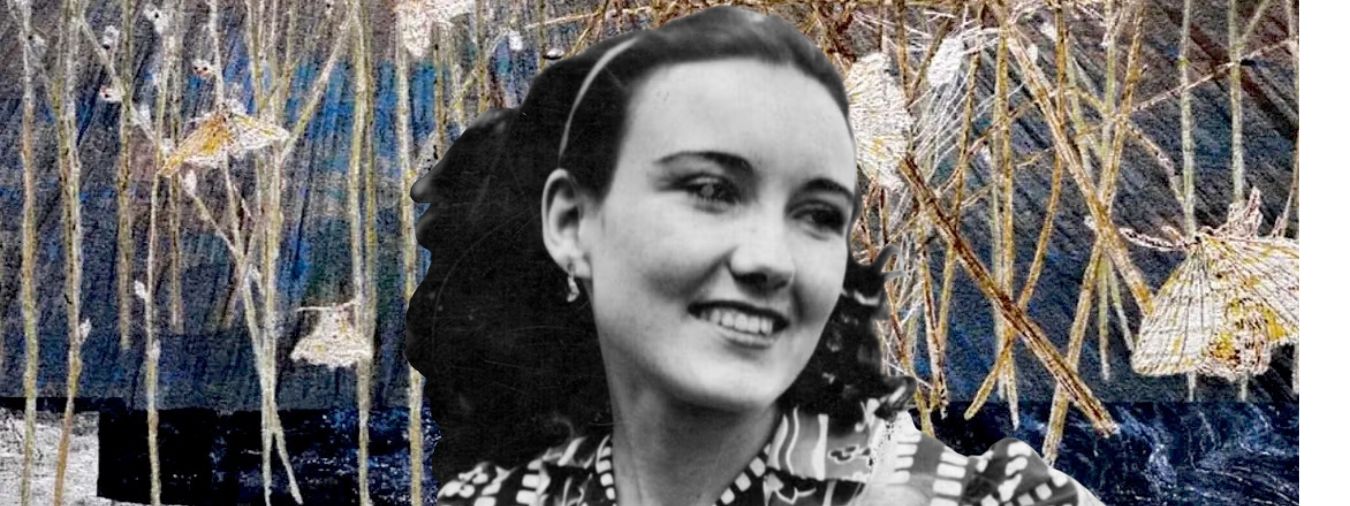

The work of Barbara Comyns always felt like a secret, as if she were writing, speaking only to me. A literary outsider, Comyns had almost no formal training in writing, and didn’t publish her first novel until 1947 at the age of forty. She published ten novels and one short memoir, but it’s her penultimate novel The Juniper Tree that strikes me as the most developed embodiment of her aesthetic project.

Part fairy tale, part domestic tragedy, The Juniper Tree inherits the fairy tale tradition as a psychic compulsion that structures the events, symbols, and aesthetic sensibility of the novel. But what makes The Juniper Tree distinctive is the gentle, oblique texture of its psychological and material realism, and the way Comyns wields this unique comingling of realism and fabulism to create an astonishing suspension of disbelief and narrative structure. There’s a magic here that makes me think I too have lived it.

But where does such a beautiful book come from? How, at the tender age of 75, does one suddenly write a masterpiece? Well, the short answer is that one does not. One builds up to it. Comyns wrote her way towards The Juniper Tree over the course of her entire career. Introductions to her novels often praise her as an outsider artist, a person unencumbered by the stiffness of a formal education. But given the sly intelligence that lurks beneath Comyns’ glossy prose, that label doesn’t feel quite right.

Maybe it’s just ornery romanticism, but I’d like to think that all art is in some crucial way outsider art. Or all the best art is outsider art—learnt alone, through the pangs of trial and error. And that’s how I read Comyns earlier work. Lovely, bewitching trial and error. She flops and flails at times, but in each of her earlier novels she’s writing her way toward her better work, specifically The Juniper Tree.

This notion presupposes that The Juniper Tree is Comyns’ best novel, which may or may not be true. Many readers prefer The Vet’s Daughter, and I would venture that many more would prefer Mr. Fox and The Skin Chairs if they were more widely available. The relative greatness of each of these books is largely a matter of taste and appetite—some readers like their heroines young and tragic, others older and more hopeful. Some prefer a heavier touch of the gothic (The Vet’s Daughter), others a more bucolic optimism (The Skin Chairs), and still others a good wartime fairy-tale mashup (Mr. Fox). De gustibus non est disputandum—a phrase that a Comyns’ heroine might call “the kind of stuff that appears in real people’s books” (Their Spoons Came from Woolworths, 41).

But some things, such as structural complexity, tonal calibration, narrative distance, motif development, and the intermingling of subplots, are disputable, and in the case of The Juniper Tree, Comyns exerts a more sophisticated mastery of these elements of craft. Over the course of her novels, Comyns works her way through autobiography to a more nuanced apprehension of her own unique genre, a sort of fairy-tale infused autofiction, a fussy label that’s just to say she used literature to distill certain truths and experiences of her own life.

It’s hard to say exactly what genre Comyns is writing in. She variously employs the conventions of a gothic novel, a (bewildering) family portrait, a bathetic melodrama, and a fairy tale gone wrong, but what seems to be most dynamic and formally significant in her novels is her use of voice.

Apart from her three works written in the third person (Who Was Changed and Who Was Dead, Birds in Tiny Cages, and House of Dolls), Comyns writes in an intimate first-person. Her narrow to non-existent psychic distance gives each of her first-person novels a close, confidential feeling. Comyns’ narrators are chatty and relaxed. They do not press their intelligence on the reader—in fact, they seem to obscure their understanding and knowledge, often for their own safety or survival. They are all women and girls displaced and dispossessed from any meaningful agency or control over their own lives, and their syntactical sleight of hand seems to derive from this subordinate social position. It also makes for some highly entertaining prose.

Reading Comyns is like reading a women’s magazine, only to realize ten pages in that she’s up to much, much more. Over the course of her ten novels, Comyns indicts the pre- and post-natal care of impoverished women, she makes a convincing case for a national welfare and health system, she explores the psychological impact of domestic abuse and economic dependency, and she does all this using the voices of subaltern women and girls.

Of course, Comyns’ narrators wouldn’t put it that way. They would say they’re telling their story, just as the narrator Sophia does in the first line of Their Spoons Came from Woolworths: “I told Helen my story and she went home and cried.” Like Sophia, all of Comyns’ narrators write with such a fluid and effortless command of their prose that we feel close to their experiences not as art, but as life lived. The transformation from autobiography into fiction becomes particularly clear over the course of her first four novels—Sisters by a River, Who Was Changed and Who Was Dead, Our Spoons Came from Woolworths, and The Vet’s Daughter. As Comyns keeps writing, she seems to be learning exactly how to calibrate her psychic distance to mold her life, or adjacent imagined lives, into art.

I think that writing was one of the ways that Comyns made or unmade sense in her own life. That she used writing, like art, to understand her life, combining and recombining her own experiences until they congealed into something apart from her, something like art. She did have an awful lot of life experience, much of it difficult. She could have, like the narrator Vicky’s more conservative and sensible sister in A Touch of Mistletoe, pursued a wealthy husband, or a simple life with a simple job in a simple town. Thank God she didn’t.

Instead, she slogged it out in her life and her novels, beginning with Sisters by a River. First serialized in Lilliput Magazine as The Novel Nobody Will Publish, it’s easy to see why the book got that title. It’s a trying read, stocked with so much life and symbolism and imagery that it’s difficult, or at least unrewarding, to extract much meaning from it.

The story itself is simple: five sisters grow up in an English country household that’s characterized by violence and neglect. The once grand estate where they live is largely in ruins, their father is mean and dangerous, their mother deaf and removed, and their grandmother capricious and terrifying. The sisters raise each other in a world filled with flooded lawns, drowned pigs, levitating girls, visitations from God, bats, rats, stilts, edible eels, and more.

What is Comyns up to in this bizarre and off-putting first novel? I think, quite simply, she’s learning on the job. She’s figuring out not just her interests, but her way of communicating them. She’s over-emphasizing the first-person childlike naiveté that she’ll later perfect, she’s overwriting the long, elegant sentences she’ll later trim, and she’s mechanically inserting the magical and social realism that she’ll later more thoughtfully construct as organic parts of her story. In Sisters by a River, Comyns is writing without artifice, with only her own children as audience. It might not be all that great, but it’s necessary.

The displacement of trauma into magical events, the fixed interest in, and cruelty toward, animals, the abuse of fathers, the fixation on furniture and paint and color and clothing—all of these things will return throughout Comyns’ novels. She’s exploring her interests, and not really leaving anything out. As much as Comyns can remember from her childhood seems to be chronicled here. She is, in a word, overwriting. What a great way to begin a career—say everything you can think of, so that later you can prune the excess.

Reading the opening paragraphs of Sisters by a River is like looking at an infant version of The Vet’s Daughter or The Skin Chairs or The Juniper Tree. We have the same attention to color and imagery. The same fairy-tale sense of dispossession. The same defamiliarization of a lunatic world. The same ivy and fir and walnut trees and babies. But Comyns hasn’t quite landed on how to manage it all. The daffiness, while enchanting, is just too damn daffy. Her child narrator, though authentic, writes too much like a child. Comyns has undershot her psychic distance, keeping her voice too close to her own experience and childhood psyche to let the reader in.

If Sisters By a River skews too closely to autobiography, then Who Was Changed and Who Was Dead, her third novel, overshoots the mark. Here, Comyns writes in the third person. She’s attempting to get her distance right. It’s as if she knows, or intuits, that the psychic distance in Sisters was too cramped, and now wants to remedy it. So, she goes whole-hog third person with an exhaustingly equitable narrator and a plot based on a French newspaper article rather than personal anecdotes.

In Who Was Changed and Who Was Dead, the narrator roams from character to character in a country village, switching focus so suddenly and frequently that the reader doesn’t quite know whose story it is. Presumably, it is the village’s, but in giving up her skillful first-person narration, Comyns has diluted the lifeblood of her storytelling.

Our Spoons Came from Woolworths presents the second half of the cannon of Comyns’ heroines—a young mother in distress. The themes that haunt The Juniper Tree—women’s financial insecurity and dependence on men, the complications of their problematic relationship to children and domesticity, a sense of wonderment and horror about nature and human relationships—begin to surface in Our Spoons Came from Woolworths. And, just as in The Juniper Tree, these preoccupations are all infused with a childlike and devastating tone.

Unlike Bella, Sophia, the narrator of Our Spoons Came from Woolworths, cannot yet grab the reigns of her fate. At the end of the novel, Sophia ends up married to another man, a kinder man, basking in the glow of a lovely afternoon, telling her story—the novel itself—to a friend over coffee. She has survived poverty and single motherhood, but she hasn’t made much of her life other than as a subject of her husband’s painting. That might be a stingy interpretation—maybe surviving the trauma of poverty as a young single mother is triumph enough. Still, Sophia seems less entire, less in command, and less dynamic than Bella, Comyns’ late-style creation.

Perhaps the ease of this novel’s end is related to its easy structure. There isn’t much (other than her signature mastery of voice) holding the book together. No network of symbol or allegory. No binding of event to image. There are repeated feelings and fixations, but we don’t yet have the kind of integrated narrative architecture that holds The Juniper Tree together. We have a tale simply told, no matter how arresting it is.

Comyns’ first three novels read like the outpouring of different journals. Unformed, free-flowing, and lightly organized. There is little story structure that might build tension or suspense. Little long-term plotting of symbol and image. Instead, Comyns gives us streams of zany happenings that seem all the zanier for their lack of place and purpose in a larger narrative. What unifies each of these novels is their voice—a feature that’s strong enough to carry them through to publication.

At the risk of diminishing the integrity of each of these books, it helps to place them in concert with each other, and to see them as precursors to her later, more assured work. If we were to chart Comyns’ evolution, it would look, somewhat rudimentarily, like this: childhood autobiography (Sisters by a River), adulthood autobiography (Our Spoons Came from Woolworths), a shift to a hugely removed third-person tragicomedy (Who Was Changed and Who Was Dead), and finally a more cohesive calibration of autobiography and tragedy: The Vet’s Daughter. It’s as if Comyns must purge the demons (both silly and serious) of autobiography and then reject them in order to get her narrative distance and voice right later on. By the time she gets to The Vet’s Daughter, Comyns has a more elegant and effortless command of sentence and scene. She knows how to inflect her child narrator with an adult sensibility and cohesiveness. She knows, now, how not to make the whole thing too damn daffy.

Comyns’ fourth novel, The Vet’s Daughter, tells the story of Alice Rowlands, a young girl with an abusive father. After many tragic things happen to Alice—her mother dies, she is entrapped and escapes a rapist, she is tormented by her stepmother—she discovers she can levitate. When her father, a cruel veterinarian, attempts to display her levitation publicly for profit, Alice ends up trampled to death. It’s a sinister tale with a complex first-person narrator, the first of Comyns’ to successfully mix elements of autobiography with magic. It’s strange and fantastic. Comyns writes of the everyday world with the same enchantment that we’ll later see in The Juniper Tree, the same uncanny way with detail and observation.

But what is different from The Juniper Tree is the level of control—in style, in structure, and, relatedly, in content. Alice can exert no control over her own life. She cannot escape her father. She cannot develop a self. Magic is the only self-expression available to Alice, the only reasonable outcome for a character so dispossessed by abuse.

Out of all the distressed and hopeless young girls and women in Comyns’ dappled storyverse, Alice is the most hopeless, the most distressed. She cannot see a way to freeing herself from her father. She can only let events happen to her. And, as such, the only manifestation of her will is the psychic displacement that magic affords. Alice ends up in the realm of the occult because it’s all that’s left to her. She can neither escape nor develop precisely because of the abuse and neglect she has suffered.

Like Alice, Comyns doesn’t go to great lengths to control or structure her story. It’s a straight shot from beginning to end, a “fever dream” as Kathryn Davis aptly observes in her introduction. There is some repetition in the more macabre elements such as the monkey skull on the mantle, and a handful of moments of foreshadowing when Alice dreams of floating and then explores her startling ability to levitate, but The Vet’s Daughter does not develop a more elaborate narrative structure. It has the singularity of focus and absorption of a nightmare, not the breadth of novel.

Still, The Vet’s Daughter is a fantastic book, a ghastly and gorgeous bauble. The monkey skull, the dog-skin rug, the man with the ginger mustache bookending the whole chilling affair—The Vet’s Daughter is, in so many ways, a rehearsal for The Juniper Tree. Comyns has trimmed the excess of images in Sisters by a River and, in doing so, achieved an aesthetic unity that makes The Vet’s Daughter one of her most critically and commercially successful novels. Later, in The Juniper Tree, she’ll complicate this unity by binding repeated objects to plot events to create a more complex story structure. But first, she’s got a few more heroines to follow.

I’m convinced that all we can do is what Comyns did: keep writing.Mr. Fox, Comyns’ fourth novel, tells the story of Caroline, a young single mother in London attempting to survive WWII with her daughter Jenny. While Caroline struggles against her relationship with the charming yet dastardly Mr. Fox (a funny, red-bearded brother to Bluebeard), she undertakes a series of odd jobs and side hustles to support herself and Jenny. Throughout Mr. Fox, Comyns is nudging towards a firmer grasp of tension and structure. Here, we see it as repetition. Comyns revisits three central motifs over the course of the novel: Mr. Fox looking like a fox, Caroline dreaming of escape and anticipating “something wonderful.”

There are other minor repetitions—Caroline is, not surprisingly, drawn to color and texture and furniture—but these seem less tied to the outcome of the story. They are evocative, but incidental. Decorative, but not fundamental. Some devoted Comyns fans might argue that the decoration is the foundation in her novels, but at least in the case of Mr. Fox, the decoration is not essentially linked to the plot outcome.

As much as I love Mr. Fox, I’m not sure it represents the height of Comyns’ craft achievement. Like The Vet’s Daughter, Mr. Fox reads like a long novella. It is stirring and straightforward. What was in her previous novels simply a mastery of voice and mood is here an evolving understanding of how those elements—so seemingly artless in Comyns’ hands—can also carry some of the requirements of plot, motif, and symbol. But the slightly more complicated structural demands of a novel—a subplot here, a minor character there—are absent in Mr. Fox. There are the three central motifs, but, in terms of a comprehensive system of object and image, or the deployment of symbols to build tension, we don’t have so much more than that.

Of course, the book has a great deal more content. There are lovely descriptions of furniture and gripping passages about air raids (really my favorite of any wartime passages I’ve ever read), but they’re not studded with any essential symbols or associations that would strengthen or complicate the novel’s affective climax. We feel relief when Mr. Fox dies, though it’s perhaps not the most nuanced relief. Which is not to deride what Comyns has made, only to observe that it has the tight concentration of a novella, not the complex sweep of a novel. Maybe this is just quibbling—you say novel, I say novella—but putting aside the niggling of taxonomy, we still have a book that isn’t quite as structurally ambitious as The Juniper Tree. We still have Comyns finding her footing.

In all of Comyns’ first-person novels, there is a female narrator who fits a certain mold. She thinks in long sentences. She observes the world with an effortless defamiliarization. She is not commanding. She is charming. She is funny. She is harmed by circumstance. She is abused by men, and sometimes women. She is poor. She is unprotected. All of these make for excellent plot starters, and in fact provide the precise social conditions that give rise to magical thinking—a lack of any real social or political power, or the means to obtain them.

Comyns’ women often have no recourse other than fantasy. The rare narrator who does achieve sovereignty, such as Bella or Caroline, does so by evading or rejecting her assigned fantastic destiny. A bomb kills Mr. Fox and only then can Caroline escape the weighted dread of being stuck with him or another man. A lid falls and kills Bernard’s son, and only then can Bella begin her own life, apart from the fairy tale that would limit and confine her. The book with the most explicitly magical realist ending—The Vet’s Daughter—leaves Alice with no other recourse than to fly away. Alice is young, Comyns isn’t as far along in her writing or thinking, and there doesn’t appear to be any other means of escape other than the fantastic. Comyns isn’t just exploring fabulism, she’s banging her head (or her narrators’ heads) against a tradition and a way of thinking about the world that was the most obvious option for the dispossessed half of humanity.

Maybe that’s a digression, or maybe it’s a critical part of Comyns’ aesthetic development. She couldn’t command the structural development that we see in The Juniper Tree until she could truly apprehend, and even reject, her own spot in her fairy-tale heritage. The more Comyns wrote, the more skilled she grew in using images for specific purposes—to build tension, to create a certain final feeling, to structure the reader’s experience. And, likewise, the more control she exerted over her stories, the more control her narrators could exert over their own fates.

It’s a fun thing to rummage around in a writer’s work, finding patterns, discerning various routes to success. There’s a danger to it, too, a smugness that comes from perching oneself above rather than within another’s work. Who doesn’t like to follow the crumbs of history and biography to make a story out of other stories? It feels good to package knowledge so neatly, to diminish the vital life force of a book into a step along the way, to render it ours and not, essentially, its own thing. Where then to go with these conclusions, potentially smug or even wrong? How can we make any biographical or formal knowledge of Comyns’ writing useful to our own books, things that we presumably want to keep alive rather than dissect?

I’m convinced that all we can do is what Comyns did: keep writing. Sure, it’s worthwhile to think about how exactly her work evolved, how she explored and refined her chosen genre, how she made mistakes and wrote her way through them. We could even sketch a formula for Comyns’ success: write your autobiography, write it again, distance yourself, modulate your tone, calibrate your narrative distance, and then, finally, arrange your symbols and associations so that they support a sturdy narrative structure.

It sounds so easy from afar, perhaps all theory does, but it doesn’t help us when we sit down to a blank page and a gaping inheritance. Maybe then it’s all in the timing. Later we can follow Comyns and revise our way toward our own better fictions, but for now it’s best we forget. Forget the exhortation to balance life and art, to use symbols judiciously, to integrate structure into that most essential element of autobiography: voice. Forget all these ramblings. Let them seep into some writerly subconscious and grow over with ivy, with juniper, with mistletoe. With all the mess of life that comes before the song: Kywitt, kywitt, what a beautiful book am I!