The Ironic Twist of Age: What It’s Like to Keep Writing at 91

Hilma Wolitzer on Finding Creative Drive Later in Life

When I was younger and someone asked what the best thing was about being a writer, I had a ready, two-part answer. The first—that I could go to work in my pajamas—was a bit facetious, and the second—that I got to live other lives through my characters—was sincere, but also borrowed (or stolen) from Anne Tyler.

Looking back, I realize that the truly best thing about being a young (well, middle-aged) writer was the lovely, easy flow—the gush, often—of language, the way words and phrases seemed to find me, sometimes at odd times and places. If I was in bed when inspiration struck, and had a pen or pencil nearby, I would scribble on the margin of a newspaper or in my date book. Crossing the street, I’d write on the palm of my hand. But if I was in the shower or somewhere else without a writing implement, I could depend on memory most of the time. Whole paragraphs, pages, even chapters!—were safely retained in my head until I was able to write them down. I once heard John Irving refer to this phenomenon as “the enema syndrome.”

Elderly now, I find that language can be elusive, and not just when I’m trying to write. Like many people my age, I seem to lose a noun or two every day lately. They’re like buttons that have fallen off my shirt and rolled under the bed, and I can’t bend down to retrieve them. I can no longer count on my famous short-term memory either. Recent events can seem as ephemeral as dreams. And those jokes that I used to find so amusing about old people and forgetfulness—“Rose, what do you call that flower with thorns?”—aren’t quite as hilarious these days. Anyone who claims that age is “just a number” is either very young or works for Hallmark.

Senior discounts and a seat on the bus don’t begin to compensate for the losses—of one’s faculties, mobility, robust health and, most especially, of loved ones. In his seminal poem “The Old Fools,” Philip Larkin asks (not unreasonably) “Why aren’t they screaming?” Well, maybe some of us are (if only privately, or even silently), while others are still so deeply entrenched in life that we momentarily forget our infirmities or that “Extinction’s Alp,” as Larkin observes “is rising ground” for us.

If Joyce Maynard could look back with nostalgia at 18, I can look forward with anticipation at 91.

Of course we’re replaceable, in the natural order of things. Newer, younger writers keep coming up like chorus girls. But long-lived writers have one obvious advantage over the wunderkinds: more experience of the world. After all, we contain multitudes—those decades from infancy to advanced age—ergo: lots of literary material. But I wrote a haiku a couple of years ago that addresses a predictable dichotomy.

That ironic twist

Of age: knowing far more than

You can remember.

At least there’s one loss I haven’t suffered in my dotage—that voracious curiosity about what’s going to happen next—in this beautiful, terrible world, and on the page. It’s the reason I read and the reason I write. And it’s why I’m still glad to wake up each morning. If Joyce Maynard could look back with nostalgia at 18, I can look forward with anticipation at 91.

So many writers who were productive in their later years have set a sterling example. Philip Roth formally retired from writing in 2012, as he approached 80, but he was particularly prolific in the decade before that. In her nineties now, Cynthia Ozick’s fierce intelligence is still on display. And despite the somber title of Diana Athill’s memoir, Somewhere Towards the End, written when she was 89, her tone is positive and exuberant. “Because after all, minuscule though every individual, every ‘self’ is, he/she/it is an object through which life is expressed, and leaves some sort of contribution to the world.”

Yet in recent years a little panic starts to set in as I sit at my desk. What if I have nothing else to say? Or what if I can’t think of the right words, the way that happens in conversations with friends? I’m on my own now. My husband Morty, that human thesaurus, who used to help me fill in the blanks—in creative and social situations—died of Covid-19 last year.

Then I remember that other question people are always asking writers: “Where do you get your ideas?” I have a handy and honest answer to that one—my fiction has never been jumpstarted by an idea. I always conjure up the characters first, and they tell me their ideas. So I start to relax, waiting for that faithful company to shuffle in and whisper their stories in my ear.

__________________________________

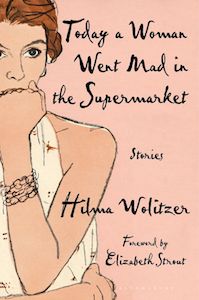

Today a Woman Went Mad in the Supermarket is available from Bloomsbury Publishing. Copyright © 2021 by Hilma Wolitzer.

Hilma Wolitzer

Hilma Wolitzer is a recipient of Guggenheim and National Endowment for the Arts fellowships, an American Academy of Arts and Letters Award in Literature, and a Barnes & Noble Writers for Writers Award. She has taught at the Iowa Writers’ Workshop, New York University, Columbia University, and the Bread Loaf Writers’ Conference.