To understand Charles Perrault better, we should perhaps explain a little of the labyrinthian path that has led him to this salon.

He is born into a bourgeois family, for example, and at fifteen drops out of school, so he considers himself a self-made man—though like almost every self-made man, if you turn him upside down and shake him the coins and tokens of privilege come tumbling from his pockets: in his case, a costly law degree and a job as secretary to his brother, the tax receiver of Paris.

In his early years, his fondness for finding morals expresses itself through rebellion, as he dallies earnestly with Jansenism and opposition to the Crown, but fear and age make a pragmatist of him—his literary ambitions only take off, he discovers, after he writes rather banal and sentimental poems celebrating the marriage of Louis XIV and the birth of the Dauphin, and he learns his lesson. Then fate has it that his dear friend Jean-Baptiste Colbert sees some spark in him and decides that Charles is to be his protégé. Thanks to this great benevolence, in 1671 he—he, Charles Perrault!—is elected to the French Academy, and finds himself in charge of the royal buildings at Versailles.

Versailles! It’s hard to explain how much power the word has. It was once the site of a simple hunting lodge, but Louis has replaced it with a vast, seething royal residence unlike any other in the world. By 1682, the king has even made it the seat of government; the de facto capital of France. It is a city of the rich, a living fairy tale, Louis XIV’s fever-dream—and all of it in the open, so any tourist can stroll in and gawp! Here, let us join the tourists in wandering around.

Everything rotates around Louis XIV, of course, the Sun King whose robes are as splendid as stars; whose getting-up and going-to-bed ceremonies structure the day; whose preference for orange trees means they are everywhere in Versailles, in silver pots, the smell of their blossom mingling with the scent of urine (there are no toilets, only chamber pots and corners) and nobles who bathe just once a year. There are bowls of petals everywhere, too, to sweeten the air, and the furniture and all visitors are sprayed with perfume—it is often known as the “Perfumed Court” though nothing quite disguises the uric fug in the crowded corridors.

Let us walk through one such braying traffic jam of sedan chairs, beneath the corbelling in stucco and gilt. The king feels safest with all his nobles here, under his constant observation, as if Versailles is some early prototype for the panopticon. They are constantly under his gaze—if not literally, then figuratively for Louis spends much of his time posing for artists and his portrait is on every wall; his face, surrounded by the sun’s rays, gilded upon each door you close softly for privacy; his head on every plinth. He struts and gallops across every ceiling. (Reproductions of such images have been turned into engravings now, and distributed widely across the country along with the casts of the statues, such is the king’s desire to be “everywhere.”)

Those curiously tall women you see are walking on stilts called “pins” to lift their silk shoes out of the mud, and from their height sometimes feel like goddesses gazing down on clouds from Olympus, so busy is the room with preened puffs of grey and silver hair. Cows and asses stumble around, providing fresh milk for the king’s many children, pushing their large wet noses into embroidered velvet curtains; rubbing their haunches beneath Titians and Raphaels.

There is Syrian storyteller Hanna Diyab, introducing the court to the wonder-tale of Ali Baba in his baggy trousers, a dagger tucked in his belt and a jerboa under his arm. The queen herself half-listens, grey-toothed from too much garlic and chocolate, surrounded by her little friends and yappy dogs. It’s rumoured that one of her daughters with the king was born completely black, and so they keep her in a convent near Melun.

Of course, you must get used to the constant hammering of building work; dust; scaffolds. That is Charles’s doing. Versailles grows every day, as though its tools are under some magician’s enchantment and cannot be stopped. The south wing is for the princes of blood (the king’s illegitimate family), the north wing for the hundreds of nobles. More than a thousand and five hundred servants lodge here too—each role often inherited and jealously guarded: the mole-catchers are the Liard family, for example, the Francines are in charge of fountains, several generations of the Bontemps have been valets de chambre, whilst the Mouthiers are cooks.

One hundred men having watched him get combed and dressed, the king’s procession is now making its way beneath the chandeliers, through the hall of looking glasses: a wonder that required the establishment of a royal glassworks, and the poaching of the finest mirror-makers and their industrial secrets from the Venetians. It floods with light from the big windows, reflected back by the gilt-framed windows of the mirrors. Can you glimpse the man himself through the simpering crowd that call out to him with their requests; slip messages into his hands? He adores shoes, so is wearing a pair that add four inches to his meagre height—diamond-buckled; leather the cream colour of scallop-meat, with roe-coloured straps and heels. Ivory tights show off his muscular dancer’s thighs. A little belly hangs above them, a sign of wealth and fashion—some men at court have taken to padding their midriffs in mimicry. The royal robes are decorated with golden lilies and trimmed with ermine fur, and perched on top of the king’s head is one of his vast collection of wigs: an enormous hive of dark curls chosen to make him look taller and virile. Lost amidst it all is that small, delicate-featured face—rosebud-lipped, shy with smallpox scars. A face you might take for that of a sweet little governess, were it not framed by such masculine pomp.

And we can see behind him, amongst the courtiers, the king’s brother—Monsieur, as he’s known—painted and powdered, his eyelashes gummed together; blinding with dazzle. His first wife was poisoned by a couple of his special boys. The king’s son, the Grand Dauphin, is there too—tall, fair, and broad, and obsessed with hunting. The Dauphin is generally viewed as a harmless lunk, though he has killed all the wolves in the Île-de-France—once six in one day—and before his own death will ensure they are extinct. The memoirist Saint-Simon famously notes that he is “quite without vice, virtue, knowledge, or understanding.”

After a trip to the royal chapel, in the afternoon the king will hunt in the forest, or go for a walk in the gardens. Come, let’s go outside so we can show you the gardens! The king so loves a tulip that he imports four million bulbs a year from Dutch nurseries, whilst there are also abundant tuberoses, stocks, wallflowers, daffodils, jasmine, hundreds of fruit trees. There are thousands of fountains, ejaculating spumily with thousands of choreographed water jets. An orangery, with its universe upon universe of ripening suns.

What a view when you step out! The grand perspective. The gardener Le Nôtre’s creation, every detail reviewed by the king himself. It is a God’s-eye view: revealing a vast, intricate pattern of which those mortals below you, in the midst of it, are unaware. The symmetrical rectangular pools are positioned to reflect the sun’s rays back on the palace. Then Latona’s fountain, its golden frogs belching out water. The knotted paths and gardens; the box hedges; the parallel rows of statues down the sides of the great lawn, which unfurls like a green carpet, with sheltered groves on either side, and—far beyond, at the end of it—Apollo’s fountain, in which the sun-god drives his chariot to light the sky. In the hazy distance the Grand Canal, where they have been known to stage sea battles; where the king and his friends go on gondolas that, with their costumed sailors who sing serenades, were a gift from Venice. Come, let’s go to the maze with its sixteen-foot-high box hedges, designed by Perrault himself, who advised Louis XIV to include thirty-nine fountains each representing one of Aesop’s fables. Water jets spurt from the animals’ mouths to give the charming impression of speech between the creatures, powered by waterwheels on the Seine. Within here are the Owl and Birds, the Eagle and Fox, the Peacock and Jackdaw, the Wolf and Heron, the Tortoise and Hare, the Council of Mice. The young Dauphin, you see, loved the fables, so it was conceived to educate and delight him—there is a bronze plaque with a caption and quatrain next to each fountain, from which the king’s son learned to read. Now it is a fashionable place for romantic assignations, young people entering with their little guidebooks bound in red Moroccan leather, a fact that makes

Charles warm with pride.

Whilst we’re out here, too, twenty minutes’ walk from the palace is the king’s menagerie, with an iron balcony at its centre, the courtyards radiating out from it in sun-like spokes. The rhino is a suit of armour sprung to life; porcupines bristle with spindles. That cursed prince, the lion, licks his paws. The king is fond of animals, uninterested as they are in political gain, so makes sure that his pockets are always full of dog biscuits baked by the pastry chef. His dogs have their own cabinet des chiens, their veneered walnut beds lined with crimson velvet.

Every evening, after dinner, more pleasures; more wonders! Chandeliers flicker with a hundred thousand dripping candles in the Grand Appartement, where there is gambling—card games such as reversi or hocca, a sort of crooked roulette banned by the Pope, as well as aristocrats steadily sobbing in corners, stripped of jewels as if by highwaymen. There is a theatre hung with crystal lamps and tapestries that stages fabulous entertainments: plays with French and Italian actors; operas; the king’s beloved ballet. One performance, The Four Seasons, involves some of his wild beasts: Summer riding in on an elephant; Autumn astride a camel; Winter hanging tensely off the back of his bear. If the king does not have too many letters prepared by his secretary to sign, he may join the audience, or even take part himself—just recently he played the god Neptune in a comedy-ballet. Other nights there are fancy-dress balls or masked balls.

Fireworks sometimes hurl themselves in the sky: a giant’s white roses. Golden eggs breaking against a dark wall.

Finally, each night, the crowd gather at the king’s ante-chamber to attend the dinner of the Royal Table. Another grand ritual: four soups—his favourite being crayfish in a silver bowl—sole in a small dish, fried eggs, a whole pheasant with redcurrant jelly, a whole partridge or duck (depending on the season) stuffed with truffles, salads, mutton, ham, pastry, fruit, compote, preserves, cakes. All stone-cold, for the kitchen is so far away that the king has never experienced a hot meal, and eaten largely with hands, for nor has he ever touched that new-fangled device the fork. For special occasions entire tiered gardens of desserts form pyramids on the table: precariously balanced exotic fruits, jellies, and sweet pastes; sorbets scented with amber and musk; the wonders of the ancient world recreated in spun-sugar and pâte morte; gingerbread palaces.

The king’s appetite is legendary. At his autopsy, years later, they will find his bowels are twice the normal length. This is all the more remarkable given that years ago, whilst extracting his teeth, a part of his maxilla was accidentally removed, which makes him slow to chew and causes scraps of food to bubble out of his nose whilst eating, a fact about which he has decided to be scrupulously unembarrassed. These banquets have attained such importance within the court that when one chef, Vatel, sent the fish out late, it did not seem disproportionate that he then plunged a knife into his own heart in shame.

Poor Vatel, Perrault liked him: always focused on a piping bag, or tasting, stirring, darting around the kitchen with the energy of a grasshopper. Such a perfectionist about pastries! How he wishes he had told him: Vatel, it does not matter. Everything is just demolished after all by teeth and guts, then shat out into pots. Fuel for the royal maw. Even after such feasts, the king likes to finish by taking a handful of candied fruits, for the going-to-bed ceremony. It is his talent, his tragic flaw, and his raison d’être that he always wants more.

And talking of bed and more, we must also mention the fucking. Did you see that maiden make eyes at you through her mask, adjusting the apples of her breasts? Did his crotch shove up against you in the corridor? They are all at it, constantly, gluey with fucking; dripping with fucking. Marriage is a political arrangement, quite separate from love, and not to enter into extramarital affairs a little gauche. This is a Paradise of Penises; a Cockaigne of Cunts. There are no common whores, of course—orders have been issued that if they are found within two leagues of Versailles, they will have their nose and ears cut off—but courtesans are quite another matter. The king has numerous mistresses, after all. Since he lost his virginity at fifteen to forty-year-old “One-eyed Catherine,” no girl has been safe, whether maid or noble. He takes his pleasure all over Versailles: beds, chaises longues, doorframes—a favourite is the Hall of Mirrors, unsurprisingly. He even has official and unofficial mistresses! The king’s current official mistress is Madame de Montespan—or Athénaïs, as she likes to be known, and which we shall agree to given the preponderance of madames—a woman of incredible power, and a diva both fabulous and frightening, depending who is asked.

You will not see Athénaïs today, though—she is receiving intimate friends in the marble baths. Whilst the king has only had three baths in his life for health reasons, Athénaïs loves to bask in water scented with vanilla, thus announcing her presence with a waft of haunting, smothering sweetness, like she pisses icing and shits custard.

Was there ever a place like this on earth? Is it not the apogee of human civilization, so intricately unnatural; pure artifice; that very castle in the clouds humans have always dreamt of? The perfect ending for every Mother Goose’s story?

__________________________________

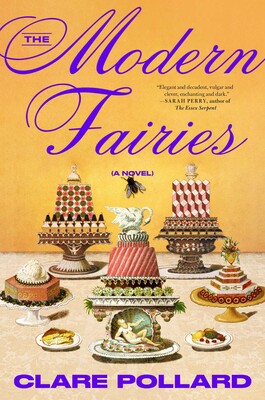

From The Modern Fairies by Clare Pollard. Copyright © 2024. Reprinted by permission of Avid Reader Press, an Imprint of Simon & Schuster.