Being married to an entire person was too much. It was too much to grasp. It was intimidating, overwhelming. She didn’t know how he could stand it, or when his method started. She figured everyone had their own method, inasmuch as it was endured, by and large. People found their method just when they were about to be crushed, before it was too late. Adapting a little at a time was hers; then things would be fine for a long while, until the method’s unresolved limit was reached. It was that dangerous area right around his nose, and, well, the nose itself, which she couldn’t handle. When the days of the nose arrived, she tried avoiding them, first by distracting herself, then with anxious, fake joviality: No, no, my friend, we’ll skip over you just this once. Goodness knows, who hasn’t been forced to stand in a corner or been a bench warmer one happy evening? It’s part of life, it’s the way the world is. She would try starting from scratch with the hands. But that never worked. The hands were deeply insulted and distant, in solidarity with the nose. Amazing how a body teams up so obstinately! Demands fairness. She let go of his hand and seized on his eyes, which stared cruelly at her, glassy and omniscient. It wouldn’t be their turn for a week. Her final option was to open all her pores and breathe in the whole person, a risky, suffocating moment, where a burnt smell of unfamiliar childhood seared her and curled her into an amoeba-like ball of simple self-maintenance. When, with difficulty, she crawled around the room, and little by little retrieved all the parts of her personality and patched them back together (though usually a few small fasteners were missing, which she later would find hidden away in cracks in the paneling or under the shelf liner in the pantry, and think indifferently that it was all part of his method, which wasn’t any of her business), his nose was noticeably softened and let itself be passed up without any particular resistance. This process was exhausting and caused her violent mood swings, which often drove her to seek reconciliation with the nose. She suggested they adopt a peaceful and vegetative truce, a friendly sibling relationship, a vigilant attentiveness toward handkerchiefs, with particular regard for the nose’s special interests, which of course were often ignored by the owner; but it was all in vain. The nose would settle for nothing less than love. It made such a nuisance of itself that, at a certain point, she changed the sequence and put it after the eye-days, which were the best of the month. She really loved the eyes and told them so without letting herself be disturbed by the voice, which ran in its own channel, completely satisfied with the formation of the couple upon the thin ice of the surface; satisfied with those days which belonged to it alone, with periodic certainty. She loved the eyes and gave herself to them and let their soft gleam penetrate deep inside her, so that for seconds at a time she forgot the threatening cliff on the lower level. To bolster her further, she added a vacation day between the eyes and the nose. After some practice, the trick worked. The man didn’t realize that he wasn’t there. He must never discover this, because it would have made his method impossible, regardless what it consisted of. They always respected one another’s methods without knowing the slightest bit about them, which is very common between people. But when the vacation day was over, that stupid lump of flesh was there again with its unavoidable demand. She should love it, take it in as her own. It stuck out of the bag when she was shopping. It clogged the keyhole, so it was as if the key had been made to fit a much smaller opening. In its cruel jadedness, the nose caused her countless small exasperations and pursued her nightly in her dreams in the most terrifying disguises. Only a few times over the course of the years had she been able to collect herself and avoid it. She might have been able to bear the enmity of the hands, the forehead, the ankles, and the shoulders, but not the eyes. For their sake she now always chose the dismembering escape route of the shatter-mechanism, and she got used to overlooking the nose’s vibrating insult, to the extent the eyes failed to see it. But she was never blind to the danger of her method. Another woman, she thought, would have probably found a better solution. A blotting-paper woman would have devoured him completely with no trouble, without even spitting out the hair and bones, and then she would have lain herself in a secret drawer, where everything was ready and well-kept, humidity retained by preserving fluid. But for her, so slippery and water-repellent, this method was the only one. Danger lay in the nose’s dissatisfaction, and in time she saw the situation approaching catastrophe. Her fate became unbearable; something had to give. It started insidiously. One morning when she was crawling around, blubbering and dispossessed, fumbling for her centrifugally split ego, she realized there were three nails missing as well as two gears, meaningless in themselves and which she rarely used. Ridden with anxiety she looked in the usual hiding places, and then all over the house, in the cellar, in the attic, and finally under the bushes and trees in the yard. All in vain. They were and would remain lost, and she never found them again. Not that anyone noticed. It wasn’t the kind of loss the world paid attention to. Yes, she discovered, her scalp tingling with fear, what a great deal of one’s self a person can lose while retaining the ability to function. It wasn’t until she kept falling out of rhythm, because it was hard for her to hear the music—but this was after a long time had passed, many, many years—that in her desperate loneliness she sought comfort at the eyes, her nicest friends. And when in the depth of the pupils she saw a glint like rusty metal, it was as if a damp rag was wrapping around her heart, and she realized that all the disappeared things had ended up there, somewhere inside her husband, and that he would never give them back to her, even if he wanted to. This was simply because he had no clue about the robbery. It was just the simple, consequential punishment for the defective method. Then an egotistical fiery column of horror rose up inside her, and she dropped her method immediately and completely, from one moment to the next, indifferent to others and determined only to preserve the few essential parts that had not yet been stolen from her. Indifferent to “getting through it.” The music was gone, and they stood completely still while people jostled them. Her eyes sought the nose, though it wasn’t its time yet. She saw it had grown bigger and was full and friendly, completely filled with her possessions and much too busy digesting them to keep paying her even the slightest attention. It had finally been satisfied. Its large, dilated nostrils turned away from her, and in limp, frigid jealousy she saw that they were turned toward a blotting-paper woman, who was dancing by at just that moment. She seemed to have congestion as well.

“Stay with me, nose,” muttered the remains of her voice, and with the resigned sniffle of a cold, the now highly dignified excrescence turned begrudgingly back in her direction. From now on it would live in the inextinguishable hope of taking her skeleton and skin too, all that was left.

But it never happened, now that anxiety and happiness had left her, along with her desire for the eyes. It would never happen, now that she was inhaling the whole person without difficulty. Now that it was possible, since it had swallowed so much of her. Most of life had passed. The music was audible again, and they danced better than before and without fatigue. Below the ice lay her abandoned method, completely covered by his, suffocated by it.

People said they were the happiest married couple they knew.

__________________________________

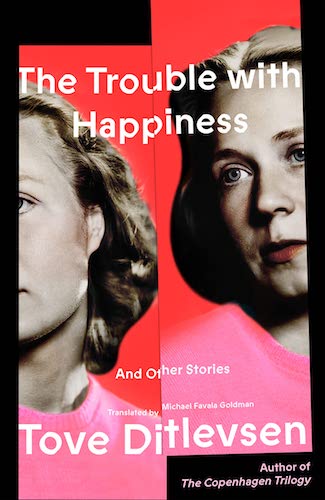

Excerpted from The Trouble with Happiness: And Other Stories by Tove Ditlevsen. Published by Farrar, Straus, and Giroux. Copyright © 1952, 1963 by Tove Ditlevsen & Hasselbalch, Copenhagen. Translation copyright © 2022 by Michael Favala Goldman. All rights reserved.