terrible mothers. Oops, slipped into “we.” When I do the writing that needs to be done, I sometimes feel like a terrible mother. And because motherhood is so close to the core of me, I feel like a terrible person. Like a monster.

*

Rachel Yoder’s novel 2021 Nightbitch opens with the mother of a toddler beginning to suspect that she’s turning into a dog, or at least that at night she’s becoming something like a tame werewolf. She notices a thick patch of hair, an itching at the base of her spine where a tail wants to erupt. She craves raw meat and longs to care for her son as a dog would—by licking his cheeks and nuzzling against him in a den.

Writing for The New Yorker, Hillary Kelly puts Nightbitch in “Mary Shelley territory—mother as inadvertent creator of monstrosity.” It’s not that Nightbitch is a monster, it’s that she’s created one. The visceral, sublime, consuming, and even violent impulses of creation are inseparable from motherhood itself. It’s never her son that Nightbitch wants to escape but the conventions of de-fanged motherhood.

I felt a fierce protectiveness of that impulse and energy that felt not at odds with motherhood, but directly in some kind of manic cooperation with it.

While Dr. Frankenstein transfers his longings into his innominate monster, and inadvertently sets it loose to prowl the woods and learn about the goodness of the Lord, the mommy monster of Nightbitch licks the blood off her new fangs with satisfaction. Rage, violence, and broken bunny necks aren’t crimes; they’re exhumed artifacts of our animal selves. We’re all monsters anyway, so why not allow ourselves to find power in the animalistic nature of motherhood?

The novel is funny, satirizing library baby story-time cliques, the tension between mothers who do and don’t work outside the home, and MLM recruitment invitations that arrive over Facebook bearing an excess of exclamation points and promising wine. All the mothers have an inner beast it turns out, no matter which camp they’re in.

Nightbitch is a monster, not just because she sprouts that tail and kills the family cat, but because she refuses to cordon off the self that creates art from the self that created her son. Her art, a performance piece in which she turns into a dog—metaphorically or through costume and makeup or literally, I’m not sure—and kills live bunnies and plays with their bones, ends with her son standing holding the limp animals and covered in their blood.

But Nightbitch’s most menacing monstrosity is perhaps most present before she finds a way to integrate the artist self with the mother self. It’s when she realizes that she in fact, has a vast wealth of knowledge that spans the artistic, maternal, and even the feral that she sees worth in what she creates as both a mother and an artist. Just as being an artist might be said to require a degree of monstrosity, so might motherhood. And she welcomes it:

She can revert to a pure, throbbing state. She had that freedom when she gave birth, had screamed and shat and sworn and would have killed had she needed to.

Since becoming a mother, I have thought often about what I know how to make (or don’t). I have thought about all the ways my mother and my grandmothers made whole worlds—with yarn and flour and sugar and record-keeping and story-telling—and because it was outside the confines of academies or institutions, it did not occur to me that this was also a kind of art. Motherhood need not to be at odds with art, nor does it need to entail monstrosity.

Deborah Eisenberg once said, of the incompatibility she’s observed between motherhood and art-making that “the point of art is to unsettle, to question, to disturb what is comfortable and safe. And that shouldn’t be anyone’s goal as a parent.” Nightbitch’s art is unsettling for its violence, but it’s also shocking because in performing it she reveals the animalistic nature of both motherhood and artistic ambition to the audience of other mothers who have assembled to watch and to her son. At the same time, she frees herself from the monstrousness that comes from self-erasure.

“What if writing motherhood is the frontier, is the uncharted territory into which we must step if literature is to advance?” asks Thorpe. And, perhaps Lessing, who looms large on the Art Monster list, might be said to have done just that in The Golden Notebook—gone to the frontier of writing motherhood, made possible only by her monstrosity.

Do the ends justify the means?

*

In the years before I had Thea, I attended a Monday night writing class at Rachel Basch’s house. We writers there were all women, and I was the only one who was not yet a mother. We were a focused group and did not do a lot of chatting, but over the course of years of reading one another’s work and sipping coffee in our mid-class break, I learned about the lives they’d driven away from to meet in that rural Connecticut living room.

Sometimes, I’d latch on to a phrase and store it away, like the time Rachel described writing two novels over years of nap times that carried through the early stages of her children’s lives. I couldn’t quite imagine what this meant, but I had an image of her sitting near her front window, afternoon light streaming in, scribbling away by hand as fast as she possibly could.

It’s Jekyll’s attempt to compartmentalize his most monstrous impulses that, ironically, makes them uncontrollable.

The fall I was pregnant I stopped working on my first book, a novel I’d been wrestling with for years, and found myself unable to write anything except for essays about pregnancy. A lot of what I wrote was about feeling trapped in this strange phase between being a parent and not being a parent. I wrote about pregnancy message boards and the shame I felt when I failed my glucose screening and the friends I felt slipping away well before Thea arrived. I wrote a lot about what I was afraid I’d lose—the speed in my legs, the hours in my day, the professional identity I was simultaneously relying on to define myself and eager to step away from.

In the enormous anxiety I felt waiting was also an enormous impatience: I wanted to start being a mother, to meet the baby we’d already decided to name Thea. I was terrified that something horrible would happen—that she would die before she was born, or that I would die in childbirth and never get to take care of her.

I also worried about a different kind of loss—one that was less frightening than death of course, but also difficult to talk about. I already knew I planned to leave high school teaching and I was eager to do so. I felt burned out from the red tape of public schools and frustrated with the demands of entitled parents in my district. I wanted, at least for a little while, to turn my attention homeward.

Logically, I reasoned that I’d still have relationships with students through coaching cross country and track in the afternoons and teaching writing workshops in the summer. But, I was also worried that I’d lose the sense of worth I’d long derived from teaching, that despite how low I knew it ranked on the hierarchy of impressive careers, it still ranked higher than mother.

Having children means, in one form or another, releasing what we most wish to sublimate into the world. Even when we get things “right” as parents, we’re no better able to control the outcome than Victor Frankenstein is able to create the perfect companion. The threat of monstrousness leaves an imprint on how we parent.

To make a human or world or a monster means facing the complicated, sometimes dark, nature of creating. I’d worried so much that I’d lose the part of me that wrote, or worse, the part of me that had the desire to write. Instead, I felt a fierce protectiveness of that impulse and energy that felt not at odds with motherhood, but directly in some kind of manic cooperation with it. I’d created a person, jumped into a life in some ways unrecognizable from the one I’d lived for the first 33 years of my life, and yet—here were words I still felt an animalistic need to get on the page not in spite of being a mother but, in some ways, because of it.

In Jekyll and Hyde, the story of a good man’s attempts to control his dark self, it’s not only Hyde’s actions responsible for the suffering in Edinborough, it’s Jekyll’s attempt to compartmentalize his most monstrous impulses that, ironically, makes them uncontrollable.

As I was finishing this essay, I mentioned to my friend and former high school teaching colleague that I was writing about Frankenstein. “I just taught it!” she exclaimed, “That poor creature. All he wants is to be loved by the man who created him.”

In all the thinking I’d been doing about creating and abandoning and resisting—both intuitively and intellectually—I had not thought about the key fact that neither Nightbitch nor Dederer abandon what they create.

Unlike Dr. Frankenstein or Doris Lessing, or even the woman Nightbitch might have been during the early pages of the book, they abandon neither their art nor their children. There, in the book’s climax, is Nightbitch on stage with her son. And here is Dederer’s book, and throughout it, the ways being a mother has shaped the way she’s made and responded to the art around her.

Amanda Parrish Morgan

Amanda Parrish Morgan is a College Writing instructor at Fairfield University, USA, and Westport Writers’ Workshop instructor. Her work has appeared in The Washington Post, Guernica, The Millions, The Rumpus, The American Scholar, Women’s Running, JSTOR Daily, Ploughshares, and N+1, among others. Stroller was named to The New Yorker's Best Books of 2022 So Far.