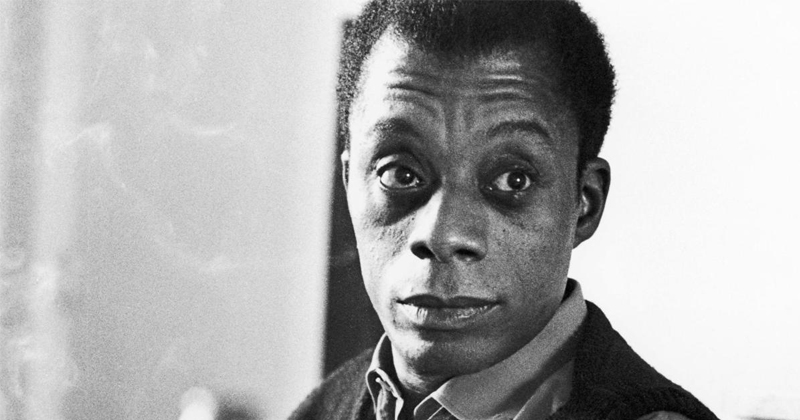

The Many Lessons from James Baldwin's Another Country

Carole Burns Rediscovers a Masterclass in Craft

From the first page, I am immersed in the world of James Baldwin’s Another Country.

It is Rufus’s world from the start. Rufus is a flawed character if there ever was one – and yet how deeply sympathetic I feel as he trudges the streets of New York City. Baldwin’s New York is always vivid and complicated and laden with a character’s history as well as its own. In the novel’s opening pages, Rufus revisits his past: The Avenue, the name Baldwin seems to use for every avenue in New York; the jazz bar where, only seven months earlier, Rufus was playing drums instead of looking in as a vagrant. He hopes and fears people inside will recognize him.

I am revisiting these haunts, too, because I am reading Another Country for the second time, some thirty years after my first journey through its pages. As I do, I am struck by how the novel goes against many of the fictional strategies so often adopted in our commercially driven, MFA-centered literary world. Characters in Baldwin – with the assistance of the author’s incisive thinking – analyze the state of their own being with precision and perceptiveness that most people don’t have. (Baldwin makes a compelling case for telling, not simply showing.) I get lost in flashbacks within flashbacks that are, by today’s sensibilities, brought in before we’re grounded in the present of the story. We’re only with Rufus for five pages before Baldwin plunges us into a flashback that lasts thirty-two pages, and includes its own flashbacks.

Reading Another Country, I wonder if our current obsession with perfection of craft takes our focus away from the story itself. “Intensify!” I remember a creative writing professor, Robert Towers, saying in workshop, and I’m not sure I knew, then, what he meant. I read Baldwin and I can feel what Robert Towers meant. There is an intensity to the scenes and language and emotions and, behind all that, an intensity in the writer himself, which creates the story’s power.

*

I first read Another Country when I was an MFA student at Columbia, in Darryl Pinckney’s class on African American literature. I’ve done a lot of reading and writing, and thinking about reading and writing, in the decades since and, having finished the book again, I can see why Another Country stayed with me.

We’re coy, these days, in fiction, inculcated as we are in Show, Don’t Tell. Every writer shows and tells, yet as a teacher of writing, I understand how that maxim came about when I see early writing by students that is all information, no magic.

But I also think that, as writers, we’re fearful – of being sentimental; of being obvious; of our writing being viewed, if we state an idea simply, as simplistic.

There is nothing simplistic about Baldwin’s straight-forward simplicity. Everything in Baldwin is complex.

Take Rufus, for instance. His abuse of Leona is not excused, it is not rationalized; it is depicted with complexity.

There’s also something both bold and leisurely about how he lets characters think. They mull things over. Vivaldo spends a good fifteen pages just thinking about the past in the lead-up to his seeing Ida on the day they will begin their love affair. In doing this, Baldwin breaks another current creative writing rule: his character is alone in his room thinking. (Today, we must give our characters lights, cameras, action!)

It’s exactly that kind of thinking on the page that I love seeing Baldwin do, and this is perhaps something he’s taken from his non-fiction (essay as a “mode of thinking and being,” to use Philip Lopate’s words). He figures out what he thinks, in essays such as “Down at the Cross” and “Notes of a Native Son”, on the page: moving around his ideas, pressing to the left of them, to the right, moving through to another nuance, a new point – and his characters do this, too.

“Length is weight in fiction,” the writer Joan Silber says in her book-length essay, The Art of Time in Fiction – in other words, writers give more words and pages to moments they feel are important. Do we really want to spend less time in characters’ thoughts? If so, does that mean we think their thoughts are not important? So much – too much, perhaps – of our ideas about story these days comes from film, and yet, thinking on the page is something film can’t do. In writing, we get to think with words. Why not give words the time they deserve?

It’s also counter to this advice I once received from a writing instructor: It’s good to allow your characters to be a little dumb. I hear myself repeating this advice in workshops, as a young writer tries to show how she well she understands her characters by clunkily embedding those abstract ideas into their interior dialogue.

Baldwin allows his characters to be smart: self-aware. On Eric’s last night in France with his lover, Yves, he thinks about the men who’d been casual, sometimes paying, lovers, before he travels back to New York:

“And he thought of these men, that ignorant army. They were husbands, they were fathers, gangsters, football players, rovers; and they were everywhere. Or they were, in any case, in all of the places he had been assured they could not be found and the need they brought to him was one they scarcely knew they had, which they spent their lives denying, which overtook and drugged them, making their limbs as heavy and those of sleepers or drowning bathers, and which could only be satisfied in the shameful, the punishing dark, and quickly…they came, this army, not out of joy but out of poverty, and in the most tremendous ignorance. And there was more to it than that…”

Yes, there is more to it than that. Baldwin doesn’t let form block him from exploring every “more to it” that is vital to explore.

*

A writing maxim that his fiction follows: Baldwin’s dialogue is terrific – it conveys character, it pushes story ahead, it is never mundane.

He also gives himself the luxury of italics to emphasise where a character’s stress would fall. I say “luxury” because I don’t see many writers doing this in dialogue. We’re expected, I think, to get the stresses naturally into the rhythm of a sentence. But the whole point of italicizing these words is that people don’t always stress the expected word when they speak. (I was just watching a film with William Hurt, and I was struck by the unusual cadences of his dialogue – like Frank Sinatra’s phrasing.)

There is nothing simplistic about Baldwin’s straight-forward simplicity. Everything in Baldwin is complex.

Baldwin’s stresses add nuance to meaning. He’s letting us know what his character would emphasize, and also, what his characters – and he – are actually saying. What they mean. And clarity of meaning, as well as complexity, is one of the things I read Baldwin for.

*

I love thinking about the many meanings of the phrase “another country” in Baldwin’s novel.

First, another person is another country. In the beautiful scene when Vivaldo and Ida first sleep together, he watches Ida’s face and knows she’ll resist “any attempt on his part to strike deeper into that incredible country in which, like the princess of fairy tales, sealed in a high tower and guarded by beasts, bewitched and exiled, she paced her secret round of secret days.”

The title is literal, too. The character Eric, like Baldwin himself, left America for France; and Cass suggests this to Ida (“there are other countries”) as a solution to her struggles with Vivaldo.

But Eric also builds another country with his lover Yves, where both are allowed to love and be loved. This is a country that, midway through the book, Vivaldo feels he hasn’t found yet, thinking: “Love was a country he knew nothing about.” I’d like to think that Ida and Vivaldo find that country as the book ends – that the title of the book is a place they reach.

*

My own novel, not coincidentally, is titled The Same Country. As I wrote about racism in America today, I devoured Baldwin’s essays, purchasing the black, silky-paged Library of America Collected Essays, reading them in random order though I probably should have read them chronologically. I read If Beale Street Could Talk and Giovanni’s Room, but I didn’t dare re-read Another Country until my own novel was entirely finished. I don’t know why, really. I wasn’t stealing anything from Another Country, or Baldwin, except for everything he could teach me about life, about being human. And I certainly wanted an echo of Baldwin’s title in mine – as a tribute, and also as a hope that my book might play, in even the faintest way, with what Baldwin meant by “another country”; might tease out the idea that all these other countries are in the same country. We’re in this together.

When I think again about how Another Country opens with Rufus, what comes to mind is the first meaning of the phrase: a person as another country. Is it any surprise, then, that Baldwin engulfed us in Rufus’s experiences, flooded us with this man’s memories and hopes and rage and bitterness and mistakes and losses and loves? We needed to know all of him, or as much as Baldwin could fit on the page, before moving on to Ida and Vivaldo and Eric and Cass. We should feel overwhelmed. We should feel a bit lost.

Baldwin knew exactly what he was doing.

Carole Burns

Carole Burns’s debut novel, The Same Country, is published in the UK by the London-based Legend Press. She was the winner of Ploughshares’ John C. Zacharis Award for her story collection, The Missing Woman. A reviewer for the Washington Post, she regularly interviews writers; her book, Off the Page: Writers Talk About Beginnings, Endings, and Everything in Between, published by W.W. Norton, was based on interviews with forty-three writers including Jhumpa Lahiri and Anthony Doerr. An American now living in Wales, she is an Associate Professor in English teaching Creative Writing at the University of Southampton.