The Last Days of James Baldwin's House in the South of France

Where Miles Davis, Nina Simone, Stevie Wonder and More Once Met

After my first sighting of Chez Baldwin in 2000, I traveled to other places important to the writer—from the streets of Harlem and Greenwich Village to Paris, to Istanbul, Ankara, and Bodrum—and met many people who knew him and shared living spaces with him, and who all confirmed his paradoxical need for a frantic nomadic lifestyle on the one hand, and, on the other, his fervent desire to establish a stable domestic routine in multiple locations. Intrigued by his late-life turn to domesticity as well as the increasing focus of his works on families, female characters, and black queer home life that are prominent in Just above My Head and The Welcome Table, I returned to Chez Baldwin in June 2014. By that time I had published a book on the writer’s Turkish decade and numerous articles about various aspects of his works.

I was not prepared for what I saw in place of the house that had been full of furniture, books, papers, photographs, and art when I first saw and photographed it. Now, I confronted an empty, disintegrating structure, virtually open to the elements, filling with vegetation and wildlife that had crept inside over the walls and windows. The back patio in front of the study, where Baldwin liked to take reading breaks at a round table under an umbrella, along with the brick and stone pathways through the garden were so overgrown with unchecked weeds that the crumbling structure of the house seemed to float on top of tall tan grasses swaying in the breeze. Full of sharp little burrs, this grassy expanse tugged at one’s shoes, attached its tiny hooks to fabric and straps, and scratched one’s skin as if attempting to deter movement. An occasional orange tree hung with bright fruit flashed amid the tangled greenery and dried branches, as if to recall the harmony between natural bounty and human husbandry that once existed here.

Outside the writer’s study, 2014. Photo by Magdalena J. Zaborowska.

Outside the writer’s study, 2014. Photo by Magdalena J. Zaborowska.

The writer’s study, on the ground floor in the back, where Georges Braque had once painted, and which Baldwin called his “torture chamber,” had broken shutters and windows, one missing glass entirely, and seemed especially exposed and pitiful. When I visited the house for the first time in 2000, the study had been rented out to pay for the upkeep of the house, and so I was only able to photograph its well-kept exterior. Now the interior not only was wide open to view but also nearly blended together with the landscape, the boundaries between wall and garden nearly erased, and the writer’s room had become a cavern that sported a fireplace filled with dry leaves. It seemed terribly significant that the very space that used to house the writer’s creative labors was the most porous and open to the elements, the most vulnerable and deserted. There were traces of transient visitors, or laborers sent by the owner, some of whom left plastic bottles and food wrappers scattered on the floor. The trash mingled with leaves, twigs, dead bugs, and rodent droppings, creating mysterious organic/plastic designs on the stone mosaic floor.

Baldwin’s study and quarters, 2014. Photos by Magdalena J. Zaborowska.

Baldwin’s study and quarters, 2014. Photos by Magdalena J. Zaborowska.

The contrast between the interior images, taken during my two visits, speaks to the sad fate of Chez Baldwin. Once inside the study, easily accessible through low, open windows, I noticed the melancholy progression of time marked by the vines snaking over the chipped-tile floors, marking trails with no beginning and end. That part of the house consisted of three rooms linked together that ended with a small modern bathroom. The space of what used to be the heart of Chez Baldwin, that inner sanctum of the study, felt so eerie while we wandered around it that my 12-year-old son, Caz, who accompanied me on that trip, picked up a rusty hoe he found in the grass outside and told me he intended to protect us with it, “just in case.” I tried to explain to him that the haunted feeling we picked up was simply that, a feeling our bodies generated, a normal sensation caused by the surroundings, a reaction to perhaps just a smidgen of guilt that accompanied our not-exactly-authorized visit to the property. I did have to engage in rather convoluted verbal gymnastics to explain to him that our entry was justified, indeed, was performed in the noble “interest of knowledge” and “for a good cause” of documenting a structure that might soon be gone.

As we wandered through the house and the grounds for over an hour, I found myself surprised by how emotionally fraught the confrontation between my past and present experiences of that space proved to be. I felt both sadness and anger that the house was let go by the Baldwin family following David Baldwin’s death, even though it was possible to hold on to it. I also felt frustration and despair about my own impotence to do anything, blaming myself for not having taken many more photographs in 2000 (who knew the house would be lost so soon?!), regretting that I never saw the writer’s study furnished and inhabited. I kept circling around the structure, photographing frantically, getting annoyed as my son nagged me to leave. So much needed to be done, preserved, and documented; so much had been lost already. The obvious reason behind all this turmoil was the painful fact that the only viable writer’s house for James Baldwin anywhere in the world was crumbling away before my eyes. It was not yet gone and could possibly be saved, but it was effectively out of reach of anybody who might want to preserve it by the sky-high price that real estate bidding wars had stamped on it.

Who could afford to pay 30 million euros for a writer’s house that was falling apart? Would it be bulldozed to provide space for shiny new tourist quarters or a rich man’s villa and swimming pool? Or would it be left alone, the lesser of two evils, waiting for the ravenous landscape to absorb the crumbling structure completely? By early November 2014, Jill sent me a distressed email and a couple of hastily taken photographs that provided glimpses of what was left of the house. Perhaps the reason why the first part of Chez Baldwin to go was the most vital—the writer’s studio and living quarters—had to do with razing to the ground any remnants of Baldwin’s tenuous hold on the structure. I was not there when it happened, but I feel as though I had been: the disturbed soil smelled moist and cold, richly brown, loamy, and mineral, the day overcast and solemn.

“The only viable writer’s house for James Baldwin anywhere in the world was crumbling away before my eyes.”

After Caz and I saw the house, we met the owner of the famed local restaurant and inn, La Colombe d’Or, Madame Pitou Roux. As we chatted in the foyer of her establishment, which Baldwin visited regularly, she told us that the state of Chez Baldwin was a shame and proof of the meanness and small-mindedness of those who wanted to capitalize on that property and drive away the memory of Baldwin. Middle-aged now, Pitou Roux knew “Uncle Jimmy” as a child, and she adored him throughout his life in St. Paul-de-Vence. She recalls having long conversations with him into the night when she was a young woman in her twenties, when she needed “life advice.”

I first spoke to her in 2000, and she was much more lively in her manner and hopeful about Chez Baldwin’s prospects at that time; her mother, Yvonne, was too ill to speak to me. She remembered her first sighting of Baldwin then, at the restaurant where we were sitting: he was so striking and charismatic, ugly and beautiful at the same time, that she thought he might have been one of Joan Miró’s drawings come to life. She cherishes his memory and continues to receive visitors and field their many questions. At the same time, by 2014, she seemed slightly paranoid about being recorded against her will. When we were about to leave, she asked Caz to unroll a hoodie he had been holding over his arm—“What do you have in there? Show me?!” She wanted to make sure we had not been spying on her; I was both disturbed and amused by this suspicion, while my son found it mean.

Madame Pitou Roux’s establishment, which in the past belonged to her parents, saw Baldwin on a regular basis and created its own set of memories and legends about him—his favorite chair at the bar, the entrance he usually took, the conversations that lasted into the wee hours of the night, the celebrities and artists who came to dine with him (Yves Montand and his wife, Simone Signoret; Miles Davis; Nina Simone; Caryl Phillips; Stevie Wonder; Bill Cosby). La Colombe d’Or has kept Baldwin’s traces safe in the stories and anecdotes of those few who still recall him (besides Pitou, there is an elderly waiter who seems to remember him well), but it does not display any mementos of him anywhere prominent, at least to my knowledge. This might not be a thing to do, since Baldwin frequented the place for the mere decade and a half that he lived in St. Paul-de-Vence, the period that now seems forgotten. His traces have been erased, for if you don’t know of his link to La Colombe d’Or, you are not likely to discover his face peering at you from photographs on the wall; a random guest will not be prompted to ask, “Who is that man?”

While at Baldwin’s house this time, I took as many digital photographs as possible of what was left of the property. When I ran out of space on my card, I shot more, even video, with my iPhone. I found myself obsessively tracing the progress of the damage since my first visit, though it seemed a hopeless endeavor. For example, I discovered that the gorgeous frescos that once adorned the stairwell ceiling were gone, plastered over and whitewashed, most likely due to a repair of the leaky roof. The slightly damp air, occasional creaking of shutters, and swishing grasses and weeds outside amplified the melancholy nature of my labors.

The ceiling in 2000 and 2014. Photos by Magdalena J. Zaborowska.

The ceiling in 2000 and 2014. Photos by Magdalena J. Zaborowska.

When I returned to the site of Baldwin’s house in June 2017, its remnants were hard to see from the street. The developer who owned it, and had had two-thirds of the structure bulldozed in 2014, erected large, colorful billboards advertising soon-to-be-built luxury villas clustered around an expansive swimming pool. The ironic name of this new incarnation of the famous writer’s house and garden was to be “Le Jardin des Arts”; the sales were held by Sotheby’s and advertised 19 “grandly” chic apartments with “a panoramic view of the sea,” urging potential buyers to “reserve yours now!” Behind a new, locked, black metal gate stood the gatehouse, stripped of its hot–pink flowering vines and carelessly transformed into a real estate office for those who could afford the best views of the Mediterranean. It was segregated from the main house by a huge billboard sporting the image of the future swimming pool, with the inevitable couple of frolicking vacationers in the water. A cleverly camouflaged door inside that image led to the site; Chez Baldwin’s diminished façade, only partially visible behind it, appeared blackened, as if by smoke.

We did not enter the site through that glamorous door, but via a gap in the fence we reached through an alley to the right, which was discovered by my 15-year-old son. Hoping that no one would see us from the gatehouse/office (this time, there were signs prohibiting entry and confirming surveillance), we circled the property and took many photographs of what was left of Baldwin’s once lush abode. Reduced to its core central part, which now towered three stories high, the crippled building—soon to be a pool house—bore imprints of demolished rooms on both its sides, with the left one still bearing remnants of the tiled bathroom wall from Baldwin’s downstairs study, and of the kitchen that had been located above it. The site was mostly stripped of its vegetation, with a lone palm tree still standing roughly where Baldwin’s patio table used to be, an orange tree here and there, and a few surviving ancient olive trees that were a hundred or more years old, and which, as I had just then heard, ere supposed to be under the protection of the French government.

Three years after his first visit to the site, this time Caz offered to break down a side door that was nailed shut, so that we could enter and take more photos of the interior of Baldwin’s last room. I wanted to do it, but I told him otherwise, sadly aware that we could likely get away with photographing the structure for the purposes of research, but not with having caused “damage” to it. We had spent the week before documenting Baldwin’s archive, then stored at the house of Leonore, Jill’s daughter, in the tiny Alpine village of Guillaumes, about two hours from St. Paul-de-Vence. Having documented the riches of his library, David’s many paintings, the writer’s photos and posters, we found the visit to the house sad, even disturbing. The boxes whose contents I had photographed painstakingly, and some items stored at Jill’s house, including the famous welcome table, were then the sole material effects of the writer’s domestic life. As we were leaving, I had the feeling that this was my last pilgrimage to the site of Baldwin’s domicile. I picked up as a keepsake a small shard of what might have been a brown clay flowerpot from the dirt where his study used to be.

Most of the physical topography of Baldwin’s intimate house has been lost forever—there are few preserved images from the time he lived there and the site remains unmarked. Like me, many readers and scholars have visited St. Paul-de-Vence in hopes of glimpsing the structure that housed the famous writer. These trips come about because those who read and study this complex writer crave material reminders of his life, especially given that so few of them are present in the United States. We, the privileged few who have managed to travel to Chez Baldwin, have craved tangible connections with the surroundings that fed the author’s imagination and framed his late years.

As Quentin Miller writes in the first issue of the James Baldwin Review, “I have read all of his books to the point that I’ve had to tape the bindings together, but I wanted something else, something that came from being where he had been.” Writing in the Times Literary Supplement about a visit to the site that involved vaulting over a fence, Doug Field expresses dismay at the state of Baldwin’s study, while populating the space with imagined stuff: “photographs and personal, homely objects: a painting by his old friend Beauford Delaney; an exhausted looking typewriter; a drink. . . ; cigarette packets; and a sheaf of papers—a manuscript—but which?”

In 2014, the poet and critic Ed Pavlić had gone to see the house with Lynn Scott and her husband days before my journey here, and he sent me a photograph that helped me to find my way onto the grounds without serious acrobatics. Pavlić’s reaction to the state of Chez Baldwin was more upbeat than mine or Doug’s, as he thought the house sturdy and solid and simply needing “lots of love.” The house of James Baldwin, whether still standing or not, and regardless of its legal ownership, remains an important access point—literal and literary—to Baldwin’s legacy.

An upstairs bedroom window with vines, 2014. Photo by Magdalena J. Zaborowska.

An upstairs bedroom window with vines, 2014. Photo by Magdalena J. Zaborowska.

After my three visits to the site and obsessive rereading of Baldwin’s house-tour narrative in Architectural Digest, I realized that the only way to deal with the material on hand was to attempt to excavate, if you will, what remains of Chez Baldwin despite its gradual erasure, to write into being its material and metaphorical stories as a black queer domestic space that was key to the writer’s later works.

As Toni Morrison claims in the essay “The Site of Memory,” writing is a form of “literary archeology,” where memory, imagination, and language come together to create continuities in black lives past and present: “On the basis of some information and a little bit of guesswork you journey to a site to see what remains were left behind and to reconstruct the world that these remains imply. What makes it fiction is the nature of the imaginative act: my reliance on the image—on the remains—in addition to recollection, to yield up a kind of truth. By ‘image,’ . . . I simply mean ‘picture’ and the feelings that accompany the picture.” Morrison emphasizes that, in contrast, the traditional task of a “trustworthy” literary critic or biographer is to trace the “events of fiction” to some “publically verifiable fact,” to excavate the “credibility of the sources of the imagination, not the nature of the imagination.”

Given my dual tasks of writing a story of my visits to James Baldwin’s house and arguing for literature and architecture as inseparable bedfellows in my reading of the house as a transnational, black queer, domestic space, my goal in these concluding lines falls somewhere in between the two approaches Morrison has delineated. Although as a critic and biographer, I appear to be merely a collector of “publically verifiable fact[s],” I insist on the right to claim access to “pictures” and “feelings” inspired by the onsite research of Baldwin’s house and close readings of his works. As Trinh T. Minh-ha reminds us, “Writers of color. . . are condemned to write only autobiographical works. Living in a double exile—far from the native land and far from the mother tongue—they are thought to write by memory and to depend to a large extent on hearsay. . . The autobiography can thus be said to be an abode in which. . . [they] take refuge.”

While Baldwin fits this description to some degree as a writer rendered homeless by his identity, he also expands it by demonstrating that building one’s abode in language through writing goes hand in hand with establishing domestic spaces, however temporary, that can accommodate a rare and unique subject, a black queer American who has chosen to dwell in the world. It is a great loss that his house in St. Paul-de-Vence can serve as such a space only symbolically, and now only as a memory and an elusive, fragmentary reminder of things past.

__________________________________

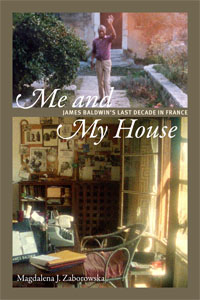

From Me and My House: James Baldwin’s Last Decade in France. Used with permission of Duke University Press. Copyright © 2018 by Magdalena J. Zaborowska.

Magdalena J. Zaborowska

Magdalena J. Zaborowska is Professor of Afroamerican and American Studies and the John Rich Faculty Fellow at the Institute for the Humanities at the University of Michigan, and the author and coeditor of several books, including James Baldwin's Turkish Decade: Erotics of Exile and Me and My House: James Baldwin's Last Decade in France, both published by Duke University Press, and How We Found America: Reading Gender through East European Immigrant Narratives.