The Man Who Put Premature Babies in Carnival Sideshows

Martin Couney May Not Have Had Medical Credentials, But He Saved Thousands

New York, 1917

The men had shipped out to fight in the Great War. Some of Martin Couney’s earliest patients were among them; one would earn the Croix de Guerre. Back home, however, the littlest citizens were in “no-man’s land.”

It wasn’t just that the country was focused on the war. The entire approach to birth was in transition. With obstetrics becoming a more sophisticated specialty, middle class American women were increasingly giving birth in hospitals instead of staying home. But obstetricians didn’t have much time or inclination to fuss over “weaklings,” as preemies were called, and the nascent field of pediatrics hadn’t quite gotten to them. They fell between the cracks, where they died.

*

All the world loves a baby! On Coney Island and in Atlantic City, Martin’s patients thrived and so did his business. Women, in particular, kept coming back for a feel-good dose of clinical-grade cuteness. One woman would end up visiting the Coney Island concession every week of the summer for 36 years.

Slowly, Martin and his wife, Maye, began filling their home with the trappings of wealth, in keeping with the neighbors. Crystal goblets on the table, prisms of light from the chandelier. Sterling silver chargers under each fine china setting. A servant in the kitchen (live-in), and a chauffeur for the automobile (a matter of safety: Martin did his best, but he was known to be a menace at the wheel). Diamonds for her, black poodles for him.

Martin polished his spiel. He liked to cite the names of famous men who’d entered the world too early:

Sir Isaac Newton

Francois Marie Voltaire

Jean Jacques Rousseau

Napoleon Bonaparte

Victor Marie Hugo

Charles Darwin

And who would know the difference if, in spiffing things up, he burnished his credentials? If he said he’d studied in Paris with the great Pierre Budin, it would cause the city’s doctors to take him more seriously. If he claimed he had European degrees, if he said he’d shown the machines in Berlin and that he’d invented them—well, who was getting hurt? The way the world was, there was nobody checking. Not a soul to contradict him. The truth was, the care the babies got was every bit as good as it would have been if all those credentials were real, and better than any hospital. (One doctor, writing in the Journal of the American Medical Association the previous year, announced that “incubators are passé,” and “It is a fact that practically all prematures entrusted to institution care die.”)

But Martin was starting to paint himself into a corner, albeit a well-appointed one. With the culture changing, he must have felt he needed the credentials—yet anyone believing they were genuine might judge him more harshly. If he had truly been the protégé of Pierre Budin, if he were educated, as he claimed, in Liepzig and Berlin, then it would certainly seem self-serving and exploitative to persist in showing babies on the midway. Why not—at the least—publish clinical results?

Martin Couney had no other recourse. To an extent, like almost anyone of a certain age, he had worn himself into a groove. Too, his wife, Maye, and his head nurse, Madame Louise Recht, had devoted the better part of their lives to this. And money is addictive. But the bottom line was this: He had the means to save thousands of babies, who otherwise were doomed. If he quit, they would die.

What he was offering wasn’t only treatment; it was public propaganda on behalf of preemies.

Propaganda mattered in a war. Later, he could have added Sir Winston Churchill to his spiel.

*

In Chicago, someone else was making propaganda, only his was deadly. Harry J. Haiselden, M.D., was the head of the city’s German-American Hospital. Up until now, the public had seen two prongs of eugenics. One, at least in theory, was “positive”— it focused mostly on the prevention of birth defects, and prenatal and baby care. The second, negative, prong was the elimination of “undesirable” births. Before it was over, the horrors of involuntary sterilization would be visited on 60,000 people in 27 states, including African Americans, Native Americans, Mexicans, people who’d committed petty crimes, and individuals with disabilities or mental illness. American eugenics would influence the Nazis, who admired it. Not content to stop at selectively preventing birth, several American eugenics leaders raised the possibility of killing certain newborns. Dr. Harry Haiselden unveiled the third prong of the trident, denying lifesaving treatment to infants he deemed “defective,” deliberately watching them die even when they could have lived. In some cases, the traumatized parents were in agreement; in others, he had to persuade them that their children were better off dead. He wasn’t the first or only doctor to intentionally allow a child to die, but he was the first to the call the press. He eagerly displayed dying babies to journalists, in addition to writing his own articles for the Chicago American.

Doctors all over the country lined up on both sides of this fight, as did prominent Americans. Helen Keller, the first blind and deaf person to earn a college degree, famously advocated for the disabled, yet she agreed with Dr. Haiselden. In Chicago, attempts to prosecute him and revoke his license failed. The Chicago Medical Society would finally succeed in stripping him of membership, not for letting his patients die but for publicizing his cases.

Meanwhile, frightened parents were writing to Dr. Haiselden, begging him to do something about their very disabled children. They had almost nowhere to turn for help, and now they had been convinced their sons and daughters were dragging down the human race.

*

The movie was called “The Black Stork.” Released in 1917, it starred Dr. Haiselden, coolly playing himself, in a story loosely based on a real case. In the silent, captioned film, the newborn is afflicted with an unidentified genetic disease. His mother is upset—to be expected—but she accepts the doctor’s wisdom following a vision of her child’s miserable future on this earth: a life of insanity and crime. When a nurse tries to hand the doctor his operating apron, he sternly refuses her. Chastened, she turns and walks way, leaving the infant to die alone on a table. The dead child eventually levitates into the arms of Jesus. One 1917 newspaper advertisement read “Kill Defectives, Save the Nation, and See ‘The Black Stork.’”

Later retitled “Are you Fit to Marry?” the movie played in theaters for years.

*

The obstetricians sending babies to a sideshow felt uneasy with the spectacle. The parents, too, had their reservations. But what else could they do? In New York, as the years went by, newborns would be coming from Midwood, Zion, Bellevue, Boro Park Maternity Hospital, Long Island College Hospital, King’s County Hospital, and other Brooklyn, Queens, and Manhattan institutions. Over in Jersey, they were arriving from Atlantic City Hospital, as well as the private homes where they’d been born.

Martin Couney’s patients didn’t have severe anomalies; they were simply early, underdeveloped. But the cultural undercurrent was clear—anyone imperfect, anyone who might grow up with an impairment, wasn’t worth saving.

*

The fire began with a cigarette. Midways were notorious for burning, and in August of 1917, a Luna Park ride called the toboggan burst into flames, next door to the incubators. The head nurse, Louise Recht, with another nurse and a couple of cops, carried all 11 babies to safety.

The incubator show went on: It reopened in nearby Steeplechase Park. And Luna Park survived. Before his career ended, Martin Couney would return. As things played out, the flames of hell might not have sufficed to keep him away.

__________________________________

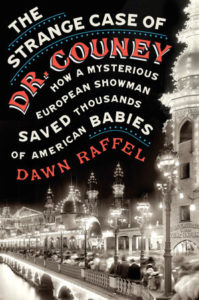

From The Strange Case of Dr. Couney. Used with permission of Blue Rider Press. Copyright © 2018 by Dawn Raffel.