The Men Who Brought Political Radicalism to Oscar Wilde

On John Ruskin, William Morris, and the Nascent Anarchism of a Literary Icon

Oscar Wilde’s interest in the condition of the working class likely originated at Oxford, under the tutelage of John Ruskin, the moralist, art critic, hater of industrialism, advocate for economic justice, and enthusiast for Gothic architecture. The product of a strict Christian upbringing, Ruskin considered himself both a Tory and a communist. Though devoted to art’s specifically moral mission, he became a defender of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood and an inspiration to the Aesthetic movement.

Beauty, in Ruskin’s analysis, can only result from specific social conditions. It must be produced by skilled workers who are treated not as mere instruments for the ends of others but as creators in their own right and participants in the design of the works they produce. Likewise, it is the duty of the idealists and visionaries to take an active, practical hand in the work of improving the world, not only to guide and instruct but also to participate directly in the construction and completion of the realized product. The idea was to ease the hierarchical division of labor, under which, Ruskin complained, “it is not, truly speaking, the labour that is divided; but the men;—Divided into mere segments of men—broken into small fragments and crumbs of life.”

The industrial system of production requires:

one man to be always thinking, and another to be always working . . .

whereas the worker ought often to be thinking, and the thinker often to be working, and both should be gentlemen in the best sense. As it is, we make both ungentle, the one envying, the other despising, his brother; and the mass of society is made up of morbid thinkers and miserable workers. Now it is only by labour that thought can be made healthy, and only by thought that labour can be made happy, and the two cannot be separated with impunity. It would be well if all of us were good handicraftsmen in some kind, and the dishonor of manual labour done away with altogether.

And so it happened (as Wilde told the story) that at one of Ruskin’s Oxford lectures “he spoke to us not on art this time but on life. He thought, he said, that we should be working at something that would do good to other people, at something by which we might show that in all labour there is something noble.” Soon after, Ruskin “went out round Oxford and found two villages, Upper and Lower Hinksey, and between them there lay a great swamp, so that the villagers could not pass from one to the other without many miles of a round.” Ruskin recruited a group of undergraduates, Wilde among them, to gather in the mornings and build a flower-lined lane to connect the towns.

Calling themselves the “diggers”—coincidentally, perhaps, a name they shared with a sect of proto-anarchist Christian utopians who reclaimed the commons on St. George’s Hill during the English Civil War—the young men went out every morning, “day after day, and learned how to lay levels and to break stones, and to wheel barrows along a plank.” Together they “worked away for two months at our road.” Only, at last, “like a bad lecture it ended abruptly—in the middle of a swamp.” The school term over, Ruskin left for Venice, and the project was abandoned. But the experience planted in Wilde the idea “that if there was enough spirit amongst the young men to go out to such work as road-making for the sake of a noble ideal of life,” then it might also be possible to “create an artistic movement that might change . . . the face of England.”

*

As much as he admired Ruskin, ultimately Wilde’s views on handicraft, labor, workers, and socialism were shaped more by his acquaintance with another of Ruskin’s disciples, William Morris. Wilde’s early lectures contain much that is straight Morris. His focus on the decorative arts and the beauty of everyday objects, his disdain for the gaudy and the ill-made, his insistence that art become popular and that all classes of society be educated in practical craftwork, the desire to see art and labor joined, and his faith in the artisan as a rejuvenating element of society—all of these he learned from Morris.

Morris was a Marxist of a peculiarly artistic, humane, and libertarian variety—both a romantic and a revolutionary, a craftsman and a communist, a man celebrated for his individual genius and his public spirit. Morris was a kind of latter-day Renaissance man, a poet, a political visionary, a designer and manufacturer, a skilled artisan, and a spokesman for both the Arts and Crafts movement and the Socialist League. Wilde called him “a master of all exquisite design and of all spiritual vision” and credited him with “giv[ing] to our individualized romantic movement the social idea and the social factor also.”

Morris believed that this melding of art and labor, and the aestheticization of daily life, was neither a utopian dream nor a dilettante’s trifle but an urgent social necessity, with radical implications.

Morris’s vision of socialism was “a condition of society in which there should be neither rich nor poor, neither master nor master’s man, neither idle nor overworked, neither brain-sick brain workers, nor heart-sick hand workers.” Instead, he foretold, “all men would be living in equality of condition, and would manage their affairs unwastefully, and with the full consciousness that harm to one would mean harm to all—the realization at last of the meaning of the word COMMONWEALTH.”

Wilde and Morris met in 1881. Morris was initially less than impressed with the younger poet, writing in a letter that though Wilde was “certainly clever” he remained nevertheless “an ass.” Despite the inauspicious start, the two men soon became friends. Their ideas grew enough alike that ten years later, in 1891, Morris’s essay “The Socialist Ideal” appeared together in a pamphlet with Wilde’s “Soul of Man under Socialism.” In his essay, Wilde protested the effect of coercion on the worker, his labor, and the eventual product: “An individual who has to make things for the use of others, and with reference to their wants and their wishes, does not work with interest and consequently cannot put into his work what is best in him.” In the same pamphlet, Morris argued that “instead of looking upon art as a luxury incidental to a certain privileged position, the Socialist claims art as a necessity of human life which society has no right to withhold from any one of its citizens.” Therefore, once socialism is established, “people shall have every opportunity of taking to the work which each is best fitted for; not only that there may be the least possible waste of his effort but also that that effort may be experienced pleasurably. For . . . the pleasurable exercise of our energies is at once the source of all art and the cause of all happiness; that is to say, it is the end of life.”

What is important and valuable, for Wilde as for Morris, is the creative aspect of work, not the strictly productive element or the constitutive effect on the moral character of the individual worker. Both men valued labor in the service of life, not toil for toil’s sake. On this point, the socialists were at odds with both the moralists and the sentimentalists. As Wilde wrote in “The Soul of Man under Socialism,” “A great deal of nonsense is being written and talked nowadays about the dignity of manual labour. There is nothing necessarily dignified about manual labour at all, and most of it is absolutely degrading. It is morally and mentally injurious to man to do anything in which he does not find pleasure, and many forms of labour are quite pleasureless activities, and should be regarded as such.”

By way of example he pointed to a common occupation among the very poor, including sometimes children: that of waiting at street corners with a broom in hand and, as respectable people approached to cross, with their polished shoes and their long skirts, walking ahead of them in the lanes and brushing out of their path the collected dirt, trash, and horse manure, in hopes that they might spare a few pennies in gratitude. Wilde comments, sensibly: “To sweep a slushy crossing for eight hours on a day when the east wind is blowing is a disgusting occupation. To sweep it with mental, moral, or physical dignity seems to me impossible. To sweep it with joy would be appalling. Man is made for something better than disturbing dirt.”

Morris likewise held that “no work which cannot be done without pleasure in the doing is worth doing.” As he explained elsewhere, “If a man has work to do which he despises, which does not satisfy his natural and rightful desire for pleasure, the greater part of his life must pass unhappily and without self-respect.” Such joyless drudgery, economically exploitative and morally degrading, can be contrasted with what Morris termed “real art,” defined as “the expression by man of his pleasure in labour. I do not believe he can be happy in his labour without expressing that happiness; and especially is this so when he is at work at anything in which he especially excels.” Morris believed that this melding of art and labor, and the aestheticization of daily life, was neither a utopian dream nor a dilettante’s trifle but an urgent social necessity, with radical implications: “The beginning of Social Revolution must be the foundation of the rebuilding of the Art of the People, that is to say: of the Pleasure of Life.”

__________________________________

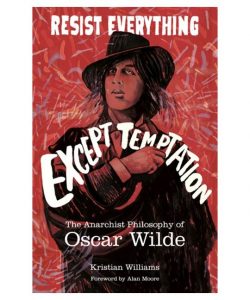

From Resist Everything Except Temptation by Kristian Williams. Used with the permission of AK Press. Copyright © 2020 by Kristian Williams.

Kristian Williams

Kristian Williams is the author of Our Enemies in Blue: Police and Power in America, American Methods: Torture and the Logic of Domination, and co-editor of Life During Wartime: Resisting Counterinsurgency.