Taking a long view of the history of counterfeit items coming to auction, one rises to the top of my mind. The year, 1901. An administrator at the Kunsthistorisches Museum commissions several hapless students from the University of Vienna to create replicas of ten Bruegel paintings and sketches. Over the years, he replaces the authentic works in his museum with the copies. By the time that the museum discovers the deception, ten great objects of antiquity are long-lost.

Throughout the twentieth century, rumors of sightings float through the art world, stories really. Then, in 1981, a print of The Beekeepers in pen and ink comes up for sale at the Lempertz auction. The anonymous seller claims it is one of the recovered Bruegel ten. The auction house brings in an authenticator conversant with Bruegel’s style, who determines that The Beekeepers is, in fact, another counterfeit.

Today, Moses Quimby isn’t convinced that the Plath notebooks are authentic, either. He thumbs his mustache as we walk. Halls branch from the lobby of St. Ambrose to offices and a library and two small galleries. If such an item as the original handwritten draft of The Bell Jar truly exists, why would it reside in a lockbox in an attic in South Boston?

“You know these sorts of counterfeits come up all the time.”

“I have no reason to believe the manuscript isn’t legitimate,” I say.

This is not entirely true, though. A cursory archival search shows no record of Sylvia Plath writing The Bell Jar in three notebooks. Nor is there an account of a handwritten draft of The Bell Jar in Sylvia Plath’s personal journals.

Quimby is half-distracted, looking at his phone and clicking through his messages. I need to fill him in because I only have the notebooks for three days before the Dyce brothers take the items to Sotheby’s.

“The Dyce brothers? The guys with those stupid real estate commercials?” Quimby wants to know if they are as wormy in person as they are in their advertisements.

“If it is real, it would be an unprecedented addition to our twentieth-century slate,” I say.

“The Bell Jar.” Quimby says this with distaste, and I wonder how much of Sylvia Plath Quimby has read. Though I don’t remember exactly when I read The Bell Jar, I am hard-pressed to recall a time when I have not known the story of Esther Greenwood dreaming of becoming a writer, struggling with identity and norms in a mental hospital after spending a manic summer in New York City. “Even if it is real, I just can’t see how it’s relevant for our audience.”

Relevant? For master curators, an object’s relevance is irrelevant. Has the struggle to selfhood ever disappeared? Has our human tendency to focus on our personal inadequacies ever gone out of vogue? Have the blades of Plath’s words gone dull over the decades, or do they still draw blood? Not long ago, Quimby and I would not have been having this conversation. Midfifties with graying temples, Quimby styles himself in suits and ties and with dignity and a touch of smugness. He comes from money, and marketing, and an expensive business school. Last year, when a painting of characters from South Park sold for ten million dollars at Christie’s, Quimby grew convinced that St. Ambrose was missing out on a huge market potential. Impulsively, he refocused St. Ambrose’s offerings to the buying power of millennials, a generation he knows nothing about. Then again, neither do I.

Enter Scarlett: twenty-two, long drape of dark hair, pencil skirts, perfume seemingly curated to imprint on Quimby’s olfactory stimuli, and who, before Quimby installed her as St. Ambrose’s first online sales director, modeled luxury handbags on Newbury Street. Thanks to Scarlett, suddenly St. Ambrose caters to rich young buyers in hoodies who prefer to bid through our new online portal. St. Ambrose has moved away from its standard slates, opting instead for lithographs by Christo, Banksy stunts, and Xerox prints that Scarlett calls “irony art”—as if Scarlett knows the definition of the word “irony.” Meanwhile, Quimby, naturally contrarian, has found in Scarlett an audience and validation.

We step into the elevator together, and as the doors slide shut, Quimby looks at me with a bogus display of warmth. Bogus, because he’s not a warm man. But the silence and sudden close quarters of an elevator bring about an uncomfortable intimacy. “Is Istanbul still the top contender?” he asks, moving away from the subject of The Bell Jar. Braving my retirement among the cities where I curated in the early years of my profession continues to have its special appeal. I have many options to choose from, among them Paris, Berlin, St. Petersburg, and Madrid. I’ve recently added Beirut and Cape Town to the catalog of possibilities. “Yes, Cape Town is lovely,” he says. To be clear, until very recently, retirement was not a consideration I visited in earnest. Yet, an idea, like a celestial body, eventually takes on its own atmosphere and weight. More and more, I feel that I both belong among the antiquities at St. Ambrose and that I do not. “You should consider Buenos Aires. Trust me. Europe is like stale coffee. Buenos Aires has the Malba. And the beaches. You’d do well there.”

“Buenos Aires, all right,” I say, remembering how, in The Bell Jar, Esther Greenwood puts up with eccentric men, men with interesting names like Socrates and Attilla, rich intellects and boys from famous families who play tennis and are perfectly tan but are also too short or too ugly or too bald. Though she hates the idea of serving these men, Esther Greenwood laughs at their jokes and acts polite. So I will capitulate, and I will engage Moses Quimby in small talk if it makes him feel better, because I know, like all master curators know, like Esther Greenwood knows, that sometimes giving someone what they want is the only move we have in this game of listening and pivoting and dancing.

In the lower level of St. Ambrose, Quimby and I walk a short passageway lined on both sides with doors. I stop at the room marked safe holdings, dial a code into a keypad on the wall, and yank on a handle. Inside, I unlock one of the wooden file cabinets and bring out the lockbox. At the table, Quimby scrutinizes the three notebooks. The pages make the sound of dry leaves crackling as he turns them. “Times are changing, Estee. Nobody’s interested in buying the personal library of Charles Dickens or thirteenth-century paleographic texts. The public market desires pieces it can connect with. People want local now. An artist’s province matters as much as an object’s provenance.”

“Sylvia Plath was from Massachusetts,” I say.

“You know what I’m saying. Nobody’s bidding on literary incunables. People are looking for timely. There’s nothing timely about Sylvia Plath.”

I have learned over the years that as difficult as it is to argue with Quimby, it is even more difficult to bring an argument to him. I continue to try, nonetheless. “Mr. Quimby, if this is a genuine work of Sylvia Plath’s, who better to sell it than us?”

“It’s not worth taking it on, even if it is genuine. What’ll it fetch? A couple thousand? The authentication costs alone will eat up our profit.”

“If it is authentic, I can’t imagine St. Ambrose letting this go to another house, can you?”

Quimby peels off his white cotton glove and sighs.

“Here’s what I’m gonna do. First, I’ll let you carry out your due diligence. Meanwhile, I’ll perform mine.”

By that, I know Quimby means he will ask Scarlett about the generational appeal of The Bell Jar and of Sylvia Plath. He has no ability to judge his instincts anymore. If I can prove the notebooks are Sylvia Plath’s, and Quimby is satisfied with their relevance to modern buyers, then he’ll consider—consider—adding the objects to the upcoming slate.

About that phony Bruegel sketch: several months after the Federal Criminal Police are finished with the object, the counterfeit is returned to the Lempertz Auction House and put on display as an artifact of intrigue. At the age of thirty-two at the time, I am curating the special collections for the Berlin city library when I am granted special permission to visit The Beekeepers. In a brightly lit room full of tall windows, I examine the rendering of four hooded men in a field. They are thieving honey from clay hives. Their hands are unprotected from the bees. Their faces are hidden behind basket-woven masks. I find the quality to be most impressive. What a remarkable job the architect of this fake has done! The counterfeiter has gone so far as to re-create the document on parchment from the sixteenth century. Doubt, it seems, is the only quality that gave the object away, for anyone who has followed the story of the Bruegel ten knows it is improbable that, after all this time, one would show up on the open market. That it arrived with no history of where it has been, and no explanation for how it got to auction, continues to elicit more than a little suspicion. Parsimony: the simplest explanation is that it must be a counterfeit.

Though to this very day, I ask myself, what if we all got it wrong? What if the only evidence that the rendering wasn’t real was rational thinking coupled with the belief that it simply had to be a fake?

With the Plath notebooks, I hope to eradicate any such uncertainty by bringing in an expert of my own. Despite my specialty in manuscripts, I require a connoisseur of Sylvia Plath and her work. I open my laptop and start an Internet search, the trailhead of all twenty-first-century journeys. The website of Boston University brings me to a professor of literature named Nicolas Jacob. A thorough look at his papers on Sylvia Plath, his four books on Sylvia Plath, and his graduate dissertation on Sylvia Plath, and I believe I have found my assessor.

Nicolas Jacob is curt over the phone. “You’re with St. Ambrose?”

“Yes—”

“The auction house?”

“Yes, we have a manuscript that falls in line with your area of expertise—”

He cuts me off again. “You’ll have to find somebody else.”

“But—”

“I don’t work with auction houses.”

“Yes, but—”

“As a rule. I’m sorry—”

“You see, I have, or at least I think I have, what might be an original draft, a handwritten original draft, of The Bell Jar.”

This gets his attention.

Nicolas Jacob arrives at St. Ambrose on a late-June morning. He is gingered haired with gold-framed glasses and a face that, by my estimation, is eighty percent beard. His shirt is buttoned to the top, though he wears no tie. His burgundy summer cardigan is missing a button. Standing over the three notebooks in the safe holdings room, Nicolas rubs his hands together, brushing away invisible particles.

Nicolas removes a small case from the pocket of his trousers. He places it on the table and unzips it to reveal a set of tools. Using padded tweezers, he pinches a corner and draws open the green-covered notebook.

My attempts to engage Nicolas result in only clipped answers, in yeses and nos. He does not smile, or maybe he does smile, but the beard disguises his smile, as it hides all of his facial cues beyond those suggesting conscientiousness and low tolerance. “It’s extremely fragile,” he says at one point. This, I already know. With poor temperature and humidity regulation, attics make for abysmal incubators of antiquity. I tell Nicolas about the Dyce brothers, and their probate purchase on Napoleon Street, and their discovery in its attic, and how it is my suspicion that the attic might have been Plath’s at one point in time. “Not possible,” Nicolas says. “If you’d said they found it in a house in Wellesley, Jamaica Plain, or even Winthrop, maybe. But Sylvia was not a Southie.”

Nicolas scratches at his beard. He turns over his leather messenger bag and removes from it a document in a plastic sleeve. I ask him what he’s brought, and for the first time in our short affiliation, Nicolas’s tone changes from prim to a quality I can only describe as slightly more tender.

“It’s a handwritten early poem of Sylvia’s.”

The title, I see, written across the top of the single page reads MISS DRAKE PROCEEDS TO SUPPER.

“I’m ready for that light rig now.”

From the closet I wheel out a table-and-lamp apparatus. Nicolas carries the green-covered notebook and the sleeved document to the lamp and places both under the light with a magnifying glass top.

“If the handwriting in the notebooks is a different style than Sylvia’s normal handwriting, or if the ink hasn’t permeated into the notebook’s paper, the content of the notebook is recent and likely a forgery,” he says. Administering his forensic handwriting evaluation, Nicolas compares an N, a T, and an R from one document to corresponding letters in the other. Another ten minutes pass without a word or signal. Nicolas pushes his fingers through his beard again, his fingertips searching for skin. If he believes it’s authentic, or if he sees a detail that signals it’s just not right, Nicolas is unwilling to say. Or perhaps he cannot say. Perhaps he does not know.

With his phone, he snaps color spectral photos of a page from the notebook. He opens his laptop, and, examining the photo on the screen, separates the words from the background colors.

Nicolas makes a small noise. He pushes his glasses up the bridge of his nose, then asks me if the Dyce brothers indicated who they bought the house from. The address was in foreclosure and purchased from a bank, I say. He thinks a minute. “All right, we can check with the housing records.”

“It’s authentic, then?”

Nicolas straightens his spine. Blinks. Nods.

“One of the great pleasures of my life in academia is having had the honor of seeing pieces of Sylvia’s work before. Letters, notes, pages of poetry. But nothing this complete. Was there anything else the Dyce brothers found with the notebooks? Other items, like a letter that might explain how the manuscript got here?”

None, I say. I gather the green-covered notebook, take up the other two from the table, and place all of them back into the lockbox.

“A manuscript like this doesn’t just fall into your lap,” he says. “As far as we know, it’s the only handwritten version of Sylvia’s novel in existence. It deserves to be evaluated and studied.” Nicolas rises from his stool and follows me to the cabinet drawer as I place the lockbox back inside. “Aren’t you the least bit curious? How is it no one knows this version of the manuscript exists?”

Yes, I have questions, but there will be time for seeking answers. For now, there is much to do, and I am focused on relaying the good news to Quimby, focused on reaching the Dyce brothers before Elton and Jay Jay decide to bring the notebooks to another auction house, and focused on the one thing I do know, the one thing that matters. After fifty-five years, Sylvia Plath has returned.

____________________________________

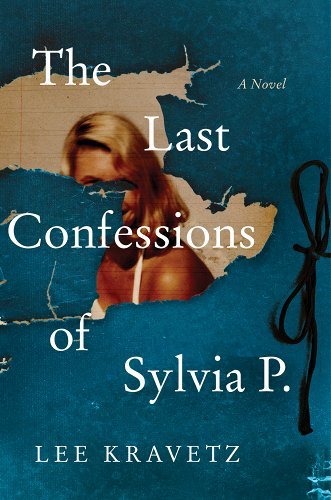

From the book: The Last Confessions of Sylvia P. by Lee Kravetz. Copyright © 2021 by Lee Kravetz. Reprinted courtesy of Harper Books, an imprint of HarperCollins Publishers