The Life and Death of a Cutting Edge Literary Journal, c. 1989

Kurt Hollander on Publishing The Portable Lower East Side

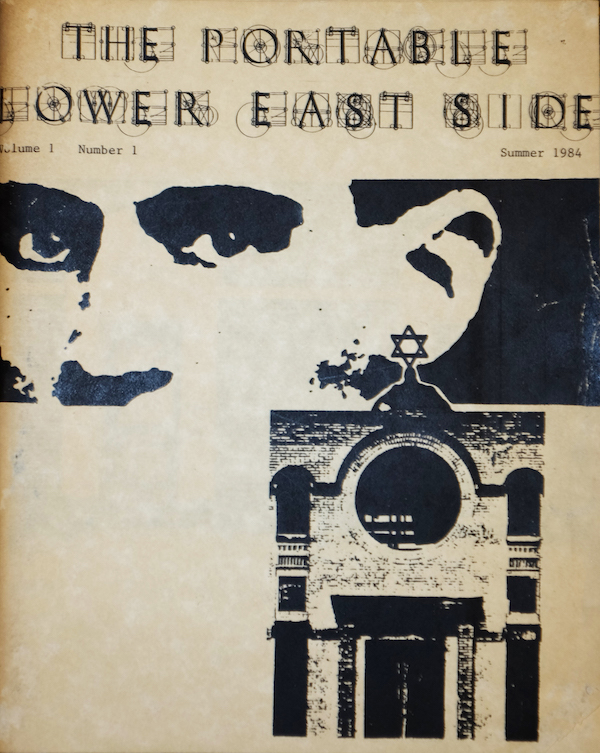

My mother passed away in 2021. I flew up to NYC from Cali, Colombia, where I’ve been living for the past seven years, to clear out her apartment. Not only had my mother saved early photographs, stories written on my old typewriter, and published texts of mine, she had also kept in her closets several boxes of different issues of the Portable Lower East Side, a literary and arts magazine I founded in 1983 with two issues published a year up until 1993.

Without anywhere to store them, and not wanting them to end up in the building’s trash compactor, I wheeled several boxes of the past issues in my mother’s creaky laundry cart over to Printed Matter, a bookstore on St. Mark’s Place that specializes in neighborhood publications.

The people at the bookstore had never heard of the magazine before (most were born after the magazine was founded) but were pleasantly surprised to see in the table of contents so many names of writers, photographers and artists they recognized, and offered to stock as many issues as I had and to give them a nice display. Although not a complete collection of the 14 issues of the Portable Lower East Side (I myself only have a single copy of the first issues), the copies at Printed Matter represent one of the most comprehensive collections of the magazine anywhere in the world.

The issues on display in the store (and online) are last-century relics of a lost culture, artifacts from 30 or 40 years ago that, although they were created in the same neighborhood where they are now displayed, are strangers in a strange land. A couple of the contributors still live in the neighborhood, but mostly they, like myself, have long moved on (I moved to Mexico City in 1989, fleeing the high rents and gentrification of the neighborhoods I had so loved).

Like many people, I got into the world of publishing (albeit, a very marginalized corner of that world) with the dream of becoming a well-known and respected writer. At the time I came up with the idea of publishing a magazine, however, I pretty much knew that my own writing would never be published in larger circulation magazines, such as The New Yorker, not because the writing was not great (it was not) but because it was not their brand of uptown, upper-class, upbeat writing. When I started publishing the Portable Lower East Side, downtown was still a literary liability.

The Lower East Side has long been home to waves of immigrants from all over the world, who from the start were excluded from and exploited by the mainstream economy of the city. Exclusion, however, gave rise to alternative, politically charged cultures, which defined themselves in opposition to mainstream culture and to American politics. The ghettos of New York City, while being centers of crime, drugs and violence, have also long been the most culturally rich and diverse places in NYC. The Lower East Side, one of the most densely populated urban centers on the planet for over a century, with one of the most diverse mixes of people from all over the planet, was truly unique.

Although I had grown up in Greenwich Village and had gone to public schools there and in Chelsea, the Lower East Side was where, beginning when I came of age, I went to buy books, see movies, drink cheap alcohol, and play pool. The neighborhood had been home to my parents when they got married (Avenue B and 2nd Street) in the 1950s, home to my father’s lithography workshop (Chrystie Street) in the 1960s and 70s, home to my father when my parents got divorced (Tompkins Square Park West) in the early 70s. It became my home when I first moved out on my own (Ridge Street just below Houston) in the late 70s.

The texts and images within the covers of the magazine represent inhabitants, spaces and lifestyles of the 80s and early 90s that are no longer to be found in the city.

I got the idea of portable from Penguin’s series of writers and also for the smallish size, but the name fit perfectly for what would become a series of illegal sublets all over the Lower East Side where I lived while publishing the magazine. Portable also referred to the gentrification in the neighborhood which began in the 1980s and displaced working-class, non-white communities to the outer boroughs. Gentrification was the beginning of the end of over one hundred years of the Lower East Side as an immigrant neighborhood, and it gave the magazine’s essays, fiction, photography and artwork its urban, oppositional focus.

The Lower East Side was where I started to write and what I wrote about. Most writing about the Lower East Side being published in the mainstream and even so-called independent literary world when I began the magazine in the early 80s (and long before that, as well) was written by uptown, suburban or mid-American white people who had moved to the big, bad city to make a career for themselves. Locals, on the other hand, especially immigrants or the children of immigrants, had no desire to use the neighborhood they had grown up in as an exotic, dangerous backdrop just to make a name for themselves.

The “hip” mainstream publishers and the “hip” literary magazines that were being published at that time in NYC featured gothic or exotic tales of the horrors of urban life. Much of this “hip,” contemporary fiction borrowed from the classical structure of the tourist-in-hell, in which the protagonist, from good society, sinks into the depths of debauchery and vice within the poorer, immigrant neighborhoods where their rectitude is tempted and perverted by prostitutes, gays, drug dealers, and criminals, but who eventually return to the light to tell their tale.

The fact that Manhattan is divided into uptown and downtown (with the Upper East Side being the wealthiest and whitest and the Lower East Side the poorest and most ethnically diverse), has led many a writer to employ such a heaven and hell structure in their novels, with all the moral baggage that comes with such an artificial, real-estate-driven split.

In the 1980s, at the same time as gentrification was whitening downtown neighborhoods, yuppie realism became a huge market success and writers from suburbia living the downtown life were sold as authentic punks and hipsters to a US and European mass market, thus fueling further gentrification.

Within NYC, however, there have always been dozens of self-contained, local communities, each large enough to provide a public for its own culture. These publics, whether they be Haitian, Hasidim, or Harlem drag queens, have their own magazines, radio programs, and dance halls, and are in no way dependent upon mainstream, white, upper-class media for their existence.

Except for the occasional appearance in the footnotes of a few academic studies, the Portable Lower East Side was not heard from again.

Way before the term multicultural was coined, the Portable Lower East Side was publishing writers, artists and photographers from communities outside the mainstream culture of the city, translating works of writers never before published in English, and revealing just how international NYC really was.

The term international in mainstream NYC culture inevitably meant European. The truly international New Yorkers, such as Asians and Latin Americans of longstanding, however, were viewed as minorities. There was a cultural Monroe Doctrine that welcomed foreign writers and artists as part of “America’s backyard” culture, while refusing to recognize those on its front stoop. Nuyoricans from Spanish Harlem or Loisada, for example, were never published as internationals but they also were never gringo enough to be considered American writers.

To counter this cultural gap in publishing, I began publishing a series of international issues focusing on specific, local cultures. The first issue of this series was on Eastern Europe (1986) and included writers and artists from the old country alongside those living in NYC. The second of these issues was Latin Americans in New York City (1988). Instead of featuring the magical realist writers from South America promoted in Europe and the USA commercial publishing world, this issue featured writing (some published bilingually) from the most vital Latino communities in NYC, especially Puerto Ricans, Dominicans and Colombians. I then began a series of guest-edited issues, including New Asia, New Africa and Queer City, for which I brought in editors from these communities and gave them free rein to choose the work they saw fit to publish.

From the beginning, the Portable Lower East Side mixed short stories, poems, essays, photographs and artwork, always within the context of NYC, focusing on the city from as many different perspectives as possible. Parallel to the international issues, I began a series of theme issues (Songs of the City, Crimes of the City, Live Sex Acts, Chemical City and Sampling the City), which included writing, photography and art work by people personally and politically involved in sex, drugs, crime or music, and not just writers or popularizers of such practices. This included the work of porn stars, Salsa musicians, political dissidents, punks, AIDS activists, trans people, junkies and cop killers. If this is considered outsider writing, then it’s outsider writing from an insider perspective.

I filled the first couple of issues of the Portable Lower East Side with my own writing and photographs, with writing from my mother and close friends, and with a lithograph centerfold drawing by my father of Tompkins Square Park (which he colored by hand).

While studying sociology, philosophy, and literature at the CUNY Graduate Center, I met and published work by fellow students, including Lynne Tillman, and my sociologist professor’s wife, the artist Marie Annick-Brown. I then spent three semesters at the newly created creative writing program at CCNY (where I also became an adjunct professor of World Literature), and where I published in the Portable the work of students and of my professors, including Grace Paley (and her writer husband Robert Nichols), Mark Mirsky and Frederic Tuten, all whom lived in and wrote about downtown NYC.

Having grown up in Westbeth, a low-income artist housing on the riverfront of Greenwich Village, where my mother still lived, it was easy for me to get neighbors to submit work. This included an epic poem on Yiddish-speaking socialists of the Lower East Side by Ed Sanders (one of the editors of the early 60s mimeographed magazine Fuck You), black-and-white photos taken while riding around the city in a police patrol car in the 1970s by Leonard Freed, portraits of city folk by Evelyn Hoffer, and the groundbreaking study of NYC real estate in 1971, titled Shapolsky et al, Manhattan Real Estate Holdings, by Hans Haacke, of which I updated the Lower East Side properties with info and photos and then published it as an accordion centerfold.

With past issues in hand, I felt increasingly emboldened to ask writers and photographers I didn’t know to contribute. The Manhattan White Pages was a literal who’s-who of local creators, listing everyone’s phone number and address, but just hanging out on downtown stoops, and in bookstores, movie theaters and bars, gave me access to many local creatives.

Downtown NYC in the early 80s was the greatest innovator of new music (rap, punk, Salsa, No Wave) and I took full advantage of all the local talent. I befriended Willie Colon, one of the creators of Salsa, and he not only translated into English his hit Tiempo pa’ matar for the first music issue, he also wrote a piece specially for the Sampling the City issue about growing up in the Bronx called “The Rhythms.” I also published writing from other musicians living in the city, such as Henry Fiol, Chico O’Farrill, Le Shaun, Johnny Dynell, Tuli Kupferberg, Arto Lindsay, Thurston Moore, Marc Ribot, and Richard Hell.

I basically turned my back on the prudish and provincial, gentrified and globalized literary and cultural world of NYC.

I also made a point of meeting and publishing the writing of some of the greatest, yet still marginal, writers such as Hubert Selby, Herbert Huncke, Jessica Hagedorn, Margaret Randall, Darius James and Larry Mitchell, and foreign writers who had spent a good amount of time in NYC, such as the Cuban anthropologist Miguel Barnet and the Hungarian novelist George Konrad, both of whom I had the pleasure of becoming friends with and visiting in their hometowns. Contributions by geographers, art critics, historians, sociologists, and political artists provided the context for the cultural and gentrification wars that were going on at the time in the neighborhood.

Just as importantly as the writing I published, was the writing I rejected, including the pseudo-experimental, punkish, pretentious, gothic and post-modern writing that was making a name for itself by making a mockery of my neighborhood and furthering the interests of real estate developers and condos. I also rejected some sappy poetry by Ric Ocasek and have never once regretted it.

From the beginning, photography was an essential element of the magazine. I got permission to publish historic photos of downtown by Weegee, Jacob Riis and Bernice Abbot from the New York Public Library and other local photo archives, and included known and unknown local contemporary photographers alongside these historical images. I published photographs by and became good friends with Robert Frank, who generously allowed me to publish an image of his of the Manhattan Bridge on the cover of the 1989 issue, at a time when he had published his work in very few other magazines, and by Nan Goldin, Dawoud Bey, Annie Sprinkle, and Anna Mendieta, as well.

The first few issues of the Portable Lower East Side featured ads for local businesses, including Shapiro’s Kosher Wines, Yonah Shimmel’s Kosher bakery, Russ & Daughters, El Castillo del Jaguar (a Dominican diner), Christine’s, Veselka, and Teresa’s (three Polish restaurants in the East Village), DeRoberti’s Italian Pastry Shop, St. Mark’s Cinema, Neither/Nor, St. Mark’s and the East Side Bookstore, and the Taller Latinoamericano, a Latin American cultural center and Spanish school (where I studied with the director, Bernado Palombo, a former Young Turk and songwriter for Conjunto Libre, of which I published the song Imágen latina).

Each ad included a photograph I took of the facade of the business on one side of the page and their business card, logo or information on the other side. The ads not only helped defray the costs of buying the paper the magazine was printed on, but the images of the facades of these local businesses were published alongside photographs taken by local contemporary and past-century photographers, as they both provided visual documentation of a dying working-class culture. In later issues, I also included ads for Granta, October, and Semiotext(e), magazines with whom my magazine shared certain intellectual affinities (though not their academic language or uptown elitism).

I started the Portable Lower East Side when I was only 23, at a time when I knew next to nothing about magazines or publishing, although I knew something about my neighborhood and about how to hustle. I typed up the first issues on an electric typewriter, photocopied page by page late at night at an office where my girlfriend worked, did the artwork and took photos for the covers myself, and held collating and stapling parties with family and friends to put it all together.

At that time I was not aware of samizdat (self-published banned books or magazines retyped illegally and circulated by hand in the Soviet Union and Eastern Europe), although all DIY publishing shares similar techniques. I distributed the first few issues myself, carrying dozens of copies in a knapsack on my back to bookstores all over the neighborhood.

“Some will be offended, but this groundbreaking volume’s artistic merit is indisputable.”

I met Kim Spurlock, originally from Southern California, at the party I threw for the second issue, and he offered to help design and print the magazine (for free!) starting with the third issue, something which upped its quality and esthetics enormously. Kim designed the logo of the Portable (the silhouette of a suitcase with a tenement building, complete with a water tower and smokestacks, inside), and he designed the covers and the insides of the next few issues, making the magazine even smaller and more portable. I would go stay with him in his house in New Jersey for a couple of days and we would surreptitiously go to the print shop where he was working late at night and print up whole issues (I supplied the paper and inks).

After having published several issues, I started applying for and getting grants, which helped pay for the printing and allowed me to pay a minimal fee to contributors and/or guest editors. Getting grants pushed me to be more professional, and the magazine began to be distributed to bookstores all over the USA, and the magazine even began getting subscriptions from universities and museums.

One requirement to apply for grants was to have an editorial board. To comply, I invited John Oakes (publisher of Four Walls Eight Windows), Susan Willmarth (in charge of magazines at the St. Mark’s Bookstore), the writer Lynne Tillman, academic Tricia Rose, Beat editor Don Kennison, David Unger (the director of CCNY’s Latin America department), Gregory Kolovakos under the pseudonym Rod Lauren (as he was the director of NYSCA’s literature program), literary agent Ira Silverberg, poet Marithelma Costa, writer and sex activist Veronica Vera, and other friends and associates, with get-togethers where I would pump them for ideas while plying them with food and drink.

Publishing parties were an essential element of the magazine. I held one party, with readings by contributors, at the Gas Station on Avenue B, for the Latin Americans in NYC issue; another at my house for the Asian issue; at Frankie Dynell and Chichi Valenti’s Clit Club in the Meatpacking District; Bullet Space for the Crimes of the City issue; and at ABC No Rio (I hired an all-female samba band to get everyone dancing that night).

Throughout the years of its existence, and despite my best efforts at promoting it, there was almost no mention of the magazine in the media, that is, until one day it wound up in the headlines on the front page of the New York Times and Washington Post. Although the Portable Lower East Side focused on life and culture in NYC, it got caught up in a national scandal involving the National Endowment of the Arts.

In February 1992, Representative Dick Armey, a Texas Republican, and Donald Wildmon, director if the American Family Association in Tupelo, Miss., sent excerpts from the Live Sex Acts and Queer City issues to all members of congress and to then-president Bush, claiming they contained obscene and blasphemous material. The material they referred to were two photographs by Nan Goldin showing a man before and after masturbating, a line from a poem by Sapphire about the Central Park rape of a white woman jogger which mentioned Christ in the same line as masturbation, and my transcription of pre-recorded phone sex (“Dial 1 for oral sex, 2 for anal sex…”).

After he was attacked by various congressmen and by Patrick Buchanan (Communication Director for George Bush) for funding my magazine, John E. Frohnmayer, director of the NEA, defended the “literary merit” of the magazine’s contents and complained that the contents at issue “were taken out of context and sensationalized.” This was, he later wrote, “the precipitating event of my firing.” Buchanan declared that Frohnmayer’s defense of the magazine has been a “mistake,” and added: “None of us likes to consider ourselves aesthetic hicks, but it’s very hard to explain why federal money went into Queer City.”

To fight this unjust attack on my magazine, I sent out an op-ed piece that I wrote entitled “A Pinhead View of Literature,” refuting the accusations of blasphemy and obscenity by politicians. I sent it to The Village Voice and other so-called liberal media, but none were interested and none wrote anything in defense of my magazine. The Nation, however, published a piece about the NEA scandal in which it called Live Sex Acts and Queer City pornography (my transcription of pre-recorded phone sex really offended them). When I sent a letter to the editor complaining about their treatment of my magazine, they published a letter from the editor about how I had attacked them in my letter (which they didn’t even publish!).

Because of the scandal, Sapphire received a three-book, six-figure contract with a commercial publisher, and Nan Goldin got some good press exposure. The Portable Lower East Side, on the other hand, had its yearly funding retroactively nullified and I was forced to return the grant money I had received from the NEA, money which I had already spent on the two issues.

The scandal showed me how US mainstream and so-called alternative media functioned: the sensationalist soundbite dominated, attention was focused mostly on a single line of poetry and two images without any mention of the other contents of the issues. The history and editorial direction of the magazine itself was completely ignored, this despite the US Supreme Court’s definition of obscenity stating that a work must be judged in its full context. Had they looked closer at all the previous issues, the pinheads in congress and the anti-sex puritans in the liberal press would have found a lot more that was objectionable to their sensibilities, being that the magazine had always been dedicated to opposing mainstream US politics and culture and to offending good liberal and literary taste, as well.

When Bill Clinton was elected president and a new director of the NEA was appointed, the Portable Lower East Side was awarded a grant for the following year, plus one year of back support added to make up for the money that had been taken away, thus vindicating the magazine from any real obscenity charges. I published a couple of more issues, Chemical City and Sampling the City, two of the best issues, but then closed up shop.

I managed to get an anthology of the Portable published by Grove Press two years later. The book, entitled Low Rent, A Decade of Prose and Photographs, was my first experience with a commercial publisher and I had some hopes that it would make a bit of a splash, especially after it received very positive reviews in Publishers Weekly and Kirkus Reviews, which said: “Some will be offended, but this groundbreaking volume’s artistic merit is indisputable.”

When the anthology got a negative review in the Village Voice Literary Supplement by a reviewer who not once mentioned the magazine behind the anthology and who obviously felt “offended,” the anthology went nowhere. After that, I basically turned my back on the prudish and provincial, gentrified and globalized literary and cultural world of NYC (which was easy being that I had already made a life for myself in Mexico City and was already editing a new art magazine of the Americas).

Except for the occasional appearance in the footnotes of a few academic studies, the Portable Lower East Side was not heard from again. Having been published before words and images became digital data, the magazine was never an inhabitant of the Internet.

Opening the closet doors in my mother’s apartment and hauling out the dusty boxes full of unsold copies of the Portable was like uncovering a time capsule from decades past. Each issue was an artefact of writing and images from and about a city that has in large part disappeared, having undergone radical transformations in its demographics caused by gentrification and by globalization.

The texts and images within the covers of the magazine represent inhabitants, spaces and lifestyles of the 80s and early 90s that are no longer to be found in the city, and bound together in each issue they represent a virtual neighborhood of family members, friends, acquaintances, and fellow cultural and art workers, all of whom offer their literary, artistic or critical perspective on life in what, for me at least, was still the greatest city on earth at that time.

Kurt Hollander

Kurt Hollander is a writer and fine art/documentary photographer. Originally from downtown NYC, Kurt lived for over 20 years in Mexico City and has been living in Cali, Colombia since 2013. He is the author of Several Ways to Die in Mexico City (Feral House, 2013), writer and director of the feature film Carambola (Mexico, 2005), and was the editor of Poliester, a contemporary art magazine of the Americas, from 1993-2000. This text is part of an unpublished collection of autobiographical essays entitled From Downtown to El Centro. https://linktr.ee/