The Literature of Ezili, Vodou Spirit Force of Queer Black Womanhood

Why Do Artists Return Again and Again to Ezili?

Water is eternal summer, and the depths of winter, too. When I arrived on the west bank of the Mississippi River in August 2005, everything, everything in my life was midsummer, bright, and new. I had just moved to Minneapolis to start a new job at a new university, was living in a newly painted apartment by a glinting lake I ran around every new morning, was newly single, and every day wore new white clothes and answered to a new, seven-day-old name, Iyawo, the name of a priest newly initiated in the Ifa tradition. So who would be surprised that even though I hadn’t finished my first book—literary criticism caressing the writing of Caribbean women who love women—I was suddenly inspired to research a new, second project. An analysis of 21st-century Caribbean fiction by queer writers, the project seemed bright and shiny as beaches and I rushed into it headlong, in one weekend penning an article that I thought would become the introduction to my next book.

But the longer I sat with this book the more choked, the more stagnant it became. The directions I followed and answers I found seemed too easy, too pat—and while this apparently pleased funders and tenure committees, it left me cold and uneasy. So I went back to texts I’d gathered for my project and other texts I’d loved in the past ten years, looking for what unexpected things they might have to say about Caribbean lesbian, gay, transgender, and queer experience that I was still missing. I quickly found my answer: nothing. This was because the vocabulary I had been using to describe these authors, the descriptors that they used for their own identities—queer, lesbian, transgender—appeared nowhere in their work. Nowhere. No characters, no narrators, no one in the novels used these words. Instead they talked about many kinds of desires, caresses, loves, bodies, and more. And over and over again, they talked about something that was such a big part of my life, but that I never expected to find in most queer fiction: spirituality, Afro-Caribbean religions.

Not one of these authors wrote about “queers,” but almost everyone wrote about lwa—that is, about the spirit forces of the Haitian religion Vodou. And, finally, finally tuning into this other vocabulary, I was fascinated by the recurrence of one figure, who multiplied herself in these texts as if in a hall of mirrors: the beautiful femme queen, bull dyke, weeping willow, dagger mistress Ezili. Ezili is the name given to a pantheon of lwa who represent divine forces of love, sexuality, prosperity, pleasure, maternity, creativity, and fertility. She’s also the force who protects madivin and masisi, that is, transmasculine and transfeminine Haitians. And Ezili, I was coming to see—Ezili, not queer politics, not gender theory—was the prism through which so many contemporary Caribbean authors were projecting their vision of creative genders and sexualities. Finally, five summers later and into the middle of a winter, I was coming to see.

That winter, discarding plans so carefully laid out in grant applications, I decided I wanted to write a book that would be a reflection on same-sex desire, Caribbeanness, femininity, money, housing, friendship, and more; I wanted to write a book about Ezili. My loving, unfinished meditation on Ezili would open space to consider how, as Karen McCarthy Brown writes of the pantheon, “these female spirits are both mirrors and maps” for transfeminine, transmasculine, and same-sex-loving African diaspora subjects. And it would reflect on Ezili as spirit, yes, but also on Ezili as archive. That is, I wanted to evoke the corpus of stories, memories, and songs about Ezili as an expansive gathering of the history of gender and sexually nonconforming people of African descent—an archive which, following Brent Hayes Edwards, we might understand not as a physical structure housing records but as “a discursive system that governs the possibilities, forms, appearance and regularity of particular statements, objects, and practices.”

“Ezili, I was coming to see, was the prism through which so many contemporary Caribbean authors were projecting their vision of creative genders and sexualities.”

I wouldn’t be looking to cast light on the (somewhat familiar) argument that this archive shows how spirituality allows trans* and queer people particular kinds of self-expression, sympathetic as I may be to such claims. My choice to follow the lwa instead would explore how a variety of engagements with Ezili—songs, stories, spirit possessions, dream interpretations, prayer flags, paintings, speculative fiction, films, dance, poetry, novels—perform black feminist intellectual work: the work of theorizing black Atlantic genders and sexualities. This is the kind of theorizing Barbara Christian asked us to take seriously when she reminded feminist scholars “people of color have always theorized . . . and I am inclined to say that our theorizing (and I intentionally use the verb rather than the noun) is often in narrative forms, in the stories we create, in riddles and in proverbs, in the play with language, since dynamic rather than fixed ideas seem more to our liking.”

Reflecting on Ezili’s theorizing, then, I look to situate a discussion of black Atlantic genders and sexualities not primarily through queer studies, but rather within a lineage of black feminisms: a lineage which pushes me to ask what it would sound like if scholars were to speak of Ezili the way we often speak, say, of Judith Butler—if we gave the centuries-old corpus of texts engaging this lwa a similar explanatory power in understanding gender.

*

Why do artists return over and over again to Ezili—not Danbala, not Gede, but always Ezili? I knew easy answers to this question.

One of Vodou’s complexities is that though day-to-day practice of this religion is dominated by women and masisi, few of its lwa are feminine spirits. The pantheon of spirits known as Ezili is the richly, expansively, riverinely powerful exception to this rule: Gran Ezili, Ezili Freda, Ezili Danto, Ezili Je Wouj, Ezili Taureau, Lasirenn, and others are immensely influential for all those practitioners who embody and/or desire femininity. Ezili’s most prominent paths include Ezili Freda, the luxurious mulatta who loves perfume, music, flowers, sweets, and laughter but always leaves in tears; the fierce protectress Danto; and Lasirenn, a mermaid who swims lakes and rivers where she invites women passersby to join her and initiates them into mystical (erotic?) knowledge. Indeed, no other lwa maps and mirrors queer femininity and womanness in the way Ezili does.

Because of this prominent, unique femininity, Ezili is also, as Colin Dayan notes, the lwa who most often appears in Caribbean literature, and her faces prominently mark work by Haitian women novelists from Marie Chauvet to Edwidge Danticat. In anthropology as well, Elizabeth McAlister claims, “most fieldwork and writing on gender and sexuality in Vodou focuses on the spirit or goddess Èzili.” Building on these literary and anthropological writings, key theoretical texts in Caribbean gender studies often take Ezili as their focal point. The most foundational of these is Dayan’s “Erzulie: A Women’s History of Haiti.” Her fiercely insightful, unrelentingly iconoclastic essay argues that the pantheon of Ezili, with their intimate, obscured connections to enslavement and emancipation, offer a more complex way of knowing Haitian womanhood than hegemonic feminism can produce—one that preserves “histories ignored, denigrated, or exoticized” by standard historiography, and “tells a story of women’s lives that has not been told.”

“It remains a black feminist necessity to explicate, develop, and dwell in the demonic grounds of realities other than the secular Western empiricisms that deny black women’s importance in knowing, making, and transforming the world.”

This is a story that complicates feminine sexuality, for “though a woman, Erzulie vacillates between her attraction for the two sexes.” And, though artistically, gloriously feminine, Ezili also quite spectacularly explodes gender binaries: “She is not androgynous, for she deliberately encases herself in the trappings of what has been constituted in a social world (especially that of Frenchified elites) as femininity. . . . She takes on the garb of femininity—and even speaks excellent French—in order to confound and discard the culturally defined roles of men and women.” Dayan opens academic space—or better, academic demonic ground—to think of Ezili as both sexually and gender queer, but never develops this possibility. She instead goes on to analyze novels in which the lwa appear in resolutely heterocentric plots. The novels, films, and performances I turned to enter intertextual conversations with many of these earlier texts—novels, ethnographies, theories—but, rather than keeping the Ezilian sexual creativity they find in the margins, open directly there, moving deeper into where other possibilities for gender and sexuality break open in Ezili’s arms. And I, in turn, try to follow.

But there was also a less straightforward, more sinuous answer that inspired me as I began this project. In her watershed study Divine Horsemen: The Living Gods of Haiti, Maya Deren writes of Ezili as “that which distinguishes humans from all other forms: their capacity to conceive beyond reality, to desire beyond adequacy, to create beyond need. . . . In her character is reflected all the élan, all the excessive pitch with which the dreams of men soar, when, momentarily, they can shake loose the flatweight, the dreary, reiterative demands of necessity.” In other words, Ezili is the lwa who exemplifies imagination. And the work of imagination is, as other scholars have already beautifully stated, a central practice of black feminism—indeed, it remains a black feminist necessity to explicate, develop, and dwell in the demonic grounds of realities other than the secular Western empiricisms that deny black women’s importance in knowing, making, and transforming the world. As Saidiya Hartman writes, the deepest, most pathbreaking black feminist scholarship around sex and sexuality may be to imagine new possibilities for black women’s bodies, stories, desires: “to imagine what cannot be verified . . . to reckon with the precarious lives which are visible only in the moment of their disappearance.” Reaching even more broadly, Grace Hong asserts, “Calling for a black feminist criticism is to do nothing less than to imagine another system of value, one in which black women have value.”

As a principle of both femininity and imagination, Ezili calls out a submerged epistemology that has always imagined that black masisi and madivin as well as black ciswomen create our own value through concrete, unruly linkages forged around pleasure, adornment, competition, kinship, denial, illness, shared loss, travel, work, patronage, and material support. So in addition to engaging Ezili to enter conversations with well-known literary and academic texts, I see queer artists turning to her as the figure of a submerged, black feminist epistemology: one that, like their own work, testifies to the important antiracist, antiheteropatriarchal work that imagination can do, when it creates mirrors in which the impossible becomes possible.

__________________________________

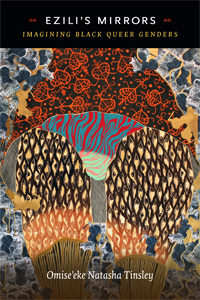

From Ezili’s Mirrors: Imagining Black Queer Womanhood. Used with permission of Duke University Press. Copyright © 2018 by Omise’eke Natasha Tinsley.

Omise’eke Natasha Tinsley

Omise’eke Natasha Tinsley is Associate Professor of African and African Diaspora Studies at the University of Texas and author of Thiefing Sugar: Eroticism between Women in Caribbean Literature, also published by Duke University Press.