“I had not been able to work in some months, had been paralyzed by the conviction that writing was an irrelevant act, that the world as I had understood it no longer existed,” she said. “If I was to work again at all, it would be necessary for me to come to terms with disorder.”

As she would write in the famous opening to her essay “Slouching Towards Bethlehem,” “San Francisco was where the [country’s] social hemorrhaging was showing up. San Francisco was where the missing children were gathering and calling themselves ‘hippies.’”

Taking their cue from the Doors, the baby boomers shouted, “We want the world and we want it now!” Didion was intrigued and appalled.

The most privileged, pampered, studied, and commercially targeted group in American history, the boomers were a massive workforce in the eyes of corporate executives. Madison Avenue saw a crowd of consumers. In order to channel their emergent desires, government agencies and medical boards tracked every twitch, blink, and speck of saliva. Behaviorists argued with psychiatrists who quibbled with law enforcement over the care and well- being of America’s kids. Biologists debated nature versus nurture, stimulus- response units, and organicism. The Woodworth Personal Data Sheet, Binet’s IQ test, Rorschach’s inkblots, the Thematic Apperception Test, the Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory, Dr. Spock, and Captain Kangaroo spoon-fed boomers daily doses of themselves.

Overfed, resentful of the poking and prodding, the children puked it all up. Many decided to go missing. And then they wanted more, but on their terms. The world had tried too hard to shape them. They decided to change the world.

The testers had failed to maintain control. They’d fumbled the testing tools. How had this happened? Didion wondered.

Perhaps the starting point was 1946: Persuaded by data sheets that the American populace was crippled with neuropsychiatric disorders, the U.S. Congress signed into law the National Mental Health Act, budgeting $4.2 million to study dysfunctions and to treat their manifestations through medicine. In this context—in tandem with the military’s aim to develop mind control drugs—two Bay Area psychologists, working with Oakland’s Kaiser Hospital, published a study arguing that mental patients receiving psychotherapy fared no better after nine months than patients getting no treatments; mood-enhancing drugs, then, might be a profitable area of research. The primary author of this study was a young man named Timothy Leary.

In this context, Max Rinkel, a psychiatrist at the Massachusetts Mental Health Center, ordered a shipment of LSD-25 from Sandoz Pharmaceuticals and dosed his colleague Robert Hyde to see what would happen. At the American Psychological Association’s convention in Cincinnati in 1951, Rinkel reported that Hyde had become paranoid on the drug, hearing imaginary doors slam shut.

In this context, the Rand Corporation as well as various Veterans Administration hospitals, conducted lab experiments with mind- altering drugs. In Menlo Park, California, Dr. Leo Hollister, recruited by the CIA for MKULTRA, administered psilocybin and LSD to a volunteer subject named Ken Kesey.

By now, it’s well documented that Kesey, Leary, and other pranksters let the goodies out of the bag. At least for a while, the lab men were no longer in charge of hallucinogen- based social experiments.

Old Hollywood was flashing: Cary Grant dropped acid more than sixty times. “I have been born again,” he said. Christopher Isherwood dosed himself under the direction of Dr. Sidney Cohen of UCLA and the Veterans Hospital in Los Angeles. Even Henry Luce tried the drug on a visit to California. He conducted an invisible orchestra on a lawn one night.

Aldous Huxley, a lifelong quester for the ideal intoxicant and the author of The Doors of Perception, from which Jim Morrison took the name of his band, died, on the day JFK was shot, believing he had found in LSD the key to the cosmos. He used a William Blake quote as the epigraph to his book: “If the doors of perception were cleansed everything would appear to man as it is, infinite.” He once told Timothy Leary that Western culture would experience a profound revolution in consciousness if “wisdom drugs” could be given to cultural “elites”—artists, economists, intellectuals—who would then disseminate their visions throughout society.

With the help of Kesey, Allen Ginsberg, Gary Snyder, Alan Watts (who praised drug- induced mysticism on his Bay Area radio show), the Grateful Dead, and pioneer outlaw chemists, primarily Owsley Stanley, Leary went Huxley one better. He dispensed “wisdom” on the streets at about two dollars a pop.

Cheap rents, the proximity of Berkeley, and state-of-the-art labs at nearby VA hospitals combined to make San Francisco’s once-blighted Haight Ashbury neighborhood a grand ballroom for mind expansion. “People are beginning to see that the Kingdom of Heaven is within them,” Ginsberg said. “It’s time to seize power in the Universe, that’s what I say . . . not merely over Russia or America—seize power over the moon—take the sun over.”

For Didion, who had never marched to the Beats—or the hippies, as the press tagged them, playing off Norman Mailer’s term hipster, youngsters wearing flowers in their hair up and down the Haight—the Kingdom of Heaven was not nigh in psychedelic shenanigans. For her, this epic experiment, under no one’s supervision, was closer to William Carlos Williams’s warning in his introduction to Howl: “Hold back the edges of your gowns, Ladies, we are going through hell.”

* * * *

The essay “Slouching Towards Bethlehem” probably began as a series of discussions with Ted and Shirley Streshinsky. “After Delano, we saw Joan and John in the Bay Area,” Shirley said. “I suppose the idea for a story on the subculture was talked about, because either Joan or Ted, or perhaps both of them, proposed the story to The Saturday Evening Post. Our friend Paul Hawken, who was very much part of the beginning of the hippie movement, had something to do with it. He was the son of one of Ted’s good friends, and during that period spent a lot of time at our house and convinced Ted that the counterculture movement was worth a story.”

Like Didion, Paul Hawken was a fifth- generation Californian. In time, he would become a wealthy entrepreneur, selling macrobiotics and “gentleperson” gardening supplies. He established the Erewhon Natural Foods store in Boston, helped Stewart Brand publish The Whole Earth Catalog, and became a political adviser to Jerry Brown and Gary Hart. In the mid-1960s, he was living in the Haight with his friend Bill Tara, promoting theater and rock concerts in an old fire house on Sacramento Street, just north of the Haight, in the Sunset District. His specialty was light shows. He gave Janis Joplin and Big Brother and the Holding Company one of their first breaks, and he was an early supporter of Jerry Garcia and the Warlocks (later the Grateful Dead). At the time, he embraced the hippie “lifestyle,” but he was by no means one of the “missing children” Didion would emphasize in her essay. Like Chet Helms and Bill Graham, better-known local rock promoters, he was a budding businessman. “When everybody else had long hair, I cut mine off,” he said. “I’ve always been a contrarian.”

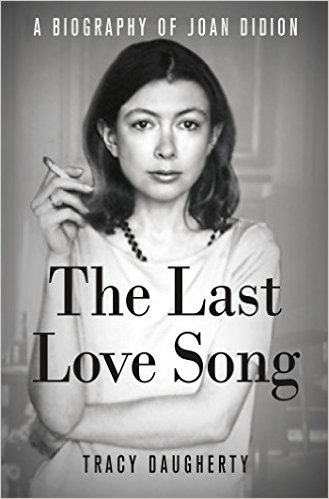

From THE LAST LOVE SON: A BIOGRAPHY OF JOAN DIDION. Used with permission of St. Martin’s Press. Copyright © 2015 by Tracy Daugherty.