It had been Marina’s idea. Keep Alexei Afanasievich from finding out about the changes in the outside world. Keep him in the same sunny yet frozen time when the unexpected stroke had cut him down. “Mama, his heart!” Marina had pleaded, having grasped instantly that, no matter how burdensome this recumbent body might be, it consumed far less than it contributed. Initially, clear-eyed Marina may have been moved by more than primitive practicality. There had been a period of infatuation between her and her stepfather, when the little girl would crawl all over Alexei Afanasievich, who seemed as big as a tree to her. She would go through all his pockets and invariably find chocolates planted there for her. Alexei Afanasievich taught her how to fish and how to toss plywood rings on a post. Once the two of them had cleaned out every last gaudy toy with the digger claw on a Czech grab-n-go.

All that lasted about a year. For a while, the dragonfly pond out back of their brand-new nine-story apartment building had sucked on their two red-and-white fishing floats as if they were pacifiers; by the next summer, the pond had turned into a swamp plastered poison green with plants—and now there were stalls on the spot. Marina couldn’t forget this entirely, at least not until that rather bizarre moment when, a month after Brezhnev’s television death, she hung a medal-strewn, beetle-browed portrait of that official paragon on the wall.

In retrospect, Nina Alexandrovna could only wonder at young Marina’s perspicacity. You’d think she had nothing on her mind beyond Seryozha and her synopses. Yet, at the first historic tremor, she had divined in the decrepit general secretary’s replacement by a younger, more energetic one not a pledge of Soviet life’s continuity but the beginning of the end. She immediately began preserving the substance of the era for future use and purging it of any new admixtures, no matter how harmless they seemed at first.

So it came to pass that their good old Horizon television—on which only impressionistic bursts of static were still in color—showed the farewell to that great figure of the modern day (the richly beflowered tomb, wreaths made to look like medals, the craned neck and half-face of a watchful man lined up to view the body)—and then went stone dead. Marina temporarily forbade anyone to buy another, but she did take out a subscription to Pravda.

No one could say for certain whether Alexei Afanasievich could read now. He had always carefully worked his way through the newspapers, holding his place with a school ruler, as if measuring the quantity of information by the millimeter, but now he looked at the newspaper page that Nina Alexandrovna held at half-mast without moving his eyes at all. It might as well have been a bedsheet she’d picked up to mend. Nina Alexandrovna was charged with reading the paralyzed man specific articles, which Marina made fat deletions in and supplied with handwritten insertions.

Nina Alexandrovna carried out these instructions, although she was embarrassed by both the articles and her own voice. She had to tilt the newspaper very slightly to find the end of Marina’s almost indecipherable sentence—and sensed vaguely that Alexei Afanasievich’s immured brain, with its dark bruise from the stroke, was sending her staticky, buzzing bleeps in reply. Every once in a while she imagined (she couldn’t bring herself to verify this) that if she just leaned closer to this desiccated head with the crookedly stretched mask where his face used to be she would be able to talk to Alexei Afanasievich without using any words at all.

Very quickly, outside time became so altered that there wasn’t even anything in Pravda for Marina’s pen to rework. By the time they started knocking out windows in the stuffy Soviet rooms (overnight, the still relatively young and full-cheeked Apofeozov went from being first secretary of the Party district committee to being a democratic leader who had publicly torn up his Party card), inside time had come to a standstill, and this was the time maintained in Alexei Afanasievich’s room, which had a faint smell all its own that lacked an objective source, like the acrid trace of a burned match.

Everything in the room manifested a tendency to stand still, to doze off in an uncomfortable position. Nina Alexandrovna would catch this special quality of autonomous time, at the boundary between wake- fulness and sleep, when suddenly she merged with her surroundings and felt nothing but her own weight—which was bliss, but spoke to Nina Alexandrovna of her weariness even more than an attack of hypertension could. In the afternoons she noted how good it felt to hold the weight of most objects in the room.

Something suggested to Nina Alexandrovna that this stopped time knew no essential difference between order and disorder. She couldn’t help but see that things in the room would accumulate and then shed their ordinary meaning. This loss of meaning was especially obvious while she was cleaning. Nina Alexandrovna battled resolutely against the thick and amazingly even dust that eagerly settled on a wet spot where tea had spilled, quickly becoming a fuzzy patch. She was endlessly wiping and feeling everything like a blind woman, whether she needed to or not.

Privately, Evgenia Markovna, the doctor who came to check on the patient, must have wondered at the sterile chaos maintained around the sick man. The china figurines on the sideboard looked like products of Nina Alexandrovna’s housecleaning, shiny knickknacks sculpted by hand and rag. Here, too, were crowded empty prescription bottles that should have been tossed long ago, also freshly wiped and clear right down to the medicinal tear at the bottom. The glassed-over Brezhnev portrait, which the doctor never examined but always turned to look at as she left the room, also bore the rag’s traces: a violet rainbow from cheap window cleaner. Each time as she finished with the portrait, Nina Alexandrovna would cautiously lower her bared leg with the swollen tendons to the floor and climb down from the wobbly chair in two moves, and Alexei Afanasievich would shut his big right and small left eye in approval, as if he were seeing precisely what he thought he should see.

Klimov the skeptic, who had opposed the entire scheme (at the time he hadn’t yet lost all his rights and had tearfully defended him- self against his mother-in-law’s slightest digs), remarked more than once that if they wanted to retain the atmosphere of the seventies, then they should hang a portrait of Vysotsky, but Marina, guided by instinct, ignored her husband’s advice. There was something false, of course, alien, even, about this particular portrait of Brezhnev. As Seryozha, who was busy with his then wildly lucrative (despite the sewer smells) video store at the train station, said, “It’s a prop right out of a Hollywood movie about Soviet life.” Yet this encapsulated time, which had survived its own violent demise in this one individual room, obviously possessed properties no one had ever observed in its natural state.

These properties had something to do with immortality. The general secretary’s rejuvenated photo—half documentary print and half retouched and clearly made during his lifetime—was striking for that very quasi-drawnness you see only in a dead person’s features. So precise was this impression that, when she realized exactly what the impotent fold of Brezhnev’s mouth and the sepulchral tidiness of the hatched-in hair reminded her of, Nina Alexandrovna began wiping the portrait with anxious deference and avoided turning it over and seeing the half-erased inventory number on the back.

But what was amazing was this: the general secretary, whose death had here been reversed and whose longevity had become a natural feature that only kept increasing, had somehow borrowed an authenticity from Alexei Afanasievich that Brezhnev himself had never possessed. If Brezhnev had been a cardboard figure in whose name books were written and on whom mutually exclusive medals had been hung, like a game of tic-tac-toe, then now there was no reason to question his existence, if only because the general secretary could no longer die—even if he were to admit his desire to do so.

Also a veteran of the Great Patriotic War, he was now, in outside time, not dead but missing in action. Having effectively distanced himself from those veterans with schoolboy faces ruined by drink who shuffled along behind their new Communist leaders and continued to live in the present day, he had attached himself and even begun to bear a certain iconic resemblance to Alexei Afanasievich, who had never belonged to the Party. Anyone entering the room (though in fact they let in almost no outsiders) could see the paralyzed man’s forehead, as worn as a coin, and the two needly, low-hanging eyebrows—and see the same thing on the cheap wallpaper covered with teacup flowers. Even Nina Alexandrovna somehow succumbed to the reassuring illusion that Brezhnev in his official portrait was not the former head of the Soviet state at all but simply a distant relative.

Naturally, as the project’s author, Marina had to decide whether this spectral time had any need of events. She had outlawed the principal natural event (death), thus rendering any event related to it (illness, injury, leadership changes, and so forth) impossible—and any attempt to add to this list made even the decisive (she had decided so much!) Marina uneasy. One got the feeling that the list permeated life so deeply that it might eventually include anything, even something no one had ever connected with death—as if, at the slightest attempt to pull out the plant, the roots would suddenly pull hard sideways and down and lift a little, like a seine loaded with every kind of dirt that ever comes under men’s feet.

One way or another, Marina prohibited anything that might arouse negative emotions (in this sense, her stagnation had achieved perfection). She cut short any attempts by Nina Alexandrovna to inform the patient of anything personal—about an apartment in the next entryway being robbed, for instance, or Alexei Afanasievich’s nephew poisoning himself with rotgut vodka. “Mama, the money!” Marina would exclaim in an anguished voice, obviously referring to Alexei Afanasievich’s heart but at the same time clutching at her own, the plump heart beating in her chest.

“Daughter, dear, does it hurt?”

“Mama, leave me alone!” Upon receiving this familiar rebuff, Nina Alexandrovna felt on her left side, under her ribs, a subtle ache, which she experienced as a heaviness in her fingertips. Aware that, with the consolidation of inside time, any illness of hers had simply become impossible, though, she took all this back with her to the kitchen. She now pictured Alexei Afanasievich’s heart—which had to be safeguarded as the family’s principal treasure—as a large crimson tuber for which his paralyzed body had become something like a vegetable bed entwined with engorged blue roots.

__________________________________

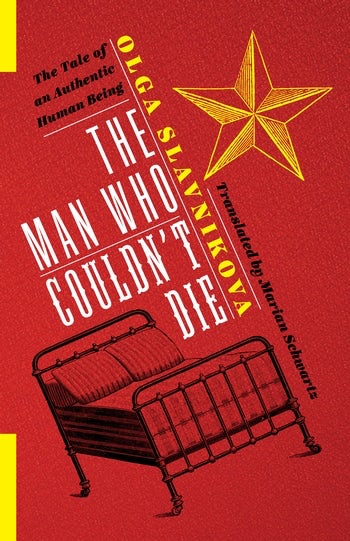

From The Man Who Couldn’t Die. Used with permission of Columbia University Press. Copyright © 2019 by Marian Schwartz.