The Makings of Grace Paley: Writer, Activist, Feminist

Judith Arcana on the Writer's Upbringing, Marriage, Motherhood, and Career

Though Grace Paley never stopped writing, and the publication of her first book demonstrated that she was in fact “a writer,” her energy turned increasingly to political activity after 1960. Her desire to remain outside the literary world was abetted by her interest in the growing peace movement. She was one of the neighborhood people who founded the Greenwich Village Peace Center in 1960-61, and peace work became her political center in this decade. Additionally, in 1965 she began to teach fiction writing to college students, which altered her view of the literary community by urging her further into it—an ironic turn for a nonacademic artist and activist.

In fact, her growing reputation as a writer—which burgeoned in the mid-70s and beyond—was fostered by the extraordinary circumstances of her first book’s being reissued, by two different publishers, in 1968 (Viking Press, hardcover) and 1973 (American Library’s Plume Books imprint, paperback). The more obvious effects of this practically unheard-of situation include the fact that new generations of readers came to know her work, keeping her as current as if she had published new collections; in addition, she began to make a living by her art. A less felicitous result was that she was misunderstood, perhaps even held back in her development. The reading public expected her, as late as 1973, to be the woman—the authorial persona—who had written “A Woman, Young and Old,” when she was actually generating a new conclusion for “Faith in a Tree” and creating “The Long-Distance Runner,” two stories that reveal extensive development of political consciousness in their author.

In that same vein, Grace was disappointed and irritated to find that her book’s subtitle had been inverted and its preposition changed. Her own full title—carried on the original edition—was The Little Disturbances of Man: Stories of Women and Men at Love. The new edition read The Little Disturbances of Man: Stories of Men and Women in Love. Not only was her inversion of the genders ignored, but her prepositional suggestion of the adversarial quality of emotional relationships between women and men, a central theme in almost every story of that volume, was erased. Republication was not an unmixed blessing.

Her next stories, collected for Enormous Changes At the Last Minute in 1974, were all written between—or during—meetings, actions, classes, and readings. By the end of the 50s, the American Friends Service Committee had begun to fund small neighborhood peace groups. Naturally, their first contacts were with those who had political experience, people like Grace and her friends, who had already begun to oppose the proliferation of atomic and nuclear weapons and to educate against militarism. The Quakers’ method was to seed small neighborhood organizations by sharing information, paying the rent on an office for the first six months, and encouraging each group’s autonomy.

The Village Peace Center was such a group, begun largely by PTA members from PS 41. Many people who became Peace Center members in the early sixties were already working on the General Strike for Peace or attending small local meetings on neighborhood issues. These included Mary Perot Nichols and her husband Bob, who would later become Grace’s lover and second husband; Mary and Bob were separated by mid-decade, Jess and Grace shortly afterward. Bob and Grace met in the struggle to close the roadway through the park; he had been very active before she came into the fight as a representative for the third grade of PS 41. (In 1960, Bob Nichols rode in the last private car to drive through Washington Square.) The Nichols and Paley families knew each other and had friends in common, though the three Nichols children—Kerstin, Duncan, and Eliza—were several years younger than Nora and Danny Paley.

Grace Paley railed against the racism and class discrimination inherent in the tracking and grading systems.

Grace says that what she learned in this period from nonnative New Yorkers like Mary and Bob, people who had lived in other cities and in small towns, was that “you can fight city hall”—and win. Bob Nichols concurs, in ironic military metaphor: “We were very successful. Almost every war we waged, we won. All of our local campaigns were successful, with rare exceptions.” This nearly all-win, almost no-loss record, gained in the park and the school, working on neighborhood issues, could not hold in the larger arena of national and international struggles, but it did strengthen Grace and her companions, encouraging them for the larger “campaigns” ahead. That was part of her education; she learned that if small groups of local people take action, they can win. To those who fear such local victories will only make people unrealistic, Grace says that’s not so—“It happened, didn’t it? It was real. We knew that you could do it, if you could just hold on, you could prevail. When you sit down in the park, if you stay there, you can win.” Grace’s personal stubbornness was intensified by what she learned in city and neighborhood politics, which fostered the tenacity necessary for organized resistance.

Other members of the Peace Center soon included Sybil Claiborne, by then a close friend, and Karl Bissinger, who came down from north of Fourteenth Street to join the group. Karl, who also became a personal friend, worked closely with Grace at the Peace Center, and later in the War Resisters League, for over two decades; he says it was at the Peace Center in the early 60s that they all began to understand that the Vietnam War “was really being run from Washington. How innocent we all were!”

Grace remembers that when she began to work in the Village Peace Center in 1960 or 1961, they fought civil defense drills in schools and protested atomic and nuclear bomb testing. “It was totally absorbing. I always had a certain amount of antiwarness in me. That was true even when I was in high school. Even in elementary school.” At the Peace Center they also did “a certain amount” of civil rights work; they tried to work with people in Harlem, an effort which grew out of a home base that also fostered antiracism. Grace was also interested in the city itself, so that her consciousness grew beyond the block, beyond the neighborhood: “I was really interested in what we came to call ‘ecology,’ the whole thing about the parks and the piers and the rivers and the land that was New York, that was Manhattan, that was the islands and the boroughs around it.”

Sybil, who has done political work with Grace for nearly 35 years, says there is a notable difference between the central role her friend played at the beginning of the Peace Center and Grace’s current situation. In the early years, Grace was really “in the middle of” the organizing; she had a lot more to say about what was to be done. Many of the actions and policy decisions that came out of the Peace Center were strongly influenced by Grace, but “over the years,” Sybil observes, “she has stepped to the side.” Now, in similar groups, while she may offer suggestions of a focus for action, she seldom initiates. Sybil assumes that Grace’s new posture is one result of having become “famous”—she doesn’t want to dominate the meeting—as well as the fact that “Grace is a genuine listener, a very careful listener.” She listens well, to learn before she decides whether to speak. “Over the years she has taken more and more of a backseat.”

In 1961, when Grace Paley was one of the new group’s most active members, the Peace Center arranged a sizable demonstration at City Hall to protest the municipal air raid shelter program. Their success led almost directly to frequent actions against US policy in Vietnam. Bob Nichols says the group’s “specialty” was neighborhood vigils; he remembers being out on the street in the snow in front of a City Planning Board meeting and feeling strong support from the community when “people we knew all came by and said hello.” When the war was recognized and its origins more fully understood, as Karl explains, Grace became one of the people (she may have been the originator of the idea) who read aloud the names of the war dead at vigils, urging that US troops be brought home and the draft ended. Throughout the Vietnam War years, she was one of a group that picketed the court house every Saturday or Sunday, carrying signs that read “Not our sons” and “Stop This War.” They never missed a weekend, no matter what the weather was, in eight years.

These demonstrations were part of the growing national movement against the Vietnam War and the draft and demanded a tremendous amount of Grace’s energy and time. Her children, strongly affected by her activities, are truly “children of the 60s” in that they were themselves participants in protests against the war and racism and in the street culture that flourished throughout the period. Like many high school students, they struggled with those elements in their own lives—the inadequacy of the schools, the adolescent drug scene, their parents’ growing disaffection—which replicated massive social upheaval throughout the United States and Western Europe.

The Paley children’s adolescence produced at least one mirror reversal of the conflicts found in the “typical” American family. Most 60s parents despaired of their children’s sudden revolutionary inclination, but Danny Paley says that at the age of 13 or 14 he became very conservative for about a year, “simply because everyone else in my family was so liberal.” He hung up huge pictures of Lyndon Johnson in his room and displayed them in his windows. He says he did it because he knew that “it annoyed everybody. The more it annoyed them the more I put the pictures up.” Furthermore, he “insisted” on visiting the capitol and the White House, as an exercise in citizenship and patriotism.

Despite that brief period as a right-winger manqué, Danny never strayed so far from home that he actually joined the opposition. Grace recalls with pleasure that he always—even in grammar school—loved neighborhood actions, especially when politics came right to the family’s door. Nelson Rockefeller visited PS 41, as did Ed Koch before he became mayor. “And Danny loved that,” Grace says. “He loved the fact that it was right there, next door, on the block, on the street.” During the middle and late 60s, he and his friends were active in antiwar demonstrations, several of which he remembers as “really violent.” Now, though his judgment stands allied with theirs, Danny Paley does not often engage in the political activism of his mother and sister.

Nora thinks she seemed awfully radical to her kid brother, maybe even more radical than their mother. As a child, Nora had had basically the same politics as Grace, but she recalls that “Danny was a little different.” She feels that his stance had more to do with his reaction to her than to his mother, because he was the younger child. Alluding to Danny’s “patriotic period,” she remembers that even in the 50s, he would tease her by saying, “Oh, you just like Castro because he has a beard.” He was near the mark there, Nora laughs: “That was probably true; when I saw someone with a beard I did like them, because they looked familiar to me. Every man in the Village had a beard, and no one anywhere else did.”

Grace did everything she possibly could, but, like her own mother before her, she was confused by a daughter who was thinking with a new kind of mind.

Like her mother and later her brother, Nora Paley rejected high school. “I wasn’t not interested in learning. I was passionately interested in learning.” But unlike Grace, who attributes her “failure” to succeed in high school only to herself, Nora developed a political critique of the school system. Along with many high school students of that time, some of whom organized teach-ins, published independent newspapers and magazines, picketed their schools, demanded changes in curriculum, and dropped out in great numbers, she understood the hypocrisy of the system and was very angry at being “forced to be in a place where we did nothing all day.” She railed against the racism and class discrimination inherent in the tracking and grading systems. “All my friends were Puerto Rican. They were all being put in these vocational classes.” Nora remembers the struggles of her good friends who were not allowed into the college-prep track, even when they asked to be placed there and demonstrated they could do the work.

She feels that Grace, who had always believed in the public school system, “just didn’t know” about the daily reality of the average city high school. Sharing her mother’s perspective in theory, Nora points out that “it isn’t that I wanted to go to a private school; that isn’t what I wanted. I just wanted to not be in a school that was as wrong as those [schools] were.” Indignant about the schools and powerless in her youth, she held her mother responsible: “I was mad at her. I didn’t think she was respecting me. I thought she should have had enough respect for me to let me quit high school and do these amazing things I had in mind. So it was a hard time between us, a very hard time.”

Nora attended three different high schools, with three different ethnic and racial communities, before she finally graduated. The family prevented her from dropping out, which she passionately desired to do. Her disgust and boredom finally led to a total rejection of school. Like Grace at Hunter College, she made no formal statement. But she began to wonder what would happen if she didn’t take midterm exams, or pick up her report card, or even show up for classes. She had never considered any of those possibilities before. When they occurred to her, she realized that the probable consequences of such behavior no longer mattered to her. She and her friends began to cut school, take amphetamines and ride the subway, speeding all day beneath the boroughs of New York City. Resembling the adolescent Grace Goodside of an earlier era, Nora was, she says, in “an extreme mode and an extreme mood.”

She finally attended a school in Brooklyn, where her aunt Jeanne was a guidance counselor, and says that she only graduated because Jeanne “picked me up every day in a car and took me there, which I hated—I really hated.” Actually, her aunt Jeanne was the one who pushed Nora through the school system. Grace thought that because Nora loved her aunt—Jeanne and Nora have always been very close—she enjoyed going to school with her, and Grace knew that those rides ultimately helped to keep her daughter in high school. Since Nora didn’t want to finish school, she naturally had a different view. She says—replicating her mother’s assessment of her grandmother Manya’s anxiety—that Grace simply didn’t know what to do. She was worried about her daughter but didn’t really understand Nora’s situation. Her daughter knows—and knew then—that Grace did everything she possibly could, but, like her own mother before her, she was confused by a daughter who was thinking with a new kind of mind.

“Grace says now that she should have let me drop out of school,” Nora points out, and Grace agrees: “I made a mistake. I should have let her leave school when she wanted to.” The wisdom gained in that crisis with Nora was useful when Danny came to the same conclusion less than two years later; Grace changed her policy and allowed her second child to leave school.

Despite the apparently unique ferment of the times, both of Grace’s children had high school experiences strikingly like their mother’s. They started out as very good students, and then (echoing some of Grace’s exact words), Danny says, “All of a sudden instead of school being important to me, girls became important, and my friends. I really went straight downhill for a number of years.” Danny—more like his sister here than his mother—also recognizes the cultural aspects of his scholastic decline, viewing his shift from books to peers as typical—“like most teenagers”—and seeing the cultural and political upheaval of the time as a source and cause. As Grace would say, he was strongly influenced by the currents of his time and place in history. “I started taking a lot of drugs during that period of time,” Danny says. “Nothing addictive, not heroin or anything, but enough to really kill me in school.” Like Danny’s maternal grandparents, who had been equally in the dark about their daughter, Grace and Jess had no idea what was going on in their boy’s life; he can barely recall their presence during that period. Sooner than his mother, but right in line with his big sister, Danny became disaffected, and “finally I dropped out of high school.” But he too was subject to family pressure and finally graduated from a private school uptown, Robert Louis Stevenson, to which “rich people sent their kids so they could graduate from high school without having to do anything. It was a joke school; a lot of famous people sent their kids there.” He was able to attend Stevenson because both of his parents were finally making some money. Not only was Jess getting a number of good assignments, but Grace had also begun to teach college classes, so the Paleys had at least one steady paycheck coming in.

Among the people who gradually grew more intimate with Grace, and more important in her life, was Bob Nichols.

Like most children, Danny Paley perceived his mother’s increased activism and time spent at her work as his personal loss. “By the time I was a teenager—of course it may have been as much my fault as hers—I felt like she wasn’t always there when I needed her.” Now that he is a father, he views her chosen methods critically, suggesting that she should have been more directive, should have offered him more guidance. “I was doing a lot of stupid things, hanging around with the wrong people, and letting school get away from me. [But] she had a different kind of philosophy than in fact I would have as a [teenager’s] parent. She felt she could trust me, and she wasn’t going to interfere; luckily it worked out all right. (It might not have though, because I had a lot of friends who didn’t even live—you know, who OD’d on drugs or something [else] terrible.)”

At one point, when he was close to danger, his mother’s intervention was dramatic and effective. “I was taking amphetamines in powder form, and somehow my mother became aware of it—I guess it was obvious because I wasn’t sleeping at all. And then she got real angry—it was almost the same anger I had seen with that cop. And it affected me the same way.” She yelled at him. She didn’t mind about his social life, or his grades, or the hours he was keeping, “but,” she declared, “this [taking amphetamines]—if you do this, just don’t even come back here; I just don’t even want to see you.” “I never did it again after that,” he says, “because I knew, when I saw that side of her, just like that cop must have known that day: Don’t do it! And if a cop with a club and a gun knew not to, then I certainly would know not to.”

Nora and Danny Paley’s disinclination to accept the system is striking in terms of their mother’s educational history. When Nora was a teenager she never once considered the resemblance between her own behavior and her mother’s earlier experience. It never occurred to her to make the comparison during that time because Nora, like most adolescent girls, was thinking of Grace as her mother—solely in terms of the maternal role—not as an actual person, a woman who had been a girl, a girl who had once had the same kind of life experiences she was having. Nora now thinks that the fact that she was repeating her mother’s pattern—even if unconsciously—“might have been why I was mad at her. [I probably felt that] she, having had that experience, should have known better, should have understood, should have been able to deal with me and help me.” Like Grace, who had resented the same responses in her own parents, Nora was angry that a mother who professed a radical analysis of society and its institutions would not apply that analysis to her daughter’s life.

While the children were growing up and out in miscellaneous directions, Grace too was changing. Thinking about the so-called empty-nest syndrome, she comments, “In my view, nobody really ever goes away; they’re always coming back—they come back a lot. When I went away with Jess, I didn’t put my family behind me. I wrote letters, they wrote letters, we were in touch. We always had contact. I didn’t take myself away from them.” She points out that when Nora and Danny were leaving home, she was leaving home too. “So it was very complex, very complicated. I was really too busy to worry whether they left or they didn’t leave. And it seems to me that all their lives they keep coming back. So I think it’s a big thing that psychologists just made up.”

Like much of American society, the Paley family rearranged itself through the decade of the 60s. While her personal “neighborhood” enlarged—extending her network of local and family ties— Grace reshaped or created new emotional alliances and connections, some of which provided essential sustenance for years and continue to do so today.

Among the people who gradually grew more intimate with Grace, and more important in her life, was Bob Nichols. Bob was a political ally, working at the Peace Center and taking part in various neighborhood demonstrations. By the mid-60s, around the time Grace began teaching, Bob says that she “more and more did serious work in the basement of the Washington Square Methodist Church,” where the resistance movement and draft counselors had office space. He says he frequently “went on actions and often stopped to hang around and wait for her—or we’d all go out for espresso.” Bob’s and Grace’s lives coincided beyond political commitments. While continuing to practice as a landscape architect, Bob was a member of the Village Poets in the 60s; in addition to writing poetry, he wrote “about twenty” plays that were performed off-off-Broadway or in the streets.

One of his plays, typical of much urban street theater of the time in its community base, was an adaptation of Everyman, in which many neighborhood and Peace Center people took part. Sybil Claiborne remembers that Grace asked her to sew the costumes. As in other towns and cities in the United States in that period, the community not only was engaged in critical analysis of federal and local governments and organized action against their policies, but also was coming together in pleasure—people enjoyed themselves. They brought passion and laughter to their serious business; they made art that was play and play that was streetwise education.

In that atmosphere, Grace Paley and Bob Nichols spent hours and days together—indeed, they worked years together, their camaraderie growing into friendship and love. Bob’s marriage was over by the mid-60s, and he had had liaisons with a few other women before he and Grace became a couple. Her own marriage had been relatively static until the early years of the decade, when the gaps between her and Jess opened painfully.

Though Jess had encouraged her to write stories and was enthusiastic about them when she did, he did not so actively cultivate his own art. This had not mattered in earlier years, when Grace had not yet published, but it may have begun to make some subtle difference after the late 50s, for she had become “a writer,” regularly working at her craft. After 1960, and certainly by 1965, when she had begun to make new friends who were writers and teachers of writing, Jess was no longer in the center of her life. At the same time, as her political involvement increased between 1960 and 1965 and began to take her out of the neighborhood—or to jail—her closest attachments developed among those who shared that experience. Though Jess certainly held a similar world view, would probably have voiced many similar opinions, and must have pulled the same levers in a voting booth as Grace did, he never became an activist.

Additionally—and ironically, given his encouraging influence in her early story writing and his sporadic absences due to assignments out of the city—his frequent presence in the house may have lessened her opportunities to write. Karl Bissinger explains that when Jess wasn’t working on a film, like a husband in early retirement “he would be around a lot. He would start at nine o’clock in the morning, and ask Grace to have cups of coffee with him through the day, and there was no time for her to write. It simply didn’t occur to him that he ought to leave her alone. He was always there. As an artist she had no room to function.”

Grace and Jess’s marriage was subject to the cultural and political circumstances that broke open so many American marriages in the 60s.

When he did work on films, his assignments took him away from his family for long periods. In fact, Jess Paley was on his way to Southeast Asia when Little Disturbances appeared at the booksellers, and he missed the public’s reception of his wife as a writer. He wasn’t there for the excitement of the reviews or the thrill of seeing the book in stores. While Grace didn’t necessarily resent his absence in all the major areas of her life, she regretted it. Regret seems to have been the overriding tone of her slow, difficult separation from Jess Paley. She regretted their lack of mutual interests and activities. She regretted his absences. She regretted that her steadily increasing success as a teacher and writer was occasionally concurrent with hard times in his own work. She regretted his lack of commitment to action for social change.

Like many couples then, the Paleys didn’t break up so much as come apart; they moved in different directions. Or, perhaps more accurately, Grace moved away from where they had been together, and Jess, no matter how much he traveled, stayed there. The Paley divorce, which didn’t actually occur until 1972, was not an unusual one. It produced all the requisite pain and doubt; it included the grief of the children, disillusionment on both sides, disagreement about who would leave the family home, and the complication of at least one new lover.

Grace and Jess’s marriage was subject to the cultural and political circumstances that broke open so many American marriages in the 60s. The Paleys were actually among those most likely to come apart: they had married young, in a period of national stress and uncertainty; the husband had been deeply affected by his war experience, professionally and emotionally dislocated; the wife was eagerly moving beyond the immediate concerns of a traditional wife and mother, and she was changing while her husband’s projects and interests remained static. Moreover, after years of “crummy” part-time jobs, she had finally begun work that would make her financially independent. In previous eras, such women rarely worked for (good) pay, generally suppressed their interests, and arranged themselves around their husband’s and children’s needs and desires. But Grace Paley’s natural obstinacy and determination were explicitly encouraged by a decade of rapid, intense sociopolitical change.

Grace’s own mother had remained—long after necessity, until her death—in a family household that was far removed from her ideal; Grace’s aunt Mira—eventually as bitter as she was beautiful— did the same. Neither woman had acted decisively in her own behalf. Grace defined her mother’s situation in “Mom,” first published in 1975: “Her life is a known closed form.” Beyond the cautionary models of her mother and aunt, we can look to the character of Grace herself. Her friends say that one of the reasons she took so long to leave the marriage is that she doesn’t really believe in divorcing anybody. Jane Cooper, who came to know her just as the separation began, says, “Relationships that have been family to Grace, that have been really close over the years—those she never really lets go. Those people are always her family. So [the separation] must have been not only excruciating for her, but also really really hard to understand; it took a great deal out of her. I think it actually tore her apart, truthfully. But finally she got to the point where it was necessary to separate; there was no question about that.”

Whereas some of Grace’s people found Jess remote and preoccupied, even narcissistic, Grace never seems to have blamed him. Karl Bissinger explains that “Grace is loyal. She’s in it for the long haul. She doesn’t take on anything lightly. My sense of [their relationship] is that there was a whole lot going on” that no one but Grace and Jess would ever know. Karl did feel that he could see Grace was “driven to the point where she decided to call it a day; it was clear that Grace had called it a day.”

Whatever was difficult or painful between Grace and Jess Paley, everyone who knew them understood that the issue was not initially a loss of love. Once Bob Nichols entered the scene, having to choose was all but impossible for Grace. Sybil Claiborne says that in the late 60s, when both men figured prominently in Grace’s life, she probably would have liked to be married to both of them, holding both of them dear as she did. “Wants,” a story Grace wrote at the end of the 60s and published first in 1971, is narrated by a woman who—prompted by an encounter with the man to whom she “had once been married for 27 years”—ponders the kind of romantic and realistic considerations Grace must have weighed in those years: “I wanted to have been married forever to one person, my ex-husband or my present one. Either has enough character for a whole life, which as it turns out is really not such a long time. You couldn’t exhaust either man’s qualities or get under the rock of his reasons in one short life.”

The chasm between Grace and Jess was not the result of her attraction to and growing love for Bob Nichols. Bob could only have moved into a life where there was room for him, and that room had already been provided by the Paleys’ divergence. At first, they did the sort of thing many couples do in such straits: Grace traveled to Europe to join Jess on an assignment in 1966; he photographed her looking beautiful in a gondola on the Grand Canal in Venice. He remembers that one afternoon they discovered a copy of Little Disturbances on a tiny marble table in the hallway of their pension in Florence. Though of course she accused him of planting it there, he still insists he was as astonished as she to find it.

But they continued to grow apart. In the face of increasing intensity in the antiwar movement, one of the major problems between them had to be that, cynical as he was about government policy, Jess still did not choose to take action. Some of their friends and family felt that because he had no apparent substantial political convictions, he resented her expense of energy in that direction and even sometimes doubted the sincerity of her commitment. He often expressed annoyance with her; he complained about feeling neglected. His personal unhappiness and disapproval of her activities constrained Grace. He refused to take part in the life she and her friends lived. He eventually refused to go anywhere with her, her sister recalls, though sometimes Grace would cajole or plead with him to come. Finally she stopped pleading and went, Jeanne says, “on her own.”

In this period she began to be arrested for various forms of civil disobedience. One of the first big actions (which brought out lots of people, garnered good media coverage, and created an impact felt by the authorities) was in that same year of 1966; Grace and Bob were among those who rushed out into the street and sat down under the Armed Forces Day Parade’s rockets and missiles on Fifth Avenue. Carrying daffodils, the demonstrators sat down to register their objection to the celebration of the military and its weapons. Their refusal to allow the parade to continue led to their arrest and removal; that was the first time Bob Nichols and Grace Paley were arrested together. So, in the same year as that romantic sojourn in Italy, Grace was sent to the Women’s House of Detention, causing a separation that was a more appropriate emblem of her relationship with Jess than the gondola ride had been.

Naturally, the children were affected by the antipathy between their parents. Danny remembers his father’s growing anger toward his mother and a general increase of tension in the house, “Until it got to the point where I couldn’t stand to be there anymore—although I was at the age where I didn’t want to be there anyway. Beyond that, it was a kind of drifting apart—it just seemed to happen. The splitting up period lasted a few painful years. I guess it started when I was about 15, and by the time I was 18, they were pretty split up. When they finally did get divorced [in 1972] it was a relief to me, because I thought that was something they certainly needed to do. By that point it was pretty clear.”

Grace was among those who experienced an accelerated rise of consciousness that matched the swift change in the society.

He suggests that “some of it had to do with my mother’s own life taking away a lot of time, probably [time] that my father felt he was losing. She was spending more and more time writing, which was part of the argument [between them] I think. And the Vietnam War was in full swing; she was spending most of her time involved in that. I’m sure there were other things I didn’t know about, but that was one thing I was aware of; there was a lot of tension about that.” Those times, he recalls, were “painful for everybody.”

His sister concurs. Talking about difficulties between her mother and her from 1963 to 1967, when Nora was moving from school to school, disgusted with the absence of useful alternatives, she recalls that those were also years of grief between her parents. Nora was nearly 18 when Grace finally left Jess, and she says she felt upset and angry even though she understood the split was a good thing, certainly for Grace. Like Grace explaining that life in an extended family is good for children but not for grown-ups, Nora points out that her parents’ divorce was ultimately good for them though it initially made their daughter miserable. Like many adolescents in that situation, she took on a burden of responsibility; she worried about both of her parents and her brother. She remembers resenting Grace’s relationship with Bob; she knows she didn’t want anybody to replace her father. Referring to this now as a “childish and typical reaction,” she explains that she accepted the new family configuration only after several years.

In 1967 Grace moved out; Jess insisted he would not leave the apartment. Karl remembers that “she was floating; she was literally living out of paper bags, staying with friends. Yes, she packed her overnight clothes in a paper bag,” and she stayed days and weeks at a time with Del (Adele) Bowers and with Mary Gandall, both pals from the old playground days, when all their children were small. Clearly Grace thought the apartment on Eleventh Street was hers; she made no effort to find a new home and waited for Jess to leave, which he finally did—though no one seems to recall exactly when.

By then she was able to support herself, working at Sarah Lawrence and making “decent money. Not great, but decent.” She was “all right” financially; “yeah, I didn’t have a high rent, the rents weren’t high there and then.” Asked if, like so many wives, she might have stayed married to Jess too long because she was economically unstable, she says, “No, not then.” This answer suggests that such a situation might have obtained at another time—maybe early in the marriage, early in their lives. Visiting Chicago in 1987, she recognized landmarks near the corner of Halsted Street and Chicago Avenue. “Look at that. That’s where we had that big fight [during World War II, when he was stationed just outside Chicago]. If it had ended differently, my whole life would have been different. Might have been, might have been.”

Exhilarated by her community’s commitment to political action— and its frequent mobilization—Grace was among those who experienced an accelerated rise of consciousness that matched the swift change in the society. The intensity of national and international political movements fused with her own excitement. This is not to say, as we might of so many Americans in that period, that she was radicalized. Grace was already a radical thinker; her analysis of the place and time in which she found herself was always politically rooted. She had been conscious for some years of the mutual impact of citizen and state and had long before developed an analysis of the complicated relationships among capitalism, racism, and imperialism.

Not until after 1970, when she was nearly 50 years old, did Grace Paley’s stories begin to display a feminist consciousness.

The civil rights movement, the peace movement, and the developing coalition to end the Vietnam War were readily absorbed into her world view. Now, however, she began to make some new connections. Her emotional life, her sexuality, and her maternity had not yet been consciously integrated into her world view. Nor had they been spontaneously absorbed once the women’s movement demonstrated that the personal is political. The rising of Grace Paley’s feminist consciousness—its fits and starts, fears and regrets— may be traced in her stories.

Feminism requires more than a clearly demonstrated consciousness of inequity, more than an artist’s accurate—even staggeringly truthful—description of the phenomenon of male supremacy. Feminism demands deliberate opposition to that phenomenon and overt struggle against the power dynamics of patriarchal culture. Readily traced in Grace Paley’s stories is a movement from exceptionally clear descriptions of patriarchy, and characters’ conscious acceptance of, or collusion with it, to outright challenges to the power dynamics of the status quo.

Examining the early years of her political development, scholars might be led to consider Grace Paley feminist in her early portrayals of women and children. The stories are indeed distinctively radical in their placement of women and children at the center. Her characterization of mothers is especially notable: they struggle with the disparity between the patriarchal institution of motherhood and their lived experience. Her other women are also unusual in fiction; witness the tenacious self-control of Dotty Wasserman and the integrity of Rosie Lieber in her first two stories. These are characters whose lives had been left out of canonized literature or had been depicted solely in terms of their connections to men—lovers, fathers, sons, husbands. Women and children are remarkable in Grace Paley’s work for the fact that they appear in stories about their own lives.

Not until after 1970, when she was nearly 50 years old, did Grace Paley’s stories begin to display a feminist consciousness, however. Though the women in her earlier stories often laugh at or seem to ignore patriarchal power, and display attitudes and behavior markedly different from those traditionally presented by both male and female writers, they are nonetheless complicitous in their own oppression, for they do not actively challenge the status quo. In fact, Paley characters and narrators often echo their author’s reluctance to politicize self-definition in their lives. Faith describes (her own) single motherhood in “A Subject of Childhood,” but denies the sociopolitical analysis manifest in her generic situation: “I have raised these kids, with one hand typing behind my back to earn a living. I have raised them all alone without a father to identify themselves with in the bathroom. It has been my perversity to do this alone . . .” (emphasis added).

However grudgingly or wittily—and sometimes quite happily —Grace’s women accepted and played out the roles defined for them by men. Until recently, they still sang a song we recognize as the lowdown blues of women in a man’s world. Singing a song of fathers, sons, and husbands, her women croon and moan, Oh yeah honey, I know he’s no good, but I love him—and variations on that theme. Grace Paley’s version of these blues is written repeatedly into her early stories. In “The Used-Boy Raisers,” for instance, Faith’s narration includes this self-assessment: “I rarely express my opinion on any serious matter but only live out my destiny, which is to be, until my expiration date, laughingly the servant of man.”

Who is “man” to these women? Rosie Lieber (created around 1952-54) knows that her lover Vlashkin—who would have her travel with him “on trains to stay in strange hotels, among Americans” but not be his wife—is “like men are, till time’s end, trying to get away in one piece,” but she still believes that “a woman should have at least one [husband] before the end of the story.” Young Josephine and Joanna (around 1954-56) get mixed—as well as garbled—messages from their mother, a battered daughter, and their grandmother, an abandoned wife. Marvine and Grandma continue to take care of or lust after men, even as they acknowledge that “it’s the men that’ve always troubled me. Men and boys… I suppose I don’t understand them. [My sons are] gone, far away in heart and body.”

In “Faith in the Afternoon” (1958-60), Faith’s wandering husband Ricardo is described as the quintessence of exploitive masculinity, but she misses him, feels sorry for herself in his absence, and weeps for her loss when she thinks about friends who have also lost their husbands—though all are unappealing or present tragic liabilities. Dolly Raftery (mid-1960s) denies and sidesteps her anger, explaining, “Men fall for terrible weirdos in a dumb way more and more as they get older; my old man, fond of me as he constantly was, often did. I never give it the courtesy of my attention.”

There is one exception, and that is the brief flash of hilarious satire in “The Floating Truth” (around 1957-59), in which the “career” possibilities of a young single woman are considered and detailed on a phony resume. Resume entries include a description of her traveling around the country “for five months by bus, station wagon, train, and also by air” to “bring Law and its possibilities to women everywhere”—with the purpose of urging women to increase their consumption of legal services. Another entry on the bogus resume is a stint writing “high-pressure” copy for “The Kitchen Institute Press’s ‘The Kettle Calls’ ” (its title a Yiddish-inflected pun), which was designed “to return women to the kitchen” by means of such fear-and guilt-producing slogans as “The kitchen you are leaving may be your home.” On radio and television, and in ads in “Men’s publications and on Men’s pages in newspapers (sports, finance, etc.), Men were told to ask their wives as they came in the door each night: ‘What’s cooking?’ In this way the prestige of women in kitchens everywhere was enhanced and the need and desire for kitchens accelerated.”

That this character, a young woman seriously seeking work—whose only actual employment in the story is pointless, a waste of her time and mind—should be ironically represented as an agent of the duping and oppression of other women is an unmatched phenomenon in the early and middle years of Grace’s writing. With the young woman’s anger and dissatisfaction articulated in the text— though deftly displaced onto another woman—this story displays a startling recognition of women’s socioeconomic condition; it even includes an incident in which sexual intercourse substitutes for cash payment.

That this story is one most readers and scholars find stylistically disturbing, even incomprehensible, is neither accident nor coincidence. The eruption of feminist politics and the extremely frank, even bitter, view of young women’s life choices are disguised—buried, really—by the extraordinary style and breezy tone of the narrator’s voice. This I-narrator/major character is never named, which makes her difficult for readers to identify with. Her employment counselor is called by at least ten different names, including Lionel, Marlon, Bubbles, and Richard-the-Liver-Hearted, all of which render him comic, masking his exploitive relationship with her. Notwithstanding the fact that he mocks her desire to work for social change “in a high girl-voice” and that his final appearance is an image of him standing in the street to “pee . . . like a man—in a puddle,” his nastiness is less notable than his amusing conversation and especially his sympathetic and fascinating situation: he lives in a car—which, years ahead of its time, has a phone—and he keeps houseplants on its back window ledge. Despite his failure to earn the payment she has made in the backseat, the protagonist is “not mad” at him. Nevertheless, “The Floating Truth” was unique among the collected stories of Grace Paley for many years, stylistically and politically ahead of its time and, in relation to her later development, even ahead of its author.

Not until the early 70s, in three stories ultimately published in Enormous Changes, did Grace Paley’s women openly begin—in words and actions—to question the necessity of the traditional power dynamics and social arrangements between women and men. In the late 60s and early 70s the choices and definitions in Grace Paley’s life were strongly affected by society, just as they were in the late 40s and early 50s, when the socioeconomic position of women in the United States was in flux. In the earlier period women’s position had been deliberately manipulated by such forces as government policy and the spread of rapidly calcifying psychological theory; this time it was shaped by women themselves, organized for social change as women.

“The Immigrant Story” and “Enormous Changes at the Last Minute” were originally published in 1972 in Fiction and The Atlantic, respectively, and “The Long-Distance Runner” appeared in 1974 in Esquire. All were written late in the period preceding the publication of her second book—that is, after 1970—and all contain evidence of a newly rising feminist consciousness. We may contrast them with the original version of “Faith in a Tree,” which was published in 1967 as “Faith: In a Tree” and did not include its final episode yet. As it first appeared in New American Review, the story concludes with Faith’s interest still focused on a potential male lover—whose interest has unfortunately just turned from her to her friend Anna. The addition of the final section about a demonstration against the Vietnam War and its effect on the people in the park, which is the now-familiar conclusion published in 1974 in Enormous Changes, shifts Faith’s consciousness decidedly. Her own enormous change at the last minute lessens—even discards—the effect of her emotional dependence on men.

These three stories provide a clear indication of the future development of their author’s feminism. In “Changes,” Alexandra deliberately chooses to raise her child without a father-in-residence and to do so in concert with her young pregnant unmarried clients (who have previously been less important to her than “the boys”). In “Story,” Faith—as character and narrator—openly refuses to accept masculinity as definitive. When Jack says of his mother and father, “Bullshit! She was trying to make him feel guilty. Where were his balls?” she declares, “I will never respond to that question. Asked in a worried way again and again, it may become responsible for the destruction of the entire world. I gave it two minutes of silence.” In the final story of Enormous Changes, “The Long-Distance Runner,” Faith wishes to create a bond with Mrs. Luddy that will transcend their romantic and sexual attachments to men. When the two women discuss men, Faith expresses the opinion that men don’t have the same creative “outlet” as women, adding, “That’s how come they run around so much,” to which Mrs. Luddy replies, “Till they drunk enough to lay down.” Faith answers, “Yes. … on a large scale you can see it in the world. First they make something, then they murder it. Then they write a book about how interesting it is.” Mrs. Luddy concurs: “You got something there.”

Faith and Mrs. Luddy come to almost the same conclusions as Mrs. Grimble, who is the narrator and central character of “Lavinia: An Old Story.” First published in 1982 in Delta and then included in Later the Same Day in 1985, “Lavinia” was actually written at the end of the sixties. Grace says she “lost it for a long time,” but it is also possible she might not yet have been willing to go public on some of the issues raised in that story. Just as she undermined her sharp burst of feminist consciousness in “The Floating Truth,” she might have simply buried it. In any case, Mrs. Grimble goes even further than the other two women: “What men got to do on earth don’t take more time than sneezing. A man restless all the time owing it to nature to scramble for opportunity. His time took up with nonsense, you know his conversation got to suffer. A man can’t talk. That little minute in his mind most the time. Once a while busy work, machinery, cars, guns.”

It is striking that as she grew more overtly political/feminist in her writing, Grace put such strong statements about men’s place and purpose in this world into the mouths of Black women. There is a difference between the way her white women characters and her Black women characters talk about men. Did she think that Black women have a more negative view of men than white women do? Did she think that Black women are more clear-sighted, and more capable of articulating what they see, than white women? What does it mean that the “mama” Faith finds and learns from when she goes home to her old neighborhood is a Black woman? Had Grace Paley fallen into romanticizing Black women’s strength and their struggle against multiple oppression? Had she fallen into the habit of making Black women the caretakers of us all, Black and white, women and men? Or is she offering respect and admiration here? Is she suggesting that a history of racist oppression, combined with sexism, has given Black women a deeper understanding of the power dynamics of gender than white women have? There are too few Black women characters in the collected stories to answer these questions usefully, but the questions—especially in the light of contemporary Black women’s social and literary criticism—nonetheless must be asked.

These stories presage the further development of their author’s feminist consciousness and the erosion of women’s acceptance of male dominance in her work; they also serve to illustrate the beginnings of that erosion in her own life.

————————————————

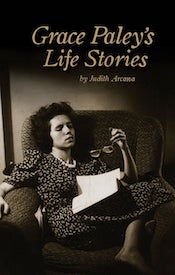

From Grace Paley’s Life Stories by Judith Arcana. Reprinted with the permission of Eberhardt Press. Copyright © 2019 by Judith Arcana.

Judith Arcana

Judith Arcana writes poems, stories, essays, and books. In 2018, two of her books came out in new editions from Eberhardt Press: 4th Period English, poems about immigration, and Grace Paley’s Life Stories, a biography of the globally-celebrated activist and writer. Poems in Judith’s Announcements from the Planetarium (Flowstone Press, 2017) examine memory, wisdom, and aging into new consciousness. She hosts a live poetry show on KBOO Community Radio in Oregon available online. For more, visit juditharcana.com.