The Manhattan Well Mystery: On America’s First Media Circus Around a Murder Case

Sam Roberts Explores the Death of Elma Sands

On Monday, December 23, 1799, the morning after Elma Sands disappeared, the death of George Washington dominated New York newspapers. Muffled church bells tolled continuously for an hour beginning at noon, as they would each day up to the former president’s ceremonial funeral in Manhattan a week later. To memorialize the general who liberated New York from the British on Evacuation Day in 1783 and was inaugurated in the city as the nascent nation’s first president six years later, marchers accompanied a symbolic three-foot-tall urn to a service at St. Paul’s Chapel on Broadway, where Washington had worshipped after he was sworn in. “Every kind of business ceased, and every thought was employed in preparation for the melancholy solemnity,” according to one account. But by the following Monday, after it was reported that Washington had been buried at Mount Vernon, New Yorkers were already turning their thoughts to somebody else. Elma Sands was still missing.

Born as Gulielma Elmore Sands, she apparently came to New York City from the Connecticut Valley. Everyone knew her as Elma. The vivacious twenty-two-year-old had boarded since the previous July in a house on Greenwich Street owned by her married cousin, Catherine Ring, and her cousin’s husband, Elias. On Sunday night, December 22, Elma mysteriously vanished. Witnesses heard her in her room upstairs.

Supposedly she was preparing to elope. Her presumptive fiancé, fellow boarder Levi Weeks, was waiting in the sitting room, possibly with his brother, then stepped into the entryway. A whispered conversation was overheard. The front door opened and closed. A moment later a friend encountered Sands by chance on Greenwich Street, but her companion, whom the friend could not identify, pulled her away. As far as anyone knows, Elma Sands was never seen alive again.

Burr had already persuaded city officials that by providing water through a private company, he would save New Yorkers money and spare politicians from being blamed for higher taxes to pay for the pumps, pipes, and other paraphernalia that a municipal water works would require.

Winter had only officially arrived the day before, but the season already had been lustily heralded: snow coated the narrow streets and blanketed the spacious and sparsely populated Lispenard’s Meadows, part of the old Anneke Jans farm between New York City and the village of Greenwich, where Elma Sands and her companion appeared to have been heading. The night was frigid, so bone-chilling that she had borrowed a fur muff from a neighbor before she left the house on Greenwich Street. Searchers dragged the Hudson River for her body but came up empty-handed. Two days later her muff was found about half a mile inland, near the fresh tracks of a one-horse sleigh and not far from a well recently commissioned by the Manhattan Company and built with lumber and other building supplies purchased from Levi Weeks’s brother, Ezra.

Given New York’s exponential growth in population once it became the nation’s capital after the Revolutionary War, guaranteeing a permanent supply of water would have challenged any engineering genius. Assemblyman Aaron Burr was undeterred, though; the obstacles would only marginally affect his primary objective, which was to slake his personal thirst for power and money by priming a metaphoric pump.

The previous spring, Burr had bamboozled (and probably bribed) the state legislature—even enlisting his on-again, off-again nemesis Alexander Hamilton— into chartering the ambiguously titled Manhattan Company to provide the parched city, dependent largely on the befouled Collect Pond just north of the Commons (now City Hall Park), with a sufficient supply of fresh water. Burr had already persuaded city officials that by providing water through a private company, he would save New Yorkers money and spare politicians from being blamed for higher taxes to pay for the pumps, pipes, and other paraphernalia that a municipal water works would require.

What Burr did not reveal, however, was that water was not the liquid asset that ranked highest on his business development agenda. A provision buried in the Manhattan Company’s charter allowed it to invest whatever surplus it accumulated in any potentially profitable venture it pleased, which was Burr’s way of circumventing the Federalists’ monopoly on finance through the Bank of New York. Faster than he could open a spigot, Burr created the Bank of the Manhattan Company, the antecedent (by several incarnations) of Chase Manhattan and what today is JPMorgan Chase.

On November 13, 1799, the Mercantile Advertiser printed a public notice announcing duplicitously that the legislature had incorporated the Manhattan Company “for the purpose, among others, of supplying pure and wholesome water.” The company spared no words when it came to self-promotion. “The directors, impressed with the importance of this trust, determined to lose no time and to spare no expense in carrying into full effect the benevolent design of their incorporation,” the newspaper announcement continued.

But by the late eighteenth century, many downtown wells were already adulterated by uncollected offal, the excrement of horses and free-ranging pigs, and other unregulated industrial pollutants that had seeped downtown from the Collect Pond. Like many early New York names, Collect was a corruption of the Dutch kolck, which meant a small lagoon. By the late eighteenth century, the Collect had become so contaminated by animal carcasses and runoff from tanneries and other chemicals that its other name, the Fresh Water Pond, had long ago been rendered an anachronism. Its western outlet to the Hudson River was south of the village of Greenwich, bordering the marshy Lispenard’s Meadows, where the Manhattan Company, rejecting less polluted but more distant sites, had sunk its new well on a blip called the Sand Hills.

New York City has always had two water priorities: a distribution system vital to firefighting, and a pure and ample supply for human consumption. In 1796, responding to a public request for proposals, Joseph Browne, a medical doctor and engineer, ambitiously urged the Common Council to create a private company that would deliver water to Lower Manhattan from the Bronx River. The council embraced the end, but not the means.

Early in 1799, the request was referred to a committee composed of the thirteen state assemblymen representing the city. The panel was chaired by Joseph Browne’s brother-in-law, Aaron Burr. Assemblyman Burr first enlisted Hamilton and the city’s leading merchants to persuade the Common Council to admit the possibility of private ownership, since it would spare the taxpayers and accelerate a solution to a crisis that had been worsening since a yellow fever outbreak the year before. Then he maneuvered the legislature into rejecting the city’s request to finance a publicly owned water supply. In twenty-four hours and without a hearing, he engineered the assembly’s approval of a bill that could not have been described more salubriously: “An act for supplying the city of New-York with pure and wholesome water.”

Going well beyond the public-private partnership that Hamilton had envisioned, the legislated charter empowered the new entity “to employ all such surplus capital as may belong or accrue to the said company in the purchase of public or other stock, or in any monied transactions or operations not inconsistent with the constitution and laws of this state or of the United States, for the sole benefit of the said company.” Hamilton saw through the subterfuge, but too late. Explaining his opposition to Burr’s presidential candidacy in 1800, Hamilton would write James A. Bayard, a Federalist congressman from Delaware: “He has lately by a trick established a Bank, a perfect monster in its principle; but a very convenient instrument of profit & influence.”

To produce a surplus, the company had to spend less money on what was supposedly its principal mission. A panel of three Manhattan Company directors immediately concluded that the Bronx River proposal was, after all, impractical because of insufficient gravity to drive the flow downtown and the likelihood that open canals would freeze in winter. Shortly after its authorizing legislation was approved early in 1799, the directors advertised for suggestions on what any sanitarian would have considered a virtual impossibility: where in Lower Manhattan to sink a well that would yield the city’s households and commercial establishments some three hundred thousand gallons a day of potable water from the Collect Pond.

The charge set off what would become the nation’s first media circus over a murder case, as well as its first transcribed murder trial.

Among those who responded were none other than Dr. Joseph Browne. Reversing himself, Browne now argued that “it is not impossible that the water taken from the vicinity of the Collect, after it has been renewed by a constant pumping, for a few months, might be thought sufficiently pure for culinary purposes.” Browne was hired by the Manhattan Company as water superintendent and elected to the board of directors. The first bid received in response to the company’s advertisement came from Elias Ring, the Greenwich Street boardinghouse owner and dry goods merchant, who had shown no previous passion for hydrology other than having once patented a waterwheel. Elias Ring’s bid was rejected, but before the end of the year, he would be indelibly linked to the Manhattan Company’s well for another reason altogether.

Ring’s dry goods store shared the ground floor of 208 Greenwich Street with a booming millinery shop run by his wife, Catherine, the daughter of David Sands, a prominent minister from Cornwall in the Hudson Valley’s Orange County. (Sands Point, Long Island, was named for the same Sands family; George Washington would have slept in the Sands home in Cornwall on his way to his Newburgh headquarters, had he not left early after his officers suspected a kidnap plot.) Above the shops on Greenwich Street was the boardinghouse where Catherine’s cousin Elma lived.

The Rings were practicing Quakers; Elma was not.

Elma Sands had been missing for ten days when, on January 2, 1800, her body was discovered at the bottom of the Manhattan Company’s well, half a mile from the Rings’s boardinghouse. She was bruised; her dress was torn. But the evidence was inconclusive: Had she jumped, fallen, or been pushed? While the January 4, 1800, New York Daily Advertiser was still crammed with dispatches about the nation’s official and informal displays of mourning for George Washington, the editors found space to report on the “somewhat singular” circumstances of what was still being described as a missing persons case involving a young woman who left with her lover “with an intention of going to be married” and had not been seen since.

On January 6, a grand jury concluded that Sands had been deliberately killed. She was laid out in the parlor of the boardinghouse at 208 Greenwich, a common Quaker ritual, above the millinery shop where she had worked. Very little else was reported about Elma except that she might have been the daughter of an unwed mother, Mary Sands, whose father was from Charleston, South Carolina. To accommodate the crowds that came to pay their respects, Elma’s coffin was carried from the house and displayed outside.

Four days after the grand jury decided on a cause of death, Elma’s lover and rumored fiancé Levi Weeks, a twenty-three-year-old carpenter (described as a laborer in the indictment) of previously unblemished morals, was charged with her murder. He was apparently released on bail, as the record shows that he was rearrested on the eve of his March 31, 1800, court appearance. The charge set off what would become the nation’s first media circus over a murder case, as well as its first transcribed murder trial. By then, though, Levi Weeks had already been convicted in the court of public opinion.

“Elma’s body and the well in which it had been found served as twin omens for the rapidly expanding city,” Angele Serratore wrote in the Paris Review in 2014. “If beauty like hers—vibrant, hopeful, alive—could be mangled by the brute ugliness of murder, what beauty was safe?” New Yorkers must have been relieved when Weeks was arrested. If he were found guilty, they wouldn’t have to imagine that Elma Sands was murdered indiscriminately, the random victim of highwaymen on a frigid winter night, beneath a waning moon too slim to illuminate the snow-covered Lispenard’s Meadows for any eyewitnesses.

__________________________________

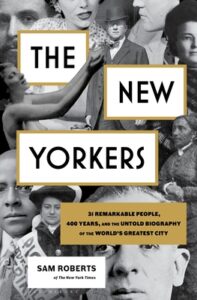

Excerpted from The New Yorkers by Sam Roberts. Copyright © 2022. Reprinted with permission of Bloomsbury Publishing.

Sam Roberts

Sam Roberts, a 50-year veteran of New York journalism, is an obituaries reporter and formerly the Urban Affairs correspondent at the New York Times. He hosts the New York Times "Close Up," which he inaugurated in 1992, and the podcasts "Only in New York," anthologized in a book of the same name, and "The Caucus." He is the author of A History of New York in 27 Buildings, A History of New York in 101 Objects, and Grand Central: How a Train Station Transformed America, among others. He has written for the New York Times Magazine, the New Republic, New York, Vanity Fair, and Foreign Affairs. A history adviser to Federal Hall, he lives in New York with his wife and two sons.