For the first days after my husband Hal was diagnosed with pancreatic cancer, I was convinced it was my fault. That all those years of wishing he would leave me led to this. That all my inadequacies as a wife, as a partner, had made him sick. That the rage I’d caused in him had hardened into tumors.

I was the cancer. I was the metastasis. I was the Wicked Witch of the West.

Except the house fell on him instead of me.

*

I started cheating on Hal within two years of being married. I never thought I would stay but I didn’t know how to leave. We had a baby. I didn’t want to split custody of our child. So I left in other ways.

I felt no shame. I had convinced myself that the only way to live truthfully was to be myself in private.

One cannot be judged by her truths unless she shares them aloud, and a liar is so much safer, so much easier to love. So I buried my secrets like treasure in the backyard. Way out by the fences I pretended I didn’t know how to climb. The problem was, I forgot to eat the map.

I don’t know if it was the first time he went through my email. I do know that, nine years into our marriage, he finally found what he was looking for.

I wasn’t home when Hal opened my computer and went digging in my drawers, but I imagine what he must have looked like—his fingers on my keys, face pressed against the windows of words intended for someone else.

When he rang my phone to call me out, I was on set standing on an apple box, moments away from delivering a baby food–sponsored monologue, smiling into a camera like the whore he would say I was later. Reading off the teleprompter, pretending to be a good wife to an audience of strangers.

“I know everything. I read everything,” he screamed. “And I’m leaving. When you come home, I’ll be gone . . .”

I scrambled to turn the volume down on my phone, assuming that everyone could hear him. And then, before I could respond, he hung up.

“Rebecca? Is everything okay?”

“Yes. Everything is fine,” I said, before delivering the monologue to the camera—my smile, a smear of saccharin.

I’m just a lying liar who tells lies.

And the show must go on.

*

We decided to marry in Vegas because that’s where liars who don’t want to get married get married. It’s where newly pregnant, barely adult women stand in line with other newly pregnant, barely adult women. It’s where gamblers say “I do.” In Vegas, a wedding is a song lyric, a punchline, a double dare.

My internalized bitterness became a passive aggressive time bomb.

Not a single person was invited to our wedding. The big-haired receptionist guest starred as our marital witness. She smelled like baby powder and cigars. “Y’all from around here?” she asked upon signing us in. I don’t remember where Hal said we were from, but I know it wasn’t true. He was a liar, too.

A Vegas wedding with no witnesses is like a tree falling in a forest—no one there to hear it make a sound. Without witnesses, it felt like our wedding was pretend. That we were just a couple of people who ran away for a weekend and then came back with matching tattoos.

If a father isn’t there to give his daughter away, does that mean she gets to keep herself?

I was five months pregnant when we exchanged vows on the stained carpet of the Little White Chapel. I wore gray pants and an off-white maternity shirt covered in flowers with a pair of sleeves that opened wide as mouths. My something-borrowed was the baby in my belly. My something-new was the lump in my throat.

“In sickness and in health . . . till death do you part. I do.”

They pronounced us Mr. and Mrs. before he kissed the bride. But I was never going to be either of those things. Not a Mrs. and certainly not a bride.

I hated every minute of our wedding. I found out later that Hal did, too, but for different reasons. He wanted a real wedding with real flowers and real people we knew as witnesses.

When I married Hal, I chose to keep my father’s name over his, but only because it was my mother’s name, too. Woolf had become me. She was the only Rebecca I knew.

We made a compromise. The child I carried would have his name so that I could keep mine.

Going along with things I disagreed with was an integral part of my marriage, but only because it was how I’d learned to be loveable in my formative relationships. Boys always liked me because I did all the things they wanted girls to do.

Because agreeable girls become lovable women. All you have to do is say yes.

But over the years, the shift became seismic. My internalized bitterness became a passive aggressive time bomb, and by the time our twin daughters were born, I was furious with myself for not fighting harder for our daughters to take my name. Wasn’t that fair? For our son to take his father’s name and our daughters to take mine?

It mattered to me more than almost anything. How could I raise my four children to be patriarchal rule breakers when their very names were yet another example of a wife placating her husband? Another woman who cosigned for the erasure of her lineage because of some antiquated patriarchal rule?

“Then just change their names already! If it means this much to you, just go change their names.”

But I didn’t and I wouldn’t, and he knew that, too. I would never change my children’s last names for the same reason I would never change mine.

And yet the moment I knew he was dying, the moment he called me from the ER the day before his forty-fourth birthday with the stage four cancer diagnosis and “Bec, this is it. I’m going to die . . .” The moment I hung up the phone, I had one thought: I’m so glad our children have his name.

*

“This is the wrong juice, Bec,” Hal snaps, recoiling at the taste. He’s drinking out of a Dixie cup with a blue monster on the side.

We have been back and forth between home and hospital so many times I’ve stopped counting. I have a garbage bag full of discharge paperwork under the bed as proof.

In order to come home—to stay home—Hal insists he needs everything that is available to him at the hospital to be in our house, including the juice boxes the nurses mix with his constipation cocktail. Ocean Spray green-apple juice in tiny wasteful boxes mixed with MiraLAX. Cold. But not on ice.

It’s the same with the straws that bend at the tops and the chicken salad he orders from the hospital cafeteria.

When we are home, everything I do is wrong. Even when I do everything exactly like the nurses told me, taught me, walked me through with pen and paper multiple times. I understand why. I will survive this and he will not. I am fine with being a punching bag. Welcome it, even. It makes me feel less guilt for having a healthy, working body. For knowing that I am the one who, goddess willing, will see our children off into adulthood. I am the one who can stay and I am sorry. So sorry.

“You’re doing it wrong!” he screams at me as I pull the plastic sleeve over the chemo port in his arm in preparation for his shower. “Just stop! Don’t even bother! I want to hire someone else to do this.”

The day the homecare worker comes to bathe Hal, he fires her before she can grab the soap. Seated naked on the shower chair, clutching the plastic sleeve over his port, he tells her to “get my wife and go home.”

*

As a teenager, I was the cool girl. Not because I was cool, but because I let the boys do whatever they wanted and thanked them for it. They could talk shit about girls in front of me and do things to my body and ask me for favors and I always said yes and like, totally, for sure. I cooked and cleaned and drove them around in a car I filled with my own gas money. I was the hole in which to bury secrets, desires. I was free therapy. A sex worker who didn’t need to be paid. Worse, there were many times—too many to count—when I paid them. “Oh, you’re low on money? No problem. This one’s on me.”

I protected them. Stuck up for them. Got them job interviews. Helped with their homework. Told them to call me if they needed anything. Always picked up.

This is nothing new, of course. We know exactly how to give it all away and then apologize when we give it away wrong. We amputate our arms when asked for a hand and are so very sorry for all the blood.

He knew everything and I knew nothing, and because he was so much smarter than I was, I believed him.

We are women and this is what we have been programmed to do for generations. Like taking last names without compromise. And being given away by our fathers at weddings. A platter passed between men.

“Can you please pass the meat?”

“Sure. Let me wrap her in lace first, because purity. Because virginal. Let me cover her face and mouth with white, because lamb.”

And yet, I have always cried at weddings even though every single one of them makes me want to stand up and scream NOOOOOOOOOOO.

At twenty-three, I didn’t know how to scream yet. I never wanted to be anyone’s wife, but one day I was going to be a mother and Hal was going to be a father and even though we barely knew each other, we got married. Because that’s what pregnant women are supposed to do. Because I loved him. And he loved me. And maybe that was enough. I assumed it was enough.

We loved each other madly, in those days—the way people do when they first meet. When the sex is insane, and everyone is still pretending. I knew how to be the woman he wanted me to be. I was passive and kind, thoughtful and generous. I cooked beautiful meals every night and fucked all morning. And he made me laugh. He was funny and charming, charismatic and sexy. He was confident and interesting and wild.

I was already pregnant by the time we had our first fight but didn’t know it yet.

“I don’t believe in art,” he had told me. “I believe in entertainment.”

“But I’m not an entertainer, I’m an artist.”

“Do you sell your work?”

“Yes.”

“Then you are an entertainer.”

Every time I opened my mouth, his voice got louder. It was the first time I remember feeling afraid of him. No one had ever talked to me like that and I froze. Did the thing that I would do a thousand more times over the next decade: swear to leave. But I didn’t. Instead, I said nothing as he went deeper into his monologue about art and commerce and why I was wrong. And when he was done, he immediately changed the subject. Like nothing had happened. Like everything was fine, moving on.

This fight would come back to haunt us repeatedly through our marriage. I was almost always wrong about everything, mainly how I perceived my work, my art, and myself.

He had opinions so strong his voice quaked. And every fight ended the same way: with him relieved to have gotten whatever he was ranting about off his chest. And me beaten the fuck down, alone in whatever corner of the room he’d left me.

He knew everything and I knew nothing, and because he was so much smarter than I was, I believed him.

__________________________________

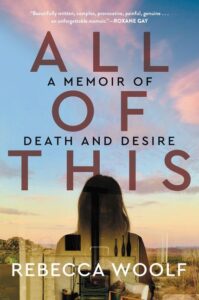

From All of This: A Memoir of Death and Desire by Rebecca Woolf and reprinted with permission from HarperOne, an imprint of HarperCollins Publishers. Copyright 2022.

Rebecca Woolf

Rebecca Woolf has worked as a freelance writer since age 16 when she became a leading contributor to the hit 90s book series, Chicken Soup for the Teenage Soul and its subsequent Teen Love Series books. Since then, Woolf has contributed to numerous publications, websites and anthologies, most notably her own award-winning personal blog, Girl’s Gone Child, which attracted millions of unique visitors worldwide. As well as launching her own successful blog, Woolf has contributed dozens of personal essays to publications both on and offline including Refinery29, Huffington Post, Parenting, and Romper and in 2012 hosted Childstyle, a web series on HGTV.com. She has appeared on CNN and NPR and has been featured in The New York Times, Time Magazine and New York Mag. She lives in Los Angeles with her son and three daughters.