The Miracle of Black Love: On the Greater Meaning of My Parents’ Enduring Marriage

Farah Jasmine Griffin Considers James Baldwin and Beautifully Doomed Urban Couples in Literature

In my family and community, my parents’ love story was legendary. Recounting elements of it, tellers of the tale—aunts and uncles, cousins and neighbors, friends and casual observers—all seemed to find warmth and contentment. At first, my parents were buoyed by their youth—his brilliance and ambition, her fresh-faced beauty, creativity, and resourcefulness. Later, his addiction and ongoing attempts to rid himself of it halted their momentum, but not their devotion to each other.

Having met as children, Em and Mena were portrayed as a Black Romeo and Juliet, without the family feud. By some accounts she was 12, too young for boy company, and he was 13, when they first met over games of jacks and double-dutch. She was the baby girl of a big brood that included two protective older sisters and a bevy of cousins, uncles, aunts, and grandparents, all of whom at one point or another shared living space. He was the young prince, the only child, of a striving young couple: the joy of his mother’s life and the object of his contractor stepfather’s resentment. He never knew his birth father, and did not know Alonzo Griffin was not his biological father until the day of his mother’s funeral, when he was 40 years old.

Mena and Em were new teen parents, aged 15 and 16, when they ran away to marry, but a judge refused to render the service without Mena’s parent’s signature. Their baby daughter, Myra, continued to live with his parents even after the young couple successfully eloped. Finding their names in a Philadelphia Inquirer list of Applications for Marriage Licenses is an invitation to imagine them on the cusp of the life they would build together. She is listed by her maiden name, Wilhelmena Carson, living in the Ellsworth Street home I most identify with my grandmother, and he still resides in his parents’ home, just around the corner from hers on Federal Street.

Following a brief stint in the Navy just after the end of World War II, and with the assistance of the GI Bill, Em purchased a house for his young bride from an Italian numbers runner, and earned an Associate’s Degree in Architectural Engineering from Temple University. Blueprints and T squares found their way into the South Philadelphia row house he renovated over and over, while dreaming of furthering his education and making his way as an architect. Mena recalls standing on the sidewalk with him, looking up into the windows of architectural firms that didn’t employ Blacks. The streets of Philadelphia were littered with many such places that practiced this unobtrusive form of discrimination. Yet, the couple’s dreams were refreshed by going to jazz clubs like Pep’s at Broad and South, or the basement of the Douglass Hotel, which housed the Showboat, near Broad and Lombard, where they heard the latest cutting-edge musical innovations of their peers. He befriended many of the musicians and she recalls him introducing her to a young Miles Davis (“shy”) and to Charlie Parker. They sat near the edge of the stage to watch and listen as Billie Holiday serenaded and mesmerized them.

Early mornings, before heading off to their jobs, they could be found swimming in the Wissahickon Creek, where they also filled jugs with fresh spring water. Mena found steady work in Philadelphia’s many garment factories; in the evenings and on weekends she made clothing and did alterations for local women. Like many other degreed Black men, Em worked for the Post Office. He drove a “Dynaflow” Buick; she acquired a taste for D’Orsay pumps. Occasionally they drove to New York to visit friends on Sugar Hill in Harlem or to attend boxing matches at Madison Square Garden. Rare photos of them from this period show them dressed up amid friends, laughing and enjoying what must have been a rich social life. As a curious girl I found old paper coasters and cocktail napkins embossed with “Mena & Em,” further evidence that they hosted parties I’d never witnessed, evidence of a mysterious and distanced life that preceded my entrance into their world.

Later, when my father became addicted, the plans for bigger homes and better jobs became ever more elusive. They settled into a life haunted by the anxiety of discovery by police, and worked as skilled laborers—she in factories and he in a shipyard—and gave birth to a second baby girl, whom they named Farah Jasmine.

My mother stayed on, through disappointment and setbacks. My father became a high-functioning addict, working every day and making various efforts to rid himself of his habit: methadone, group therapy, cold turkey. There were encounters with the police, and a year before my birth, he served a four-month-long stint in prison for possession of the “residue of heroin.” Throughout it all they leaned on the myth and reality of their romance. They were supported and sustained by loved ones, and they painstakingly mapped out a future for their youngest child. Guided by his vision and her ingenuity, I followed a path that generations of Civil Rights activists opened.

Their relationship was as passionate as it was affectionate, as playful as it was deadly serious.

I first heard the love story from him. On the way to the library, as we passed familiar small businesses—corner stores, Italian bakeries, hardware stores—through the thoroughfare of Point Breeze Avenue, he relayed a fairy tale complete with a beautiful princess and her two sisters—One Eye and Three Eye—and a Prince Charming. Once we reached our destination, he scooped me in his arms and revealed that the sisters were “your aunts, Eartha and Eunice,” the Princess, my mother, and, of course, he was the rescuing, heroic Prince. (Many years later when I heard Mary Lou Williams’s “The Land of Oo-Bla-Dee,” I realized my father’s fairy tale was suspiciously similar.) Walking to my grandmother’s home, in whose care my mother left me while she worked, she told me stories of eloping, describing in detail the dress she made and wore: “It was black with red rose print; in the back at the bottom of the V, I sewed a big red bow.” Because of them, I never fantasized about being a princess bride, the center of attention at a big wedding. Eloping seemed so much more romantic. My aunts’ and neighbors’ versions of the story were recounted with soft, pleasant smiles. “Your daddy loved himself some Mena,” said Aunt Eunice. Aunt Eartha recalled, “He bought her a house and filled it with furniture.” And one of our neighbors, an older lady, told me, “I loved watching them holding hands when they came home in the evening.”

Everyone seemed invested in the couple, who at one point or another represented possibility, love, marriage, education, homeownership, and upward mobility. Later, they were an example of commitment and resilience in the face of life’s challenges. My childhood friends watched in a kind of admiring disbelief at my parents’ displays of affection. Their relationship was as passionate as it was affectionate, as playful as it was deadly serious. At his funeral, his life was framed by a version of their story, his final words reported as “Take me home to Muzzy.” (Even then, I knew these were not his final words, because I had heard them in the ambulance. When the police van sharply turned the corner and the stretcher slid back, he hit his head and said, “Oh Muzzy, my head!” But that was too painful to recall and relay. The fairy tale needed a better ending.)

That story, their story, so often told, so celebrated and mourned, was nonetheless full of its own silence. No one mentioned the addiction that slowed their ambitious trajectory. Though known within our small, tight family circle, it was a secret, our family secret. These were the days before naloxone and sympathetic portrayals of opioid addicts on television and in print. These were the days when the possession of the smallest amount of narcotics guaranteed prison, and neither mercy nor sympathy. These were days when the public face of the heroin addict was a Black man, often a musician, not a young white person. (Although I vaguely remember discovering an issue of Life magazine that my father had saved along with the Ebonys, Sepias, and other Black magazines, featuring a photo essay about a young white couple, both addicts.) There was no space in the public imagination for an intelligent, high-functioning addict, especially not a Black working-class one. So, we kept it a secret because so much was at stake: our beloved head of household, our well-being, our home. I was an inquisitive child who asked many questions, which my mother always answered, those answers followed by “Shush, you can ask me anything, but remember, we don’t talk about these things to other people. Don’t tell our family’s business. Your daddy loves you.”

As a child, I had no doubt of his love; I was fully aware that he cherished me. I knew that though he didn’t celebrate Christmas, the season would bring shopping sprees, new dolls, shoes, and musical instruments, all bought by my father and not “some fat, white man in a red suit.” I knew he worked hard to provide for us, going to work even on days when he didn’t feel well. I knew that he dealt with small racist encounters on an almost daily basis; he recounted them at night when he returned home.

And yet, even as a small girl, I instinctively felt more secure in the presence of my mother than my father. My child’s understanding of it was that though he would want to save me from an oncoming car or bus, my father’s reflexes might be too slow to jump into action. My mother, on the other hand, would snatch me from harm’s way in the blink of an eye, and if necessary, she would throw herself in front of the lethal vehicle. I trusted her judgment and her ability to handle anything that came our way.

Following my father’s death, their story took on greater meaning. It was told to me to remind me that I was the product of Love. That no matter what the world, white people, and later bourgeois Black people, might think or say, my parents loved and respected each other and I was a result of that. My well-being, my gifts, my successes were a result of their investment in and of love.

At the core, romantic love in Baldwin’s writings can be the source of an ethics of community, of a radical spiritual survival, in a place set on destroying our souls.

For years I sought their story in books. Less Zora Neale Hurston’s Teacake and Janie of Their Eyes Were Watching God, whom I would later discover, they were to my mind more like the young, beautifully doomed urban couples of James Baldwin’s novels: Elizabeth and Richard of Go Tell It on the Mountain, Tish and Fonny of If Beale Street Could Talk. Both bear witness to the miracle of Black love in this hateful and unjust place we call home. Both have artistic, intellectual male leads, too sensitive for the raw and brutal injustices they encounter on an almost daily basis. And, the women are young, fiercely devoted, finding a deep inner strength they didn’t know they possessed. (In “Sonny’s Blues,” Baldwin also writes about an addict with incredible sensitivity, and I love him for it.)

I read Baldwin as a teenager, about the same age that Mena and Em were when they had my sister. Go Tell It on the Mountain was my first James Baldwin. I read it the summer before I began attending The Baldwin School on scholarship. That summer of 1978 was my summer of James Baldwin. I recall reading Giovanni’s Room, If Beale Street Could Talk, and The Fire Next Time in quick succession. I read in the kitchen as my mother straightened my hair, I read in my bedroom, and on the bus, and when not reading I thought about the characters like they were friends or family. I eventually made my way to Giovanni’s Room Bookstore, on the corner of 12th and Pine, which I later found out was a gay bookstore. There, I was always greeted by kind and friendly white men, who welcomed me into their sunlit, book-filled space.

Fonny and Tish’s romance is a boy-girl love story that sits at the center of a larger family and community love story. It is about the ways Black people nurture and nourish each other in the midst of a society that shows them no love. There is hope in young love, particularly young love that will result in new life. There is the desire to make a way for them, a sense of possibility invested in them. This is the kind of investment I think my family and community made in my parents’ story. There was a softness that overcame them as they talked about how much Emerson loved Mena. The older women even laughed when they learned of their quarrels because they knew these were love spats, neither destructive nor mean-spirited. Their peers were both protective of and sustained by them. Their relationship had outlasted other teen romances. I sometimes wondered how a young couple came to bear so much.

In his fiction, Baldwin, unlike Richard Wright or Ralph Ellison, is attentive to Black women. And, because he is attentive to Black women, he is attentive to Black love, to the love Black people have for each other, to their capacity to love in spite of the hatreds directed toward them. Baldwin, a gay Black man, sees the beauty of Black women and Black people; he attends to their tenderness and their desire for each other. Wright seems unable to imagine this tenderness. Ellison, though clearly a lover of Black culture, does not display the same affection for Black women. Unlike Baldwin’s, Ellison’s women characters lack substance and depth. In contrast, Baldwin’s stories are often told from a woman’s perspective. Beale Street is narrated by Tish, in the first person. She is the voice of authority; her interpretation of events shapes the way the reader receives the story.

To claim love as a theme of Baldwin’s writing is almost cliché. Much has been written about his deep Christian sense of love as a requirement for and source of redemption for America. It is certainly an obsession of his, but religion isn’t where it starts for me. What initially struck me upon my first readings of Baldwin, what strikes me still, is the way he writes about romantic love between Black people, and the way that romantic love radiates out, or does not, into families and communities. At the core, romantic love in Baldwin’s writings can be the source of an ethics of community, of a radical spiritual survival, in a place set on destroying our souls. He does not romanticize Black life or the conditions under which Black people love each other. In fact, he explains them in harsh and unrelenting detail. These circumstances are what make love all the more profound, as miraculous as it is quotidian.

__________________________________

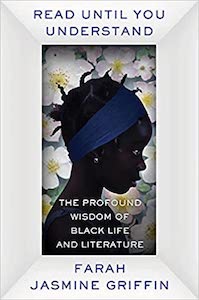

Excerpted from Read Until You Understand: The Profound Wisdom of Black Life and Literature. Used with the permission of the publisher, W. W. Norton & Company, Inc. Copyright © 2021 by Farah Jasmine Griffin.

Farah Jasmine Griffin

Farah Jasmine Griffin was the inaugural chair of the African American and African Diaspora Studies Department at Columbia University, where she is also William B. Ransford Professor of English and Comparative Literature. She is the author of numerous books and the recipient of a 2021 Guggenheim Fellowship.