In my seventh winter, when my head only reached my Appe’s rib, a White Man came into camp. Bare trees scratched Sky. Cold was endless. He moved through trees like strikes of Sunlight. My Bia said He came with bad intentions like a Water Baby’s cry.

Old Ones said this Man was the craziest White Man they had seen. Young Ones said this was the only White Man they had seen. Our wise One, Flatbird, asked Agai River if this was the very White Man sent from our Old Stories, but River did not answer.

See. He does not come with Horses, People said. He does not have pelts to trade.

In that black winter, His clothes were tattered, brittle-cold; they fell from Him in pieces like leaves fall from Trees. Snow had scraped His feet to bones.

At first, People were afraid of Him. How did He survive? People asked. Only a crazy One could survive with no covering and no food.

He is no Man, some said. Look at His skin.

His skin was frail pond ice when Moon lifts day. He shook like a dog shakes water. Crazy shaking. Day and night He shook. My Appe fed Him and covered Him with our best robes.

For many days, White Man sat beside our cook fire rubbing His palms together. He was like a hunk of frozen Buffalo; He stole the fire heat. And after many days, He became like the white Trees that line the Turtle marsh. His bark peeled. We saw bone shine, His back bared to wings. His fingers thawed, slushed, then stank. His penis turned to ash.

Our People came to look before He died. Touched His head. Prayed.

Flatbird said, I have no Medicine for this crazy Man. His eyes are washed of color.

See. He is already turning to Sky.

I sat with the dying Man. I watched over Him, as my Appe asked.

White Man lived to see tall grass return, lived to welcome Agai—Agai so thick in River we heard them speak. White Man lived to see us dance and watched us with His lowered head like an Elk with swivel eyes.

White Man lived to fool us.

He lived.

Follow Him, my Appe told me. Learn His tongue. Find out what He knows.

My Bia did not like White Man. She chewed Deer hides soft, made many baskets, all the while her scout eye perched on me, on Him, on His hands’ pale flutter around everything I touched, and did.

This Man spoke a strange tongue. All day long He spoke. On and on He spoke. His words made no sense.

What do you think He is saying? my Appe asked. He is all the time talking.

Fa Ra Siss Huck Ja Ja Ta To Eat Pa Ra, I said.

Appe took me to River to fish. Alone. He hid me from Bia.

I will teach you to fish, Appe said, so that you will know. Far off you will know to fish to stay alive. You must know how to speak to Water, but it is All to know how to listen. Listen like River listens to Agai.

When we netted enough to feast, Appe prayed. For a long time, he prayed. And then Appe struck River bushes with two sticks. He tossed head-sized rocks into tall grasses and grass Birds beat their wings like drums and flapped around us and away.

Appe cupped his ears. He looked to see if White Man followed me, if Bia was near. From all signs we were alone. He took off his moccasins and signaled me to follow. He took hold of my hand and together we stepped into the strong current of Debai-lit Water. We hid deep in shadowy scratch where bramble roots become one with River. Water was cold. Agai trembled close to our feet and held to us. I crouched beside Appe in hiss-speak of Water. I listened. I watched.

Appe looked down into Water and hooped his arms. Currents cracked over smooth stones and shivered around us. He waited until a round seam of Water appeared. Waves rushed past his circled arms. He waited until his breath no longer puffed.

Appe pulled me into the center of River, a still circle. I hold you here, my Baide. I ask River keep you as safe as I do now. As long as you are near River Water, I send my spine, my string gut, my blood to protect you.

I had a trouble dream, my Baide, Appe told me. In my dream, my own Baide spoke many tongues. Water chose her to be Long Spirit who remains after all are no more. A strong Baide who must speak with Monsters.

I was Appe’s only Baide. He was speaking about me, but did not wish his dream to fall over me.

I peered down into the clear River spot, but saw only Agai, their long snouts, their red fins flutter, their round round eyes.

Our Old Ways protect you, he said. Give me your hand. Can you feel it, Baide? River shakes tiny shakes now. No-longer-living is here. Feel it in your gut, my Baide. Earth changing, moving away from us. Little by little it goes.

Do not let Monsters know you understand. Hold to yourself and you will be safe, Appe said.

I opened my hands and held them over River and felt shaking in me. Outside me.

Sickness is near, Appe said.

We heard People of Sagebrush were struck by sudden Sickness. Black circles boiled up from deep in their bodies, burst, and robed them in antler velvet. The People died like rotten plums, split open, their skin fizzing stink. Their faces turned the color of Mountains before dark. Whole Villages rotted. Their angry Spirits plague Rivers now. Villages of Spirits searching for what was taken.

Appe knew what others did not know. Not Flatbird. Not Bia. Not Camehawait.

Can you hear Them? Appe asked. Trees scream with wind at night. Fury spits from Debai-lit skies and breaks branches in darkened woods. Their anger rattles rocks along River edge. Seething. Chittering. Close and All Around. So many lost. The Sickness they carry jickles like dry seedpods. Like Bad Medicine crouches in bone. Soon we will all be touched by Sickness we cannot heal.

Listen to me Baide. One day you will be far from me. But what we have taught will not leave you. Learn all you can and you will go on. From here now, and for many generations, far far into where I cannot see—you will be. I cannot tell you how, he said.

My Appe’s words trembled in me. All day my knees shook.

White Man looked at clouds. Slept like a baby in a bundle cradle.

Bia and I gathered Tree nuts, brown grass seeds. You look like trouble coming, Bia said to me. You are too young to be broken-mouthed. Your face is tatter-poled as an old Woman teepee carrier.

It is the wind, all night, I said.

Puh, Bia said. It is you drag White Man around like pull dog. I see. I see it is no good for you.

Listen. Learn from Him, Appe told me when we were alone.

How come Bia does not wish me to learn from White Man? I asked.

I think you ask why she does not believe me. Appe laughed. No People live long without One-Who-Challenges. We fall asleep in our tasks. Your Bia is like the dog that yaps at Weta. Weta growls and sniffs and digs with big claws. But Bia keeps her push. She is not afraid of sharp teeth or Weta snarls. Maybe she is right. You decide.

Bia saw what Appe did not see and Appe saw what Bia did not see.

You must hear the White Man’s voice, Baide, Bia said. You must hear Him differently than our Men hear. We Women hold our People’s language, and our language. Your own language is here, she said. She patted my chest.

Bia held my face and whispered, Men do not know Woman carries a voice inside her to help her live. When you stop hearing your voice you are nothing more than snare bait. You are bone crackles in Weta’s teeth.

Bia and Appe followed me. Buzzed around me.

Listen, Appe said. Listen to the steady tap of bees as they butt their tails against flowers.

Listen, Bia said, to the heavy smack of Wetas’ tongues against their teeth.

Listen, Appe said, to wind as it catches in Land dips.

Listen, Bia said, to the slather-drool in a hungry Wolf’s mouth. And in a Man’s mouth, she said. Puh.

Bia listened with the backs of her hands and the back of head. She listened with her rumble gut.

All things have their own way of being in this World, Bia said, a pattern, a footprint, sounds to make babies laugh, sounds to make children see trouble. Hear this, my Baide, in the gristle chew around campfires, in the laughter and mean jokes All Around, listen close. Stay awake. All speak carries warning—the tight-foot tread of Coyote around camp Water, the yowl of Fox throwing his voice, the scary titter of Agai when Water bowls in shallows. Listen to the White Man to survive. Let his voice set up in your head like coagulated blood along the ridges of scalps.

I listened as I made moccasins for White Man. I listened as I made Him Deer shirt and leggings. He wobbled like a fawn behind me. He talked and talked. He talked every bush, every blossom, every seed. I came to understand my own voice through His voice. Every tongue tap. Every voice Song. And then, slowly, White Man’s sounds became words and His words held meaning.

This I learned from Him: He came from Civilization.

His people came from across

big Water.

His Medicine Spirit was Jesus + He had seen the Devil.

His people have many many words for the World.

He tried to teach me all of them.

When White Man could not walk far He used me as His walking stick. He gripped my shoulders and stumbled behind me. Bia slapped His hands if He fell me. She stayed as close to Him as a suck bug. He watched me as I picked berries, plucked grasses, kept cook fires, dried Agai, played games.

You work as hard as a Man, He told me. But you are a little girl.

I did not understand and He pointed to young Men and cradled His cheek in His hand and closed His eyes. He put His arms around a large rock, grunted, and pointed at me. He smiled.

I looked away. He smiled too much. He smiled at everything like He knew something we did not know. He could not know our ways. The way Men work. The way Women work. Women hands are stained with blood, childbirth, and Men’s blood. Ripe berries. Butcher blood. He could not know I work harder than Men because I am learning All Ways to survive.

Women carry childbirth and Death, blister snow and suckling babies, Weta growls and Weta attacks in berry bushes, Enemy sneak-ups, War parties return, and War parties not return. Women survive carry-work every day. All year. Year upon year. Across Prairies. Across Rivers. Across Mountains. In All Ways, Women carry Men in all their ways. Women carry Men to survive.

White Man was as lazy as a lazy Bird plucking lice from a Horse butt.

Appe told me to keep listening.

White Man drew scratches in soft River edges. This line means the beginning of a word. This is the word for SUN. He lifted His hand to Debai and drew a circle with spikes and pointed to His scratching, then pointed up to Debai. The round white circle in the Sky, SUN, He said.

When Weta snuffled in the willows, He pointed. Bear, He said. Dangerous Bear. He made his hands curl like Weta claws and clawed Sky. He named all the Fish. He named Everything.

There are four Seasons, He said. Winter brings cold and snow. The opposite of Winter is Summer. Summer brings heat, days of plenty. Spring brings renewal, new leaves, new hope, new Life. Autumn brings frost and shimmers with golden leaves. He lifted his palm toward River and pulled his fingers together as if He sprinkled fat over soup. Shimmer, He said. Glitter. His eyes watered. Light over Water is beautiful. Autumn is beautiful, He said.

You are beautiful, He said.

When I asked what beautiful means, He swept his open hand across the Landsight from Earth to Sky to Earth.

Beautiful, He said. He touched small red-speckled leaves. Beautiful, He said again, lifting tiny rosebuds to my face. Beautiful.

Puh, Beautiful means He has come to destroy us, Bia said. He is foolish. Pay no attention to His petting words. Only what He does. Petting words will fool you. What He does is what matters. Remember our long-ago stories. He is only one of many Enemies to come.

I listened to Bia and tried to understand the many ways she told me to listen and not listen. I became as watchful as Coyote blinking in the underbrush.

White Man ways of living are strange to our ways. If all White Men live in blind Seasons, they are like a Man with one foot snared. They are asleep to the changing Moons. I was born in the Season of Budding Moon. Bia said I was born to understand plants and to use them to their best. I was born to gather, to see the World around me, to listen, to tend. Appe was born in the Season of Coyote Moon. He was born to track, to watch, to pay attention. He sees things we cannot. Bia was born in the Season of Rutting Moon. No one has to be told this. It is clear she is always toothed with anger, bubbling steam, loud. No body, no animal, no change gets in her way. I did not ask White Man what Season He was born in or what His name was. He told me He wished to live free from the Life He once lived. Free from the People He once knew.

When White Man spotted Pop Pank swimming, He dove under River ice to grab her and she dipped her head, and disappeared. He dove down, again and again. He dove into River where only Water Spirits go. He tried until His belly turned blue and His white skin shook like a blanket of mice. He rose empty-handed every try.

He held my shoulders, and Bia looked up from her cook fire. Crows flapped, clawed smoke, grasped and flittered and squawked away.

I heard of your People’s Medicine, White Man said. But I have never witnessed it before now. His eyes were bluster blue. His eyes were ruptured eyes spilling blue beads. He clapped. His spittle silver beads. If I could have plucked His eyes, I would have made a necklace. His eyes were beautiful. I would have sewn His eyes on to my robe.

Pop Pank is not like ordinary People, He said. Do you understand? White Man was Crow at first feeding. Crow laughing at a broken gut spilling maggots. ă’-rah

Ordinary, He said again. Like you and me. He pointed to me and then to Himself.

He squatted low and then pointed to Pop Pank wrapped in a blanket beside her Gagu, Mud Squatter.

Pop Pank has what my People call magic, He said. He made a fist and opened His fingers to Sky. She can do the impossible. She can breathe underwater. White Man made the sign for Fish and then pointed again to Pop Pank. He shook His head and smiled like an old Man who returns from battle with more scalps than wounds. He looked at Pop Pank like a baby looks at what-cannot-be-seen.

What did He see? Pop Pank was a runt among runts. She had lived through five turns of Seasons. Her knees were knobbly as Moose legs. Her hair did not grow. She could run as fast as any Woman, and faster than any Man, but she had a thin, broken look. She did not work like Women worked. She learned her ways from her Gagu. All day they swam together through Seasons. I looked and looked until I saw what He saw.

Pop Pank was sinew and bone, small as a Trout. Her eyes were the color of marsh Water—murky, muddy, and come together like a teardrop at the center. Fish eyes.

She is different, White Man said. She is special among all others.

I learned Pop Pank would be special among White People. I learned White Man was no longer related to animals.

When seed grasses rattled and second summer came blue-Mooned and hazy, White Man wrapped Himself in grass blankets I taught Him to weave. He took Appe’s Horse and rode into the Trees where He had come from. He rode away at first rising when mice skitter beneath dry grass shells and Buffalo flowers lift their heads.

Puh, Bia said to gathered Women. He was no good. I told you. I told all of you. We should have killed Him when He was pitiful. Now He steals our Horse and laughs. He was not crazy. Puh. He was all along Enemy. He was all along worthless thief.

White Man promised He would come back. I waited for Him. I stood beside River and listened. I stepped into knee-deep Water where slippery roots catch ankles to hear the Faraway. I dreamt of Agai crying, breaking their long bodies on rocks as they leapt up and over Water falls and Ogres, to return Long Spirit to us. I watched the edge-of-dark-woods where He had first shown His self and Bia grabbed me and told me to be awake to what was.

White Man will return, Bia said. There will be no good Medicine in His comeback. He will curse us with His many Brothers. He will return like lice.

I did not see White Man again.

Flatbird said, this White Man was bad Spirit come to tell what is to come. All Around us, Flatbird said, All Around.

Puh, Bia whispered. What do I not know?

__________________________________

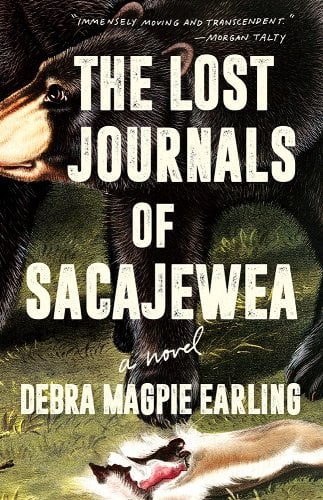

From The Lost Journals of Sacajewea by Debra Magpie Earling (Minneapolis: Milkweed Editions, 2023). Copyright © 2023 by Debra Magpie Earling. Reprinted with permission from Milkweed Editions. milkweed.org