The Isolation of Being Deaf in Prison

Jeremy Woody on Life in the State Prison, as Told to Christie Thompson

As told to Christie Thompson

When I was in state prison in Georgia in 2013, I heard about a class called Motivation for Change. I think it had to do with changing your mindset. I’m not actually sure, though, because I was never able to take it. On the first day, the classroom was full, and the teacher was asking everybody’s name. When my turn came, I had to write my name on a piece of paper and give it to a guy to speak it for me. The teacher wrote me a message on a piece of paper: “Are you deaf?”

“Yes, I’m deaf,” I said.

Then she told me to leave the room. I waited outside for a few minutes, and the teacher came out and said, “Sorry, the class is not open to deaf individuals. Go back to the dorm.”

I was infuriated. I asked several other deaf guys in the prison about it, and they said the same thing happened to them. From that point forward, I started filing grievances. They kept denying them, of course. Every other class—the basic computer class, vocational training, a reentry program—I would get there, they would realize I was deaf, and they would kick me out. It felt like every time I asked for a service, they were like, “Fuck you, no, you can’t have that.” I was just asking for basic needs; I didn’t have a way to communicate. And they basically just flipped me the bird.

While I was in prison they had no American Sign Language (ASL) interpreters. None of the staff knew sign language, not the doctors or the nurses, the mental health department, the administration, the chaplain, the mailroom. Nobody. In the barbershop, in the chow hall, I couldn’t communicate with the other inmates. When I was assaulted, I couldn’t use the phone to call the Prison Rape Elimination Act (a federal law meant to prevent sexual assault in prison) hotline to report what happened. And when they finally sent an interviewer, there was no interpreter. Pretty much everywhere I went, there was no access to ASL. Really, it was deprivation.

I met several other deaf people while I was incarcerated. But we were all in separate dorms. I would have liked to meet with them and sign and catch up. But I was isolated. They housed us sometimes with blind folks, which for me made communication impossible. They couldn’t see my signs or gestures, and I couldn’t hear them. They finally celled me with another deaf inmate for about a year. It was pretty great, to be able to communicate with someone. But then he got released and they put me with another blind person.

It’s hard to describe the fury and anger.

When I met with the prison doctor, I explained that I needed a sign language interpreter during the appointment. They told me no, we’d have to write back and forth. The doctor asked me to read his lips. But when I encounter a new person, I can’t really read their lips. And I don’t have a high literacy level, so it’s pretty difficult for me to write in English. I mean, my language is ASL. That’s how I communicate on a daily basis. Because I had no way to explain what was going on, I stopped going to the doctor.

My health got worse. I came to find out later that I had cancer. When I went to the hospital to have it removed, the doctor did bring an interpreter and they explained everything in sign language. I didn’t understand, why couldn’t the prison have done that in the first place? When I got back to prison, I had a lot of questions about the medicines I was supposed to take. But I couldn’t ask anyone.

I did request mental health services. A counselor named Julie was very nice and tried her best to tell the warden I needed a sign language interpreter. The warden said no. They wanted to use one of the hearing inmates in the facility who used to be an interpreter because he grew up in a home with deaf parents. But Julie felt that was inappropriate, because of privacy concerns. Sometimes we would try to use Video Remote Interpreting, but the screen often froze. So I was usually stuck having to write my feelings down on paper. I didn’t have time to process my emotions. I just couldn’t get it across. Writing all that down takes an exorbitant amount of time: I’d be in there for thirty minutes, and I didn’t have the time to write everything I wanted to. Julie wound up learning some sign language. But it just wasn’t enough.

My communication problems in prison caused a lot of issues with guards, too. One time, I was sleeping and I didn’t see it was time to go to chow. I went to the guard and said, “Hey, man, you never told me it was chow time.” I was writing back and forth to the guard, and he said he can’t write because it’s considered personal communication, and it was against prison policy for guards to have a personal relationship with inmates. That happened several times. I would have to be careful writing notes to officers, too, because it looked to the hearing inmates like I was snitching.

Once they brought me to disciplinary court, but they had me in shackles behind my back, so I had no way to communicate. Two of the corrections officers in the room were speaking to me. All I saw were lips moving. I saw laughter. One of the guards was actually a pretty nice guy, one of the ones who were willing to write things down for us deaf folks. He tried to get them to take the cuffs off me. He wrote, Guilty or not guilty? But the others would not uncuff me. I wanted to write not guilty. I wanted to ask for an interpreter. But I couldn’t. They said, “Okay, you have nothing to say? Guilty.” That infuriated me. I started to scream. That was really all that I could do. They sent me to the hole, and I cried endlessly. It’s hard to describe the fury and anger.

Prison is a dangerous place for everyone, but that’s especially true for deaf folks.

Woody spoke to the Marshall Project through an American Sign Language interpreter. The Georgia Department of Corrections did not respond to a request for comment concerning allegations in this interview.

__________________________________

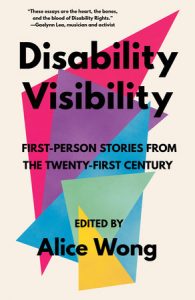

From Disability Visibility: First-Person Stories from the 21st Century edited by Alice Wong. Reprinted by permission of Vintage Books, an imprint of the Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House LLC.

Jeremy Woody

Jeremy Woody is a contributor to Disability Visibility: First-Person Stories from the 21st Century edited by Alice Wong. He is currently suing Georgia corrections officials over his treatment in Central State Prison in Georgia, with the help of the American Civil Liberties Union’s Disability Rights Program and the ACLU of Georgia. He lives near Atlanta.